Endangered languages: how can they be saved?

Thousands of indigenous languages – belonging to the heritage of humanity – are in danger of extinction. Digital technology, an unexpected ally, has been called to the rescue.

by Barbara Vignaux - Published on

The death of languages is not a new phenomenon, but it is accelerating. More than half of the languages currently spoken in the world are expected to disappear by the end of the century. This alarming forecast led UNESCO to declare 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages. How can this world heritage be preserved? Digital tools are precious to linguists in the field: they facilitate audio and video recordings, simplify archiving, enable online access to material collected, and more. Can they contribute to saving endangered languages, and, if so, in what way? To what extent do current collaborations between linguists and computer scientists hold promise? An update on current research.

An accelerating disappearance

By the end of the 21st century, half the languages spoken in the world may disappear.

The disappearance of languages is not new. In the 20th century alone, Shuadit (or Judæo-Occitan) in France, Ainu in Japan, Sened (a Berber language) in Tunisia; and since the beginning of the 21st century, Eyak in Alaska, Yawalapití in Brazil, Areba in Australia, Mandan (a Siouan language) in the United States, have, along with many others, joined the cemetery of dead languages. What is more recent is the acceleration of the phenomenon. Michael Krauss, an American specialist in Alaska, sounded the alarm in 1991. His work is at the origin of the commonly accepted estimate that 50%. Of the languages are threatened with extinction by the end of the century. The first edition of UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger was published five years later, in 1996, followed by an indicator of vitality of the world’s languages in 2003. The disappearance of the world’s linguistic heritage is due in large part to population displacements provoked by the rural exodus, the construction of dams, the exploitation of natural resources, and even the disappearance of certain habitats, such as Pacific islands that have been gradually submerged by the rising waters. In China, Brazil or India, languages have been lost in merely two generations when grandchildren, opting to use official languages such as Mandarin, Portuguese or Hindi, lose the ability to converse with their grandparents. According to Nicolas Quint, a linguist at the CNRS, ‘nearly all languages are threatened, except the official ones that are the main languages of instruction at school.’

Impending impoverishment

The world is rich in thousands of languages, but most of these are oral and die with the passing of the last speaker. As a result, the transmission of myths, proverbs, songs and various types knowledge (traditional medicine and pharmacopoeia, for instance) is disrupted as is the transmission of a specific worldview. According to French linguist Colette Grinevald, one of the first in France to fight for the preservation of endangered languages, ‘The attempt to identify what languages have in common – languages as different as Franco-Provençal, Quechua, Amazigh and Wolof – is a search for the universality of language.’

Africa less affected

Two regions of the world are particularly affected by language impoverishment: Australia and North America, where 90% of existing languages may disappear by the end of the century, replaced by English which has become by far the majority language. In Africa, bi- and multilingualism remain common. People tend to have a mother tongue, plus a lingua franca (such as Hausa), and also speak a colonial language, such as Portuguese, and in many cases another African language too. That being said, monolingualism is becoming increasingly common, observes Nicolas Quint, a CNRS linguist. In Gabon and Cameroon, for example, many young people speak only French.

Precious digital tools

For about twenty years, digital tools have contributed to the development of field linguistics at the service of endangered languages.

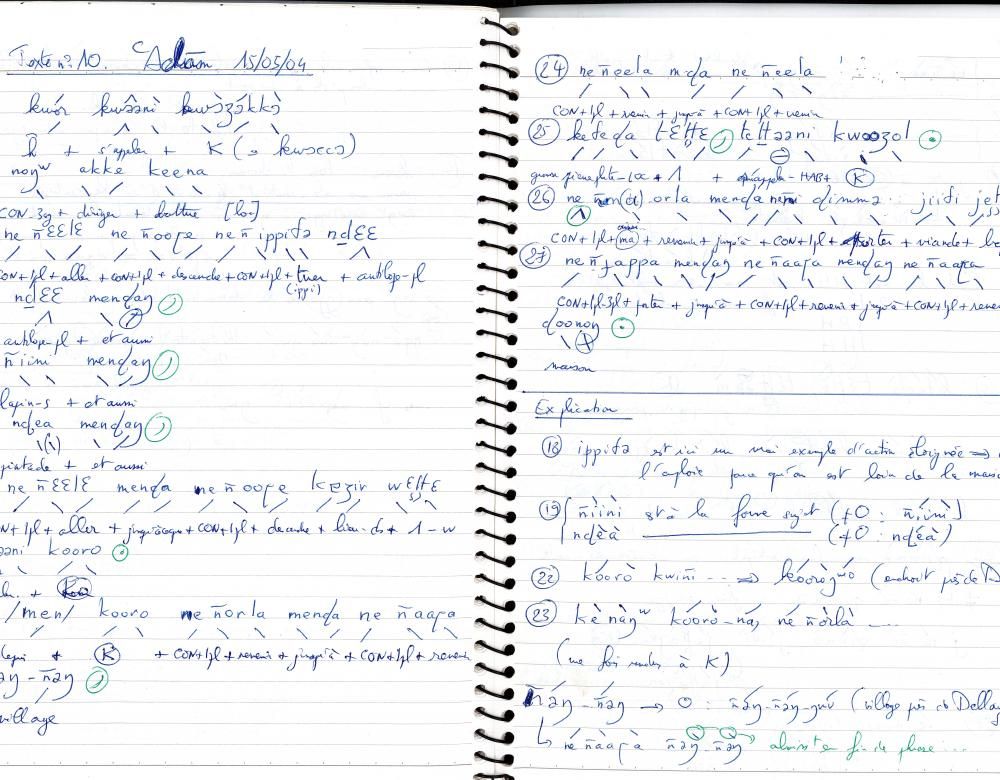

The goal of field linguistics is to collect primary speech data from communities of speakers directly in their context of emission: preparation of meals, marriage, stories, prayers, rituals, etc. The discipline is not new, but it has benefited extensively from digital tools: audio and video recorders, especially useful for data collection in the case of oral languages; database storage, essential for the transport and durability of archives, and so on. In the so-called ‘documentation’ phase, digital cameras, laptops and computer files have gradually replaced notebooks, pens, cameras and tape recorders. Nevertheless, a good part of the work of the linguist remains artisanal. It takes 40 hours on average to phonetically transcribe an hour of oral speech without segmentation, meaning without any separation between words. This is the necessary preliminary step before the analysis of a language. This second stage, known as ’description’, involves identifying terms, devising a suitable alphabet, translating, and developing a dictionary and grammatical rules. Digital technology provides useful tools. And the languages that have the best chance of surviving are those that already enjoy a virtual existence on websites, Wikipedia pages or online news sites.

The spectre of zombie linguistics

Accumulating considerable volumes of words from endangered languages is falling into the pitfall of what Bernard C. Perley, an American anthropologist, described in 2012 as zombie linguistics and criticized for the way in which the approach generates ‘artefacts of technological interventions.’ Pereley’s tone is fierce, but his questioning is shared by other linguists: when and how will the accumulated data be analyzed? Wouldn’t it be better to focus first on safeguarding existing archives, preserved in notebooks, tapes and films, and sometimes abandoned on the shelves of researchers?

Open-access online portals

Documented languages are being preserved by being put online. Several Internet sites have made this their specialty.

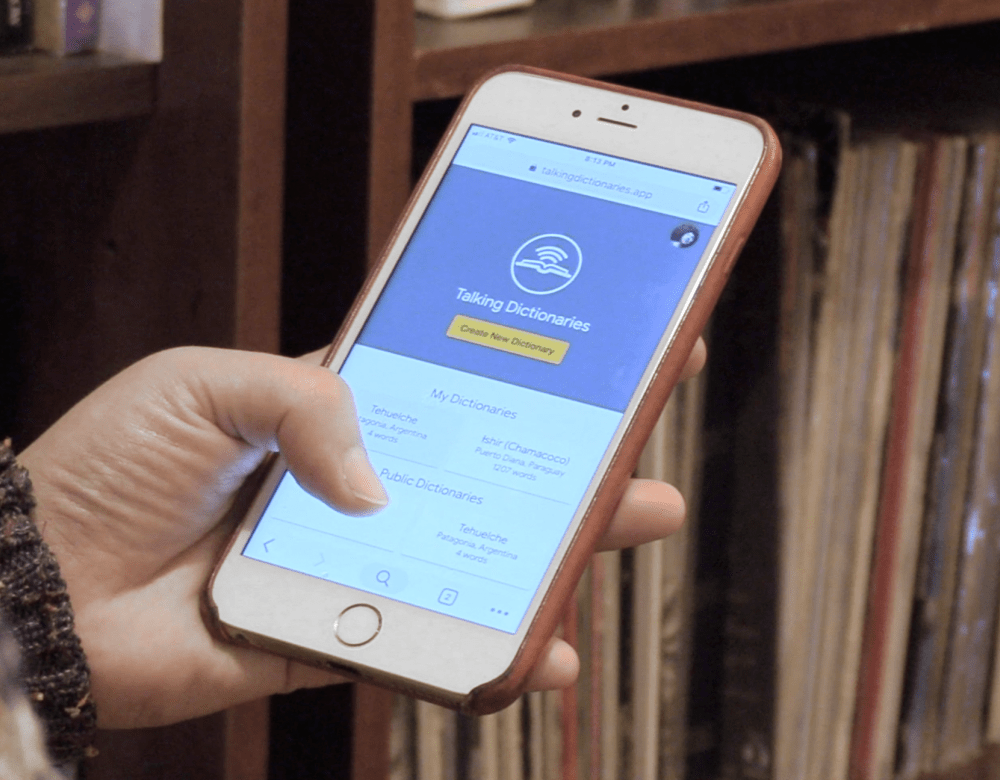

In the 2000s, websites were created to archive material collected by field linguists. The most famous is the Endangered Languages Documentation Program (ELDP). Benefitting from the support of the University of London, the ELDP awards research grants to PhD students and researchers to conduct fieldwork and put their data online: audio recordings, photos, videos, transcriptions and translations. Since its creation in 2002, the ELDP has funded more than 400 projects. This vast linguistic library hosts the ultimate testimonies of certain languages that are in danger, extinct or on the brink of extinction. The Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages in Oregon, United States, trains local speakers in collecting, cataloguing, publishing and disseminating words and phrases in their native language. The Institute’s website features over a hundred ‘talking dictionaries,’ each containing tens of thousands of terms. Other initiatives are more local in nature, such as the ELA (Endangered Language Alliance), which focuses on the more than 800 languages spoken by communities in New York City. There are not nearly as many Francophone sites. One of the exceptions is Sorosoro, which lists endangered languages in Europe. Translated into French, English and Spanish, it strives to establish a bridge between the academic world and the general public.

Revived languages

‘A language is a dialect with an army and navy.’ This adage, attributed to linguist Max Weinreich (1894–1969), a specialist in Yiddish, points to the extent to which the state defines what constitutes a language as opposed to a dialect. State support has brought ‘dead’ languages back to life in the 20th century, including Hawaiian, Hebrew and Maori. One of the official languages of New Zealand since 1987, Maori will be included on the school curriculum starting in 2025, with as much time devoted to its teaching as science subjects. Less than 4% of the population speaks the language, but the government hopes that 20% will have a basic knowledge by 2040. On the photo, New Zealand pupils perform traditional Maori dance.

Using AI for endangered languages?

Can artificial intelligence facilitate the work of linguists?

The first attempts have not been conclusive, but research continues. The dream of any technophile linguist is to have speech recognition software capable of phonetically transcribing an oral recording of an unwritten language – a prerequisite for linguistic analysis. An attempt was made to develop such a tool using three little known languages of the Bantu family (400 speakers in some twenty countries): Basaa, Myene and Embosi. The French-German collaboration, entitled BULB, for Breaking the Unwritten Language Barrier, had linguists and computer scientists working together on a project between 2015 and 2018. But the hundred hours collected for these three languages did not suffice to generate an algorithm capable of automatically transcribing something said in Bantu. The problem is that artificial intelligence (AI) programmes ‘feed’ on huge databases (10,000 hours of speech for the Google Home device, for example). Which is why transcription software works well for ‘big’ languages spoken by many individuals. This is why, when it comes to transcription, it is not easy to reduce the work of linguists. The algorithm that the BULB team tried to generate to automatically translate Bantu into French enabled the programme to identify only a few Bantu terms. Due to a lack of data, it is also highly unlikely that a machine translation (of the Google Translate type) will ever exist for minority languages. Nevertheless, research continues on the use of AI for preserving endangered languages – for example, for transcribing so-called ‘tonal’ languages, which have remained a challenge for linguists.

Respeaking for Lig-Aikuma

Conditions in the field do not always lend themselves to high-quality recordings, in which the speech stands out distinctly from ambient sounds. The aim of the Lig-Aikuma app for smartphones, developed by Laurent Besacier at the Grenoble computer science lab (Lig), is precisely to generate clean data using the principle of respeaking: a speaker of the language in question slowly repeats, bit by bit, what was recorded in the field. The app can also be used to geolocate the recordings, check quality in real time and link them to metadata (place, date, speaker’s age and origin).

Revitalization using apps

Keyboards adapted to different language writing systems, audio recording and playback, offline mode (for zones without internet coverage), enhanced search tools, semantic classifications, grammatical explanations: these are just some of the features available on the ‘talking dictionaries’ developed by the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages, Oregon. Objective: to facilitate and encourage the daily use of a language – its revitalization – among young people. ‘A phone app changes the outlook on a language!’ comments linguist Mark Van de Velde.

Europe is also concerned

Europe is a continent of linguistic homogeneity, with only one language per 2.5 million inhabitants as compared to one for every 500,000 inhabitants in Africa and one for one million in America. That being said, half of the languages spoken in Europe are endangered, including Celtic languages, Yezidi, Yiddish, Karelian and Basque. Twenty-five European countries have signed and ratified the Charter for Regional or Minority Languages adopted in 1992 by the Council of Europe (which has 47 members). Eight have signed but not ratified, including France, because doing so would necessitate revising its constitution, for which there is no consensus so far. Fourteen other states have not yet signed the charter.

Koalib: digitized archives

Nicolas Quint, a CNRS linguist, dates to 2010 his switch to digital technology. He has since digitized his paper archives. Here is a transcript of Koalib, a language with an unusual history. While it has experienced a decline since the Sudanese civil war of the 1980s in the government-controlled zone, where Arabic is the language of instruction, it used daily in rebel areas (where Arabic is no longer taught in school), including by children. In addition, 10% of its 150,000 speakers read in Koalib (written using a modified Latin script): Bible, reading primers, collections of tales.