The fight against inflation

Inflation has reached unprecedented levels around the world over the last two years. How does the science of economics explain this phenomenon? Can it help reduce price increases? Is there consensus about it?

Investigative report by Nicolas Sandanassamy - Published on , updated on

The worst inflation in 30 years

Europe has enjoyed stable prices for over three decades, with a steady but low increase of 2% per year.

But prices for shopping, filling the tank, lighting, and heating have been rising since 2021. For example, according to INSEE in France, the price of meat increased by 11% in one year, reaching even 30% for frozen meat. The price of fresh vegetables has increased by 18% and pasta by 20%. A general and uninterrupted increase in the prices of goods and services over several quarters is called ‘inflation’. Inflation in France and the rest of Europe was triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns. It surged again in February 2022, due to the outbreak of Russia’s war against Ukraine and the resulting pressure on oil and gas supplies. Current inflation rates – close to 6% in France and 9% among its neighbours – is mainly the result of soaring energy prices: up 23.1% in 2022 after an increase of 10.5% in 2021. This has affected production costs, raw material supplies, and as a result, many everyday consumer products. France suffers least from the impact of electricity on inflation in Europe, due to its nuclear fleet that makes it less dependent on fossil fuels. The government has also contained price increases with several support measures including price caps. But will current inflation rates continue? Are there economic tools to push it down?

The many faces of inflation

Venezuela 234%, Argentina 95%, Great Britain 11%, United States 6.5%, and France 5%: inflation rates vary around the world in 2022, as do the root causes. Like the rest of Europe, France was accustomed to “low” inflation at around 2% for 30 years. But in 2021, prices began to rise moderately between 2% and 5%, then shot up to between 5% and 10%. Venezuela and Argentina suffer from hyperinflation at rates of several hundred percent per year, even reaching several thousand. Such levels of inflation can cause monetary systems and national currencies to collapse, leading to social crisis and political instability.

The causes of inflation are multiple and correlated.

Are the causes of inflation always the same? According to economists, several phenomena can contribute to inflation, with cumulated effects in some cases.

One of the main factors is rising production costs. To compensate for the increase in the cost of raw materials, energy (gas, oil, etc.), and certain components like semiconductors, companies increase their prices, causing a first inflationary hike. Rising prices can increase wages, generating another rise in prices. A wage-price spiral can then take hold - like in Germany in the 1920s after the First World War, or in Zimbabwe recently. When raw materials or energy are shipped from abroad, it’s called “imported inflation,” but the mechanism is the same.

Inflation can also be generated by demand exceeding supply. Prices then mechanically increase to rebalance each other. Increase in demand, on the other hand, can be due to increases in wages, credit, government spending, or external demand. Supply can also be affected by a shortage of raw materials, energy, or skilled labour – as was the case in France recently with a shortage of building materials.

Finally, some “monetarist” economists believe that inflation is also the result of too much money in circulation compared to the quantity of goods and services available on the market.

A price spike driven by energy costs

Europe’s current inflation is mainly due to soaring energy and raw material prices and high dependency on imported hydrocarbons. Prices are therefore likely to remain high while the Russia-Ukraine conflict persists. The ecological transition also requires massive investment. That said, France has managed to avoid the worst. Measures to support businesses (loans, partial activity schemes, etc.) and bolster household purchasing power (special allowances, price caps, etc.), and nuclear power have helped to contain inflation at around 6%, compared with 10% for the rest of Europe.

A typical shopping cart to measure inflation

Throughout the year, INSEE monitors the evolution of costs including coffee, pasta, biscuits, meat, clothing, health, tobacco, fuel, and housing expenses considered representative of consumption by French households. The list is updated annually to take into account lifestyle changes. This shopping cart is used to measure inflation each month, presented as a consumer price index (CPI). Eurostat uses another index, the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) to compare inflation rates in the euro area and European Union.

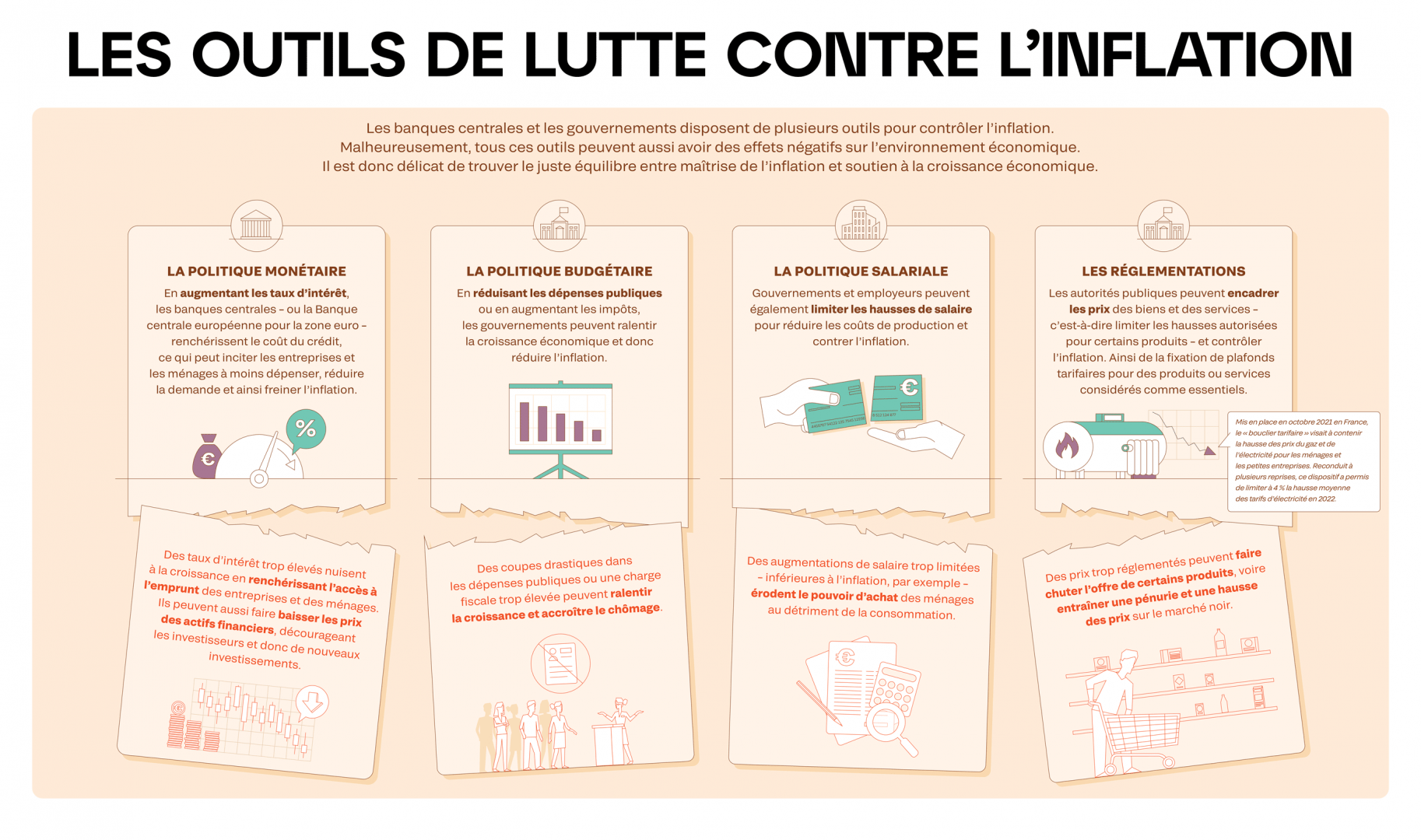

Anti-inflation tools

Monetary policy

By raising interest rates, central banks – the European Central Bank for the euro area – increase the cost of credit, encouraging companies and households to spend less, in turn reducing demand and curbing inflation.

But excessively high interest rates slow growth by making borrowing more expensive for businesses and households. They can also drive down the prices of financial assets, discouraging investors and new investments.

Budgetary policy

Governments can slow economic growth by cutting public spending or raising taxes which reduces inflation.

But such drastic cuts in public spending or an excessive tax burden can slow growth and increase unemployment.

Wage policy

Governments and employers can also limit wage increases to reduce production costs and counter inflation.

But if wage increases are too low – for example below inflation – household purchasing power drops, reducing consumption.

Regulations

Public authorities can regulate the prices of goods and services by limiting authorised increases for certain products to control inflation. Fixing price caps for products or services is considered essential.

Price caps were applied in France in October 2021 to contain the increase in gas and electricity prices for households and small businesses. Repeatedly updated, this measure limited the average increase in electricity rates to 4% in 2022.

But overregulating prices can cause supply of certain products to fall, even leading to shortages and increases in black market prices.

The limits of modelling due to an unpredictable future

Economic models used to forecast inflation project short – and long-term trends.

They are based on historical data, indexes like consumer prices, import prices, wages and assumptions about events that may affect prices, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, wars, and geopolitical tensions. Central banks and governments use these projections to guide their decisions about controlling inflation. However, uncertainties undermine these forecasts: how long the Russia-Ukraine war will last, developments in oil and gas prices, and for France, when certain nuclear power plants will be back in service. As a result, the Banque de France presented several hypotheses in its June 2022 macroeconomic projections, including annual inflation at 5.6%. This scenario, based on a total ban on Russian coal applicable on 10 August 2022, was judged most likely. But 2022 inflation rates in France were lower, reaching only 5.2%. INSEE’s projected inflation rate of 6.6% in December was not more accurate, with price increases reaching only 5.9% in the last month of 2022. INSEE estimated that energy prices would continue to rise but they declined. Their predictions were not accurate, showing how difficult it is to make accurate forecasts, even just one month ahead.

The ECB and interest rates: one of many tools

The European Central Bank (ECB) raised interest rates in February for the fifth time in less than a year. This monetary policy decision aimed at controlling inflation has been plaguing Europe for over a year. The ECB raises rates when inflation becomes too high to increase the cost of ‘renting’ money. The aim is to discourage borrowing, reducing the circulation of money and consumption to ultimately stop the inflation spiral.

Analysing inflation is controversial.

There is more to an economist’s job than calculations when it comes to analysing the causes of inflation or predicting financial crises.

Economics is at the crossroads of several disciplines including mathematics, sociology, psychology, history, and political science. Theoretical models are developed and put to stringent but empirical tests to explain economic and social phenomena. As a result, economists’ visions about how the economy functions and the role of public authorities diverge. For example Keynesian economists believe the market cannot self-regulate alone to eliminate economic imbalances which can lead to unemployment and low growth. They therefore advocate government intervention by increasing public spending or reducing taxes to boost activity, even if it results in a temporary budget deficit. In contrast, monetarist economists following in Milton Friedman’s footsteps argue that the amount of money in circulation is the main cause of economic fluctuations, especially inflation. They believe the market is capable of self-regulating, arguing for predictable – even restrictive – monetary policy aimed at maintaining stable and moderate growth in money supply and limited government intervention.