Doping: a look behind the scenes

After decades of cheating, the fight against doping is making progress. Amid an increase in testing and improvement in screening methods associated with new practices, is the doping era finally losing steam?

Investigation by Alice Bomboy - Published on

From uncontrolled doping to the Athlete Biological

Passport The years when doping was at its peak are not so far behind us! During the 1970s and ‘80s, in the thick of the Cold War, some nations were urging their athletes to cheat. Ten years later, cycling, athletics and football were rocked by one scandal after another. Recently, a State-sponsored doping system was exposed in Russia, which led to a ban on its athletes representing their country at the Tokyo 2021 and Beijing 2022 Olympics. And yet the figures prove that anti-doping efforts are partly paying off. Between 2003 and 2021, the number of samples analyzed in Olympic and non-Olympic sports surged, rising from 151,210 to 241,430. Over the same period, the number of "positive cases", revealing use of a prohibited substance, fell from 2,747 to 1,560, according to the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). In 2019, 1,537 sanctions were confirmed against athletes proven to have violated the anti-doping rules. To identify such violations, it was necessary to develop a revolutionary tool: the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP), adopted as early as 2007 by some sports federations. Rather than detecting the doping substance itself, via a blood or urine sample, this can reveal the effects of doping, which remain detectable in the body longer than the molecule itself, thanks to blood or hormonal biomarkers, such as hematocrit (red blood cell count) and hemoglobin (protein facilitating the transport of oxygen in the blood), etc. Regular monitoring of these biological variables can detect abnormal values, in which case an investigation begins to determine if these are caused by inadvertent contamination of the athlete, a health problem, a change in routine, such as training in the mountains … or an actual case of doping.

25 years ago, the “Tour de Farce”

In the middle of the 1998 Tour de France, a Festina "soigneur" (rider care team member) was arrested near the Franco-Belgian border in possession of hundreds of doping substances including EPO, amphetamines, growth hormones, testosterone and corticosteroids. The team was disqualified from the Tour de France for “breach of ethics”. The reputation of the French rider Richard Virenque, one of the stars in the Festina team, never fully recovered. The scandal made global headlines and reverberated far beyond the world of cycling. In 1999, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) organized a World Conference on Doping in Sport, which led to the creation of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) on November 10, 1999.

Testing athletes, the other Olympic challenge

Nine thousand! That’s the number of samples collected for Paris 2024, by 300 French and foreign testers trained for the occasion. Some 600 "chaperones" also accompany athletes from the time of notification to the end of the sample collection session. While the French Anti-Doping Agency (AFLD) plays a key operational role, the International Testing Agency (ITA) oversees the Olympic anti-doping program. The latter was founded in 2018, following the instances of widespread manipulation of the anti-doping rules during the Sochi Winter Olympics in 2014: the Russian Anti-Doping Agency had switched tainted urine samples with “clean” ones.

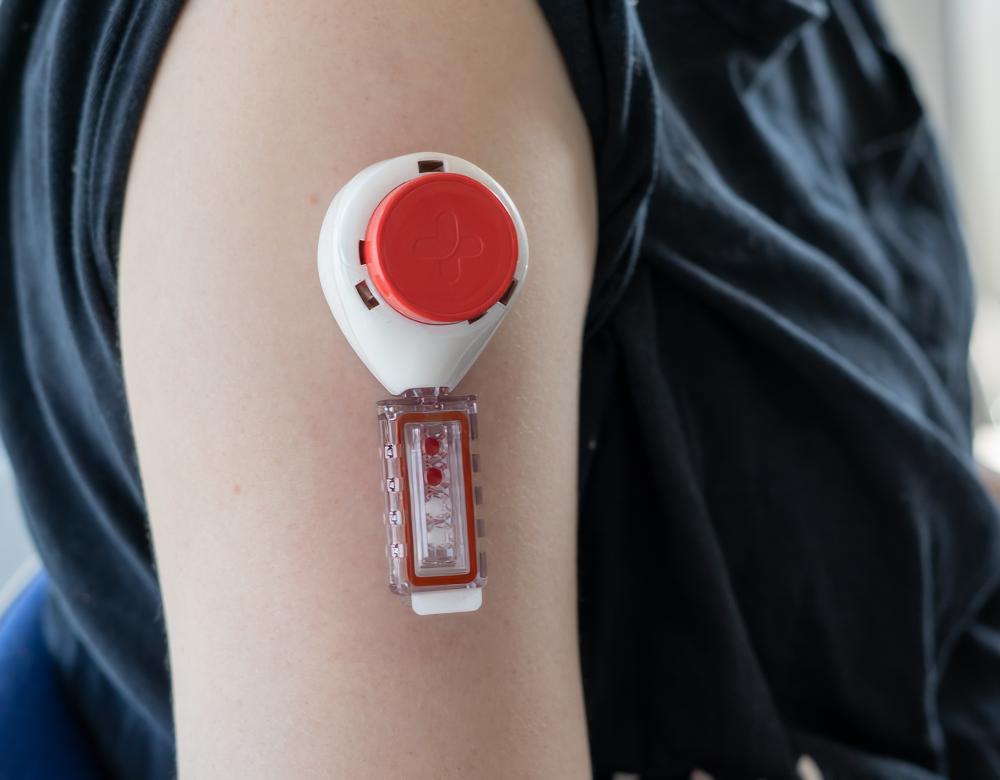

Dried blood for testing athletes (on a massive scale)

A first in France: in 2023, athletes competing in a CrossFit event were tested using the DBS (Dried Blood Spot) technique, in which a device is attached to the upper arm to sample a few microliters of blood. This technique is faster and less invasive than a blood sample and easy to use. More athletes can thus be tested and testing becomes easier in countries where sample storage and transportation are problematic. Not only that, but the blood, once dried, is "fixed", which paves the way to subsequent testing of the samples, stored for ten years, using new techniques. After the London 2012 Olympics, re-analyses led to 73 sanctions and the re-allocation of 46 Olympic medals!

The hazy borderline of doping

At what point does doping begin? For the national agencies and World Anti-Doping Agency, the list of prohibited substances and methods is clear, updated annually and accessible to all. But for athletes, there is sometimes a fine line between non-doping and doping. Accordingly, in 2022, 20% of positive samples tested by the French Anti-Doping Agency (AFLD) were caused by a food supplement: some products are contaminated or contain banned substances, without these being clearly listed in the ingredients. To tackle such doping "due to negligence", in 2018 the AFLD established an education and prevention department tasked with raising awareness among elite athletes and their coaches. Other athletes deliberately exploit doping loopholes. To get away with taking prohibited substances, some might thus dishonestly apply for a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE), which is usually granted to athletes with illnesses or conditions requiring treatment, upon approval by medical experts. Others try to remain below the testing radar thanks to "microdoses" – such tiny doses of banned substances that they are very hard to detect if tests are not conducted straight afterwards. And they tend to take these microdoses at night, since the majority of tests are done between 5am and 11pm. In the event of serious suspicion and a high risk of evidence disappearing, however, a judge may authorize testing at night.

Genetic analyses at the new anti-doping lab

Based on the campus of Université Paris-Saclay, the French anti-doping laboratory is the only body in France to be accredited to analyze anti-doping test samples. For Paris 2024, its workforce has increased threefold: 120 analysts work there, examining blood and urine samples. The lab is now accredited to identify potential cases of gene doping too. This involves the manipulation of an athlete’s genes or cells so that their body increases production of a substance on the Prohibited List, such as the growth hormone, steroid hormones or erythropoietin. To date, despite suspicions, no case of gene doping has been detected.

Is doping more of an issue with men than women?

At the Beijing Olympics, in 2022, the Russian figure skater Kamila Valieva was the firm favorite to win. But the positive result of a test conducted a few weeks earlier turned the sporting dream into a nightmare for the 15-year-old athlete, who ended up falling while competing. Slender, young … and a woman, she simply didn’t fit the general public’s perception of a “cheating athlete”. Indeed, various international studies report that doping is less common among women than men. And yet, in France, the AFLD believes that doping cases are proportionately comparable among the sexes.

Technological doping?

At the Rio Olympics, all three of the medallists in the men’s marathon were wearing trainers that no one had seen before: Vaporfly (Nike). Their secret? A carbon-fiber plate, which improves the shoe’s elastic qualities, as well as a 40mm stack height, which cushions impact. In light of the number of victories racked up by athletes wearing this ground-breaking shoe, World Athletics has since issued new rules to prohibit the use of prototypes. Vaporflys are authorised, but not the most recent, ultra-sophisticated models, with more than one embedded carbon-fiber plate or a thicker sole.

From amateurs to great champions: is doping a universal problem?

The doping figures are altogether surprising: there are positive cases not only in the Olympic sports, but also in non-Olympic disciplines, and they concern elite athletes and amateurs alike. As for the reasons driving athletes to take banned substances, by their own admission these are manifold: to earn money, or the admiration of their entourage, to recover after an injury, to save up for the end of their career to avoid falling back into the financial insecurity they knew growing up, to give into pressure from their teammates or their government… In a nutshell, it’s hard to pin down a typical profile of an athlete who is more at-risk than others! As such, testing now targets all athletes, rather than solely those performing at national and international level, as was the case before: in 2023, 20% of the 12,000 samples taken by the French Anti-Doping Agency (AFLD) concerned regional or county-level athletes. In amateur circles, with coaches providing less supervision and little or no education in doping, the trends regarding doping due to negligence or out of ignorance are high, in the same way as doping on an athlete’s own initiative, without any medical supervision. On a final note, on-trend sports pursuits among 16–25-year-olds are also a cause for concern at the AFLD. Bodybuilding, for example, has become a hugely popular sport among this age group, practiced by 43% of them. And yet it has a long, checkered history with doping. In 2024, the AFLD is unveiling the e-learning platform Podium to raise teenagers’ and young fitness enthusiasts’ awareness of substance use in gyms.

But why such efforts to combat doping?

By harmonizing the rules in favor of "clean" athletes, the fight against doping helps to create a fair playing field for all. Athletes who take prohibited substances gain an undeniable competitive edge against their opponents who don’t resort to cheating to achieve personal or team bests on a physical, mental and human level. With doping, excelling personally or collectively in this way is no longer only reliant on the athletes’ efforts, but on the means expended to get hold of a given substance! There are vocal advocates of doping who unashamedly embrace such an attitude, however, with events like the Enhanced Games due to take place for the first time at the end of 2024. This has set alarm bells ringing among anti-doping experts, who cite another reason for their concern: when athletes use performance-enhancing drugs, they are putting their health at risk. Cardiac, hormonal or fertility problems, tumors … the list of potential long-term effects for athletes taking banned substances is long. Although it is likely not the only cause, doping is suspected to have been a factor in the early deaths of the cyclist Tom Simpson in 1967, the sprinter Florence Griffith-Joyner in 1998 and the footballer Gianluca Signorini in 2002. Sport and its champions play an important role in the education of young people, who feel inspired to be like their role models, whether on the field or in other areas of life. When they, or amateur athletes, resort to doping, they often use substances obtained on the black market, online, with no medical surveillance. This can take an even greater toll on their health than the risks taken by their idols.