The ocean: the new mining eldorado?

Exploration missions in search of highly coveted minerals are currently multiplying. But the technical, economic and environmental challenges are formidable … and perhaps insurmountable!

Investigation by Isabelle Bellin - Published on

More minerals underwater than on land

In January 2024, Norwegian MPs voted in favour of prospecting for seabed minerals over a wide section of the continental shelf where the country has sovereign rights. A step towards the first global operation? In any event, this decision is being closely followed by a number of countries that are also considering scraping the abyssal plains or drilling into mid-ocean ridges and mounts.

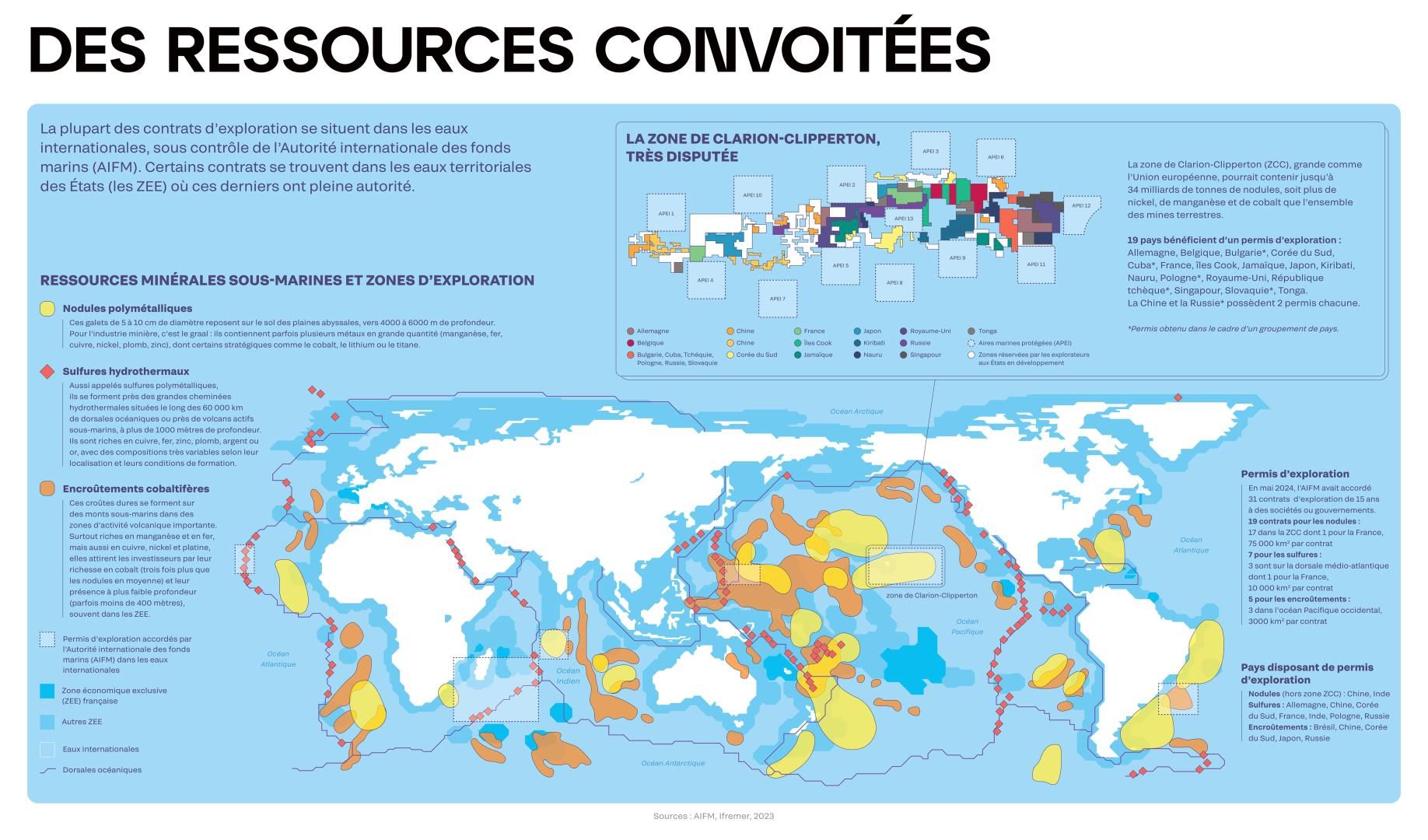

What are they coveting? Metals, for which there is an increasing demand, in order to power multiple digital and energy technologies, notably meeting the massive demand for batteries. But the deep seas sometimes contain larger amounts of resources than are found on land: there are great quantities of manganese, copper, cobalt and nickel, and China is one of the global leaders in the industrial transformation of a number of these minerals.

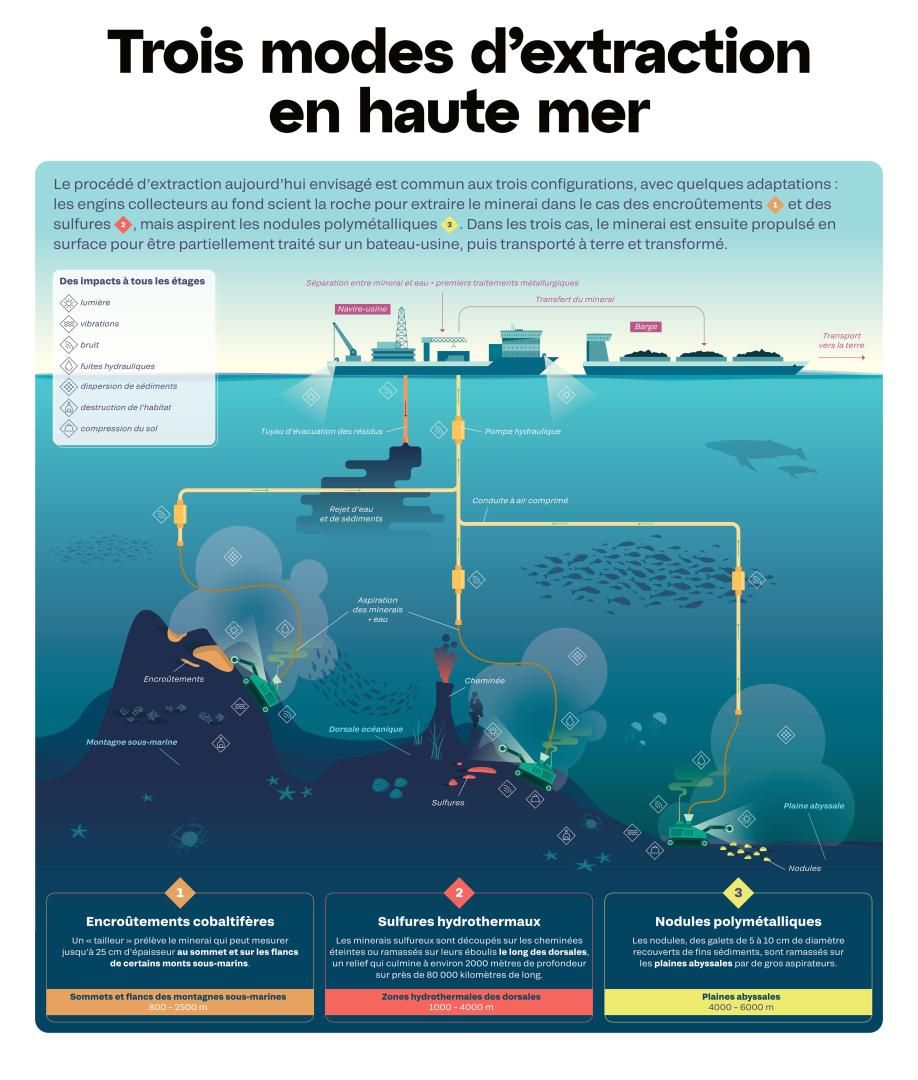

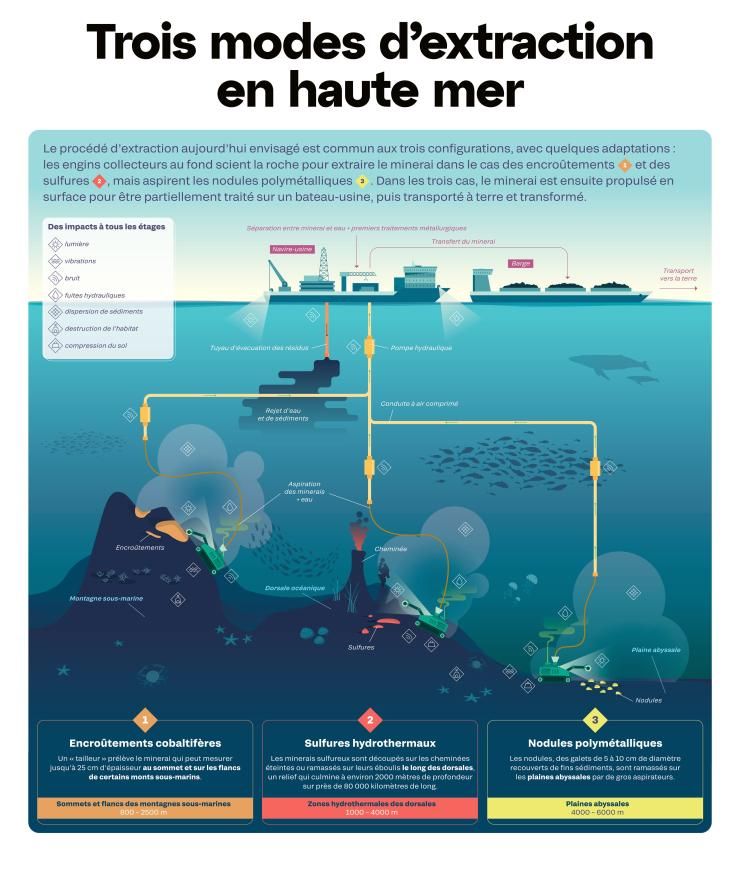

There are three forms of such minerals, which take thousands, even millions of years to solidify from metals present in seawater or that spurt from the oceanic crust. The most abundant – hundreds of billions of tonnes – and most coveted are the nodules that cover immense abyssal plains at depths of 4,000–5,000 metres. They are host to a biodiversity that is all the richer for their high density on the ground. Across radii averaging 50 km, sulphides carpet hydrothermal fields on the edge of tectonic plates, sometimes at a depth of 800 metres. Lastly, cobalt-rich crusts cover certain seamounts, sometimes at depths of 400 metres and across thousands of square kilometres.

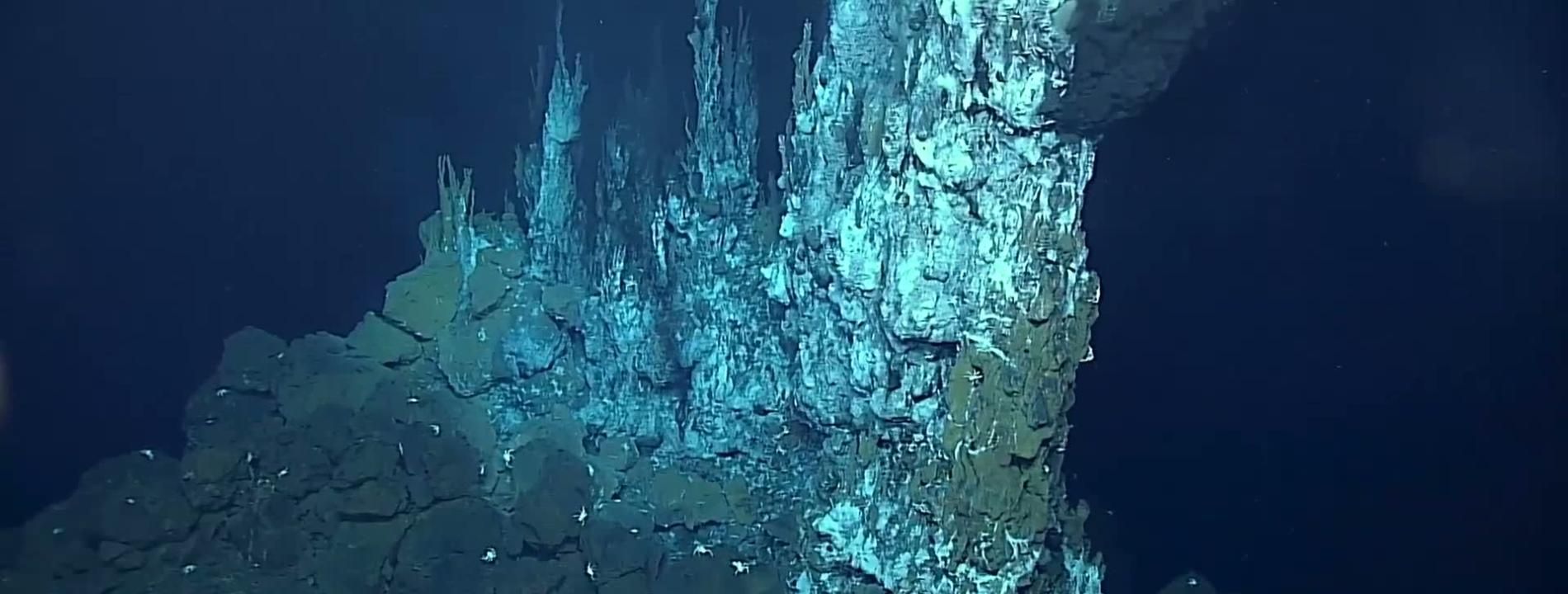

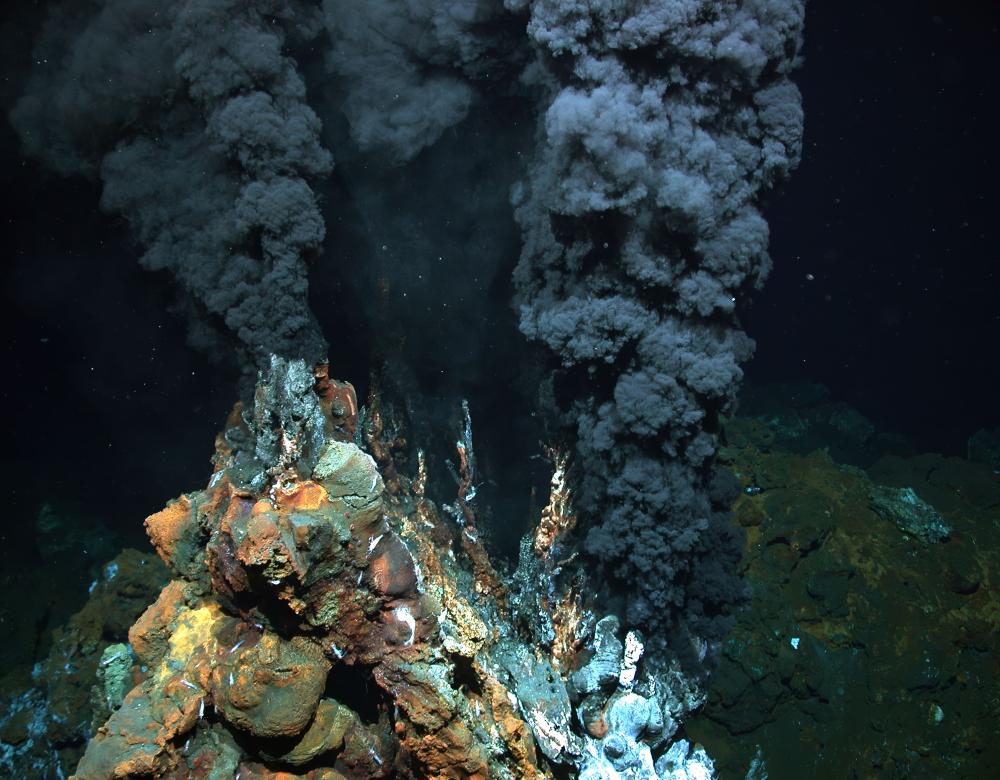

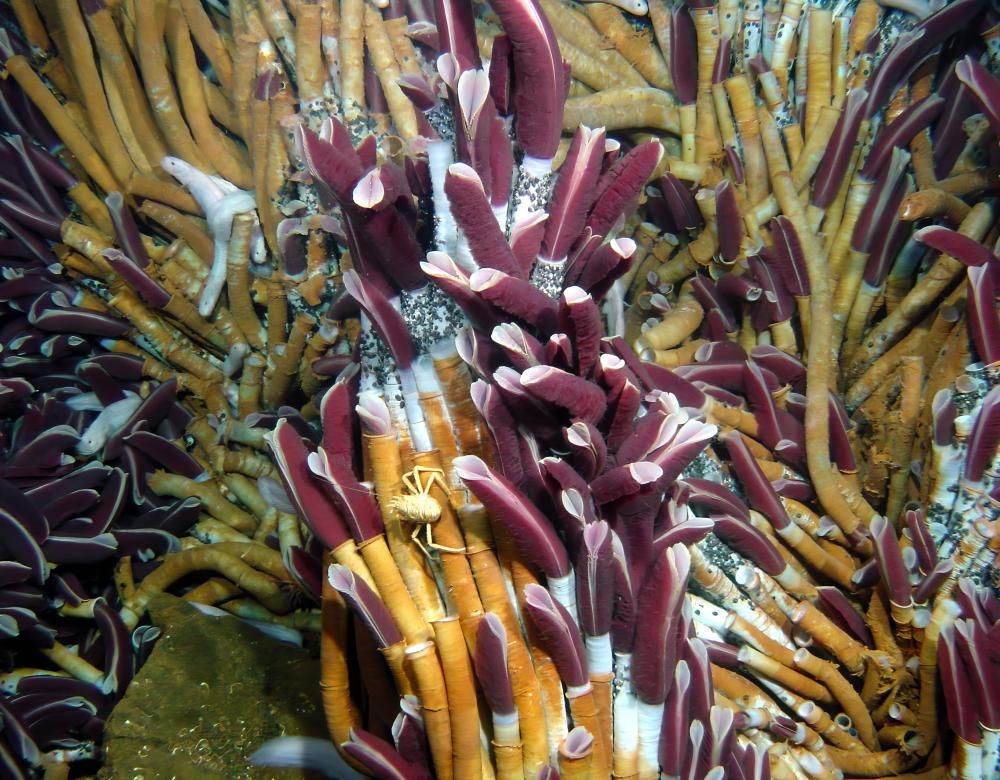

Vents rich in metals

Discovered in the Pacific Ocean in the 1970s, incredible hydrothermal springs spit out burning fluids from the bowels of the Earth, at around 400 °C. They are located along the mid-ocean ridges, long chains of seamounts. Upon contact with cold water, the emitted fluids solidify, forming vents that are tens of metres high. They are composed of a number of dissolved chemical elements and polymetallic particles. Oceanographic missions have demonstrated that such springs occur on average every 100 km! Rich ecosystems live around such springs (crabs, shrimps, mussels, micro-organisms, etc.), in the darkness of the abyssal depths.

"Humanity’s shared heritage"

Underwater mineral deposits were discovered circa 1860. A century later John Mero, an American geologist, announced the existence of colossal resources in the form of exploitable nodules. Interest rapidly declined in view of the technological challenges and a fall in the price of metals. Nevertheless, to prevent industrialised countries from monopolising such resources, in 1970 the United Nations declared them "Humanity’s shared heritage".

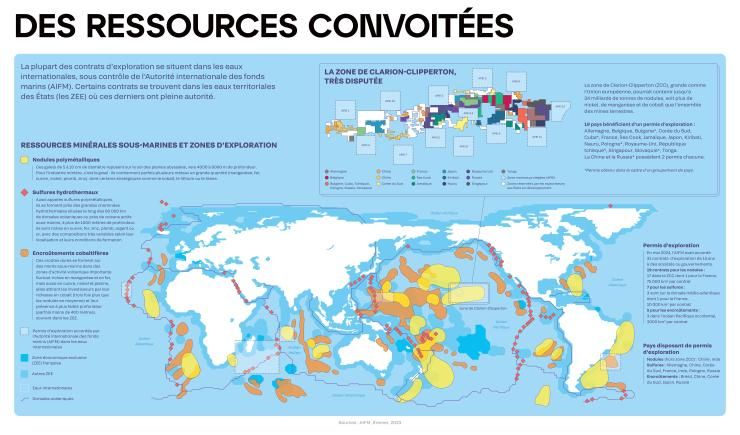

Following this mandate, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) was created in 1994. It is responsible for regulating the exploration and exploitation of the deep sea mineral resources beyond national jurisdictions, and organising the redistribution of such wealth to developing countries and those at risk of being affected by mining. Comprising 168 states, it manages over 50% of the seabed within the "international zone", i.e. the zone that extends beyond the continental shelf (up to a depth of 200 m) and exclusive economic zones (EEZs, that extend as far as 200 nautical miles).

There are around 250 exploitable zones, but no applications will be accepted until an underwater mining code specifying the technological, financial and environmental constraints has been adopted; the latter are now included in the ISA’s prerogatives. The adoption of this code has been postponed to 2025 or later. But loopholes, that certain countries could exploit, still remain. In the meantime, in May 2024 the ISA issued 31 exploration licences involving 21 countries. Indeed some criticise the ambivalence of its functions since in fact this supervisory authority is also dedicated to exploitation.

Ploughing the… abyssal plains

In the mid-Pacific between Hawaii and Mexico, at a depth of around 5,000 metres, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), rich in nodules, is the best-known and most coveted zone, with 19 exploration licences issued out of a global total of 31. The Metals Company (TMC) harvested over 3,000 tonnes from it in late 2022, using a machine designed by Allseas, an offshore oil company capable of recovering 1.3 million tonnes per year. Other competing companies: the Norwegian Loke Marine Minerals and the Belgian Global Sea Mineral Ressources, who carried out a pickup test on the nodules in 2021 without using pumps, which was a delicate and costly operation.

Multiple impacts on the environment

The effects of mining would be comparable to a volcanic eruption; the total area affected would be two to five times greater in the operating area. The most immediate effects are habitat loss and sediment plumes, washed hundreds of kilometres away, and the burial or death of bivalves, soft and black corals and other filter-feeding animals. In the longer term, its impact would also be significant: a study carried out in 2023 showed that half the fish and shrimps had disappeared from an area exploited for 2 hours, and this was carried out a year after the test!

The water column (between the surface and the ocean floor) could also be affected by the release of fluids, and fishing could be affected. Added to which is the noise associated with mining machinery, ships, pumps and traffic; and associated pollution and light. And ultimately, what happens to the carbon assimilated by the fauna then sequestered on the seabed – the natural "carbon sink" – since its effects on the climate are as yet unknown?

According to Ifremer (the French sea exploitation research centre), it may take years, if not centuries, to restore a site’s surface sediments! Hence, 26 years after an extraction test carried out within the Peru basin in 1989, traces of dredging remained visible and biodiversity was reduced. Therefore, mining companies are working on designing machinery that minimises sediment plumes. But researchers warn that, for a proper assessment of the risks, their dispersion models need to be site-specific. Since due to a lack of long-term monitoring, the resilience of marine ecosystems is still not understood.

The challenges of exploration

Devoid of volcanic activity, the areas coveted by industrial companies have rarely been studied. Everything remains to be discovered! Hence, in July 2024, an astonishing release of oxygen by the nodules was observed at a depth of 4 km within the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, in the absence of light and therefore photosynthesis! So prior to any exploitation, an ecosystem inventory is imposed by the ISA. Thus the capacity of deep sea animal species to disperse, reproduce and colonise new sites also forms the subject of research: essential knowledge as regards potential exploitation.

Exceptional biodiversity

In 1976, thick bushes of giant worms were discovered near hydrothermal springs, surrounded by beds of enormous mussels, anemones, crabs, shrimps, etc. A rich ecosystem in which, without light and with very little oxygen, such animals feed on bacteria that derive their energy from the hydrogen sulphide emitted through the vents. But due to lack of resources, less than 2 % of species are listed, in a seabed that is 80 % unexplored. However biodiversity on the ocean floor could be three times higher than in the water column: genuine oases containing up to 200 species of invertebrates within a surface area the size of a sheet of A4.

Is such exploitation truly profitable?

In 2019, the Canadian company Nautilus Minerals went bankrupt after having attempted to extract hydrothermal sulphides at a depth of 1,600 metres near the coast of Papua New Guinea. This small, very poor country thought it would be benefiting from a windfall; in fact it inherited heavy debt and environmental damage. In the summer of 2023, the project was relaunched by Deep Sea Mining Finance, the company that had acquired Nautilus Minerals with promises of debt relief.

At least were the project to survive the major financial risks: the variability of metal prices (cobalt was down 10 % between 2016 and 2023, whilst electric vehicle production went up by 2,000 %); the uncertainty over demand (if new battery chemistry is developed); the economic model (from extraction to separation to metallurgy) and ecological standards. In addition, regulatory uncertainty persists: in Europe, certain NGOs are thus demanding higher taxation on such metals, even a ban on their exploitation.

Moreover their exploitation remains a challenge, since certain coveted sites are far from the coast – such as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) which is a 5-day sail from San Diego (California). Yet despite its share price having dropped tenfold since it was listed on the stock exchange in 2020, TMC has announced that it will be exploiting the nodules in the ZCC in 2025, whether or not the Marine Mining Code has been established. Its CEO Gérard Baron, the former manager of Nautilus Minerals, has estimated that he can raise 85 billion dollars for this project alone following a planned 8.5 billion payment to the island of Nauru, a candidate for exploitation within the CCZ and one of TMC’s partners.

Is it technically feasible?

The technological challenges of underwater mining are enormous, unlike those of the offshore hydrocarbons industry upon which it is based. The nodules, in theory the easiest to harvest, are also the most difficult to access: managing all the cabling required at these depths, conveying the minerals over 4–5 km, surface processing, etc., constitute major challenges. And as with the hydrothermal sulphides and cobalt-rich crusts, the technical issues to be surmounted will be intimately linked to the ecological constraints and the regulations imposed.

Exploitation or precautionary approach?

There have been a number of calls for a moratorium in order to get humanity to delay or abandon underwater mining: by the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, that has rallied over 100 NGOs and institutes to the defence of the deep seas; and in June 2024 by over 800 world experts in marine science from 44 countries, who advocated for the gathering of sound scientific information prior to any exploitation. And even – unusually – by the private sector, through the World Wide Fund for Nature’s (WWF) moratorium: 49 multinationals including Google, BMW, Renault and Samsung have stated that they will not source minerals from the seabed or finance the industry.

At the political level, in 2022 the European Parliament passed a resolution inviting the Commission and its Member States to support an international moratorium, including through the ISA, until effective protection of the marine environment is ensured. In February 2024, it strongly condemned the Norwegian government. Likewise, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (UICN) called on ISA Member States to oppose the industry.

Yet only a small minority (25 out of the ISA’s 168 members) requested a moratorium. France, following a surprise U-turn in 2022, even advocated a total ban on exploitation. Conversely India, China and Russia are pro-mining, whilst the Island States are highly divided over economic development and environmental impact. In short, the future of exploration, and particularly that of underwater mining, is still far from decided!