A new attitude towards endometriosis

For a long time, endometriosis was an overlooked disease, but it is now enjoying a form of social recognition and there is ever more research into the condition.

Investigation by Kassiopée Toscas - Published on

The facts are alarming. Endometriosis, a persistent inflammatory gynaecological disorder, affects nearly one woman of childbearing age in ten. It causes chronic pain and sometimes infertility, but continues to be diagnosed seven to ten years late. Formerly ignored, today, it has finally been recognised as a major issue by both politicians and scientists. France launched a national endometriosis strategy last January and became one of the first countries in the world to treat the condition as a genuine public health issue. Gynaecologists, reproductive specialists, geneticists and epidemiologists are attempting to learn more about its distribution, causes and physiological processes, and improve its diagnosis and management. But their research is still in its infancy.

Many grey areas

Long ignored and biologically complex, endometriosis and its mechanisms are still poorly understood today.

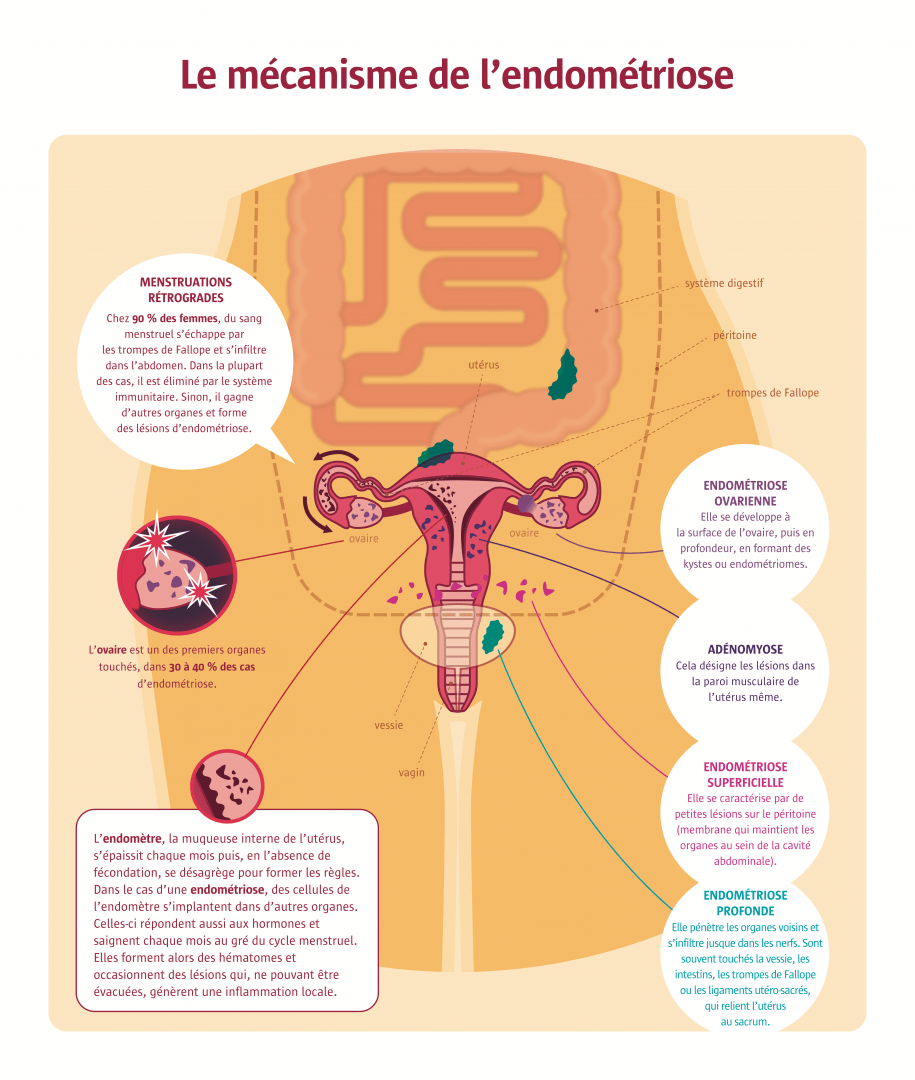

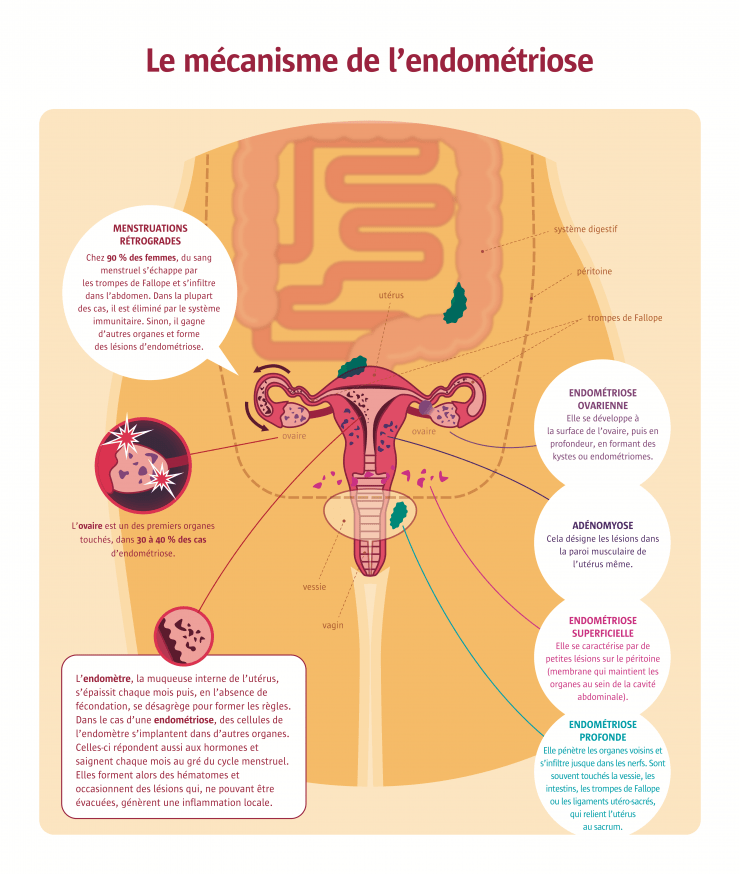

Endometriosis probably already affected the first females of Homo sapiens. Clinically described by the Austrian doctor Carl von Rokitansky in 1860, it is caused by the presence outside the womb of endometrium – a mucous membrane usually confined to the uterus. However, it was not until the 21st century that we began to grasp the extent of its impact on women’s health, and only in September 2020 was it added to the curriculum of the second cycle of medical studies. At last, a national endometriosis strategy was announced in January 2022. So why has the disorder taken so long to be recognised? Menstrual pain – the main symptom of endometriosis – was long seen as a natural phenomenon in women, a human discomfort with no pathological cause. But preconceptions about female pain have gradually changed, knowledge has improved and researchers today know that endometriosis is a genuine disease with complex physiological mechanisms. How does endometrium appear outside the uterus? Why is it not destroyed by the immune system? No hypothesis has yet managed to explain all observed cases, which are very diverse. The retrograde menstruation theory suggests that endometriosis occurs due to the retrograde flow of sloughed endometrial cells and debris via the fallopian tubes into the pelvic cavity during menstruation. However, that flow occurs in 90% of women, but only 10% of them suffer from the condition, so there must be other causes. An increasing volume of research is attempting to unpick the tangled factors in play. Image | A disease known since ancient times Already in the 5th century BCE, Greeks described symptoms of gynaecological conditions that were strangely similar to those of endometriosis: a menstrual disorder leading to uterine pain and even infertility, with pregnancy as the remedy. The condition may even have been alluded to by ancient Egyptians as far back as 1855 BCE. Throughout history, scholars have discussed similar symptoms, seen as signs of a ‘wandering’ uterus deprived of its reproductive capability in ancient times, or the consequences of sin and demonic possession in the Middle Ages. But all commentators shared one opinion: uterine pain was due to deviant behaviour.

A disease known since ancient times

Already in the 5th century BCE, Greeks described symptoms of gynaecological conditions that were strangely similar to those of endometriosis: a menstrual disorder leading to uterine pain and even infertility, with pregnancy as the remedy. The condition may even have been alluded to by ancient Egyptians as far back as 1855 BCE. Throughout history, scholars have discussed similar symptoms, seen as signs of a ‘wandering’ uterus deprived of its reproductive capability in ancient times, or the consequences of sin and demonic possession in the Middle Ages. But all commentators shared one opinion: uterine pain was due to deviant behaviour and not a genuine disease.

Exceptional cases

In rare cases, endometriosis lesions can be observed on organs and can even be found in some completely unexpected patients.

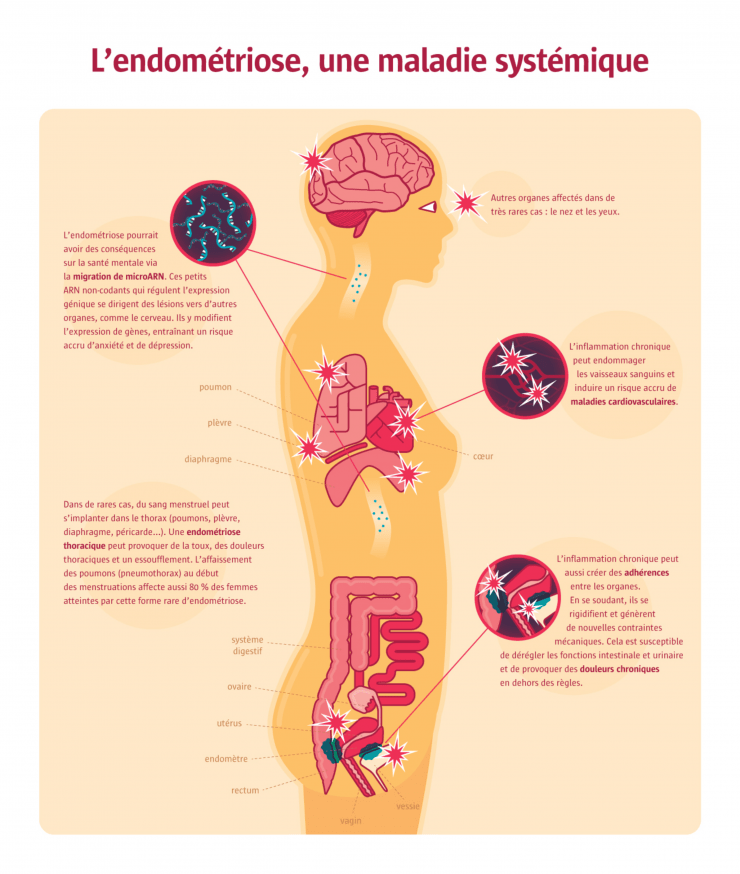

Unusual cases of endometriosis have led to new, sometimes controversial hypotheses. Indeed, organs distant from the uterus can show lesions – lungs, pleura, diaphragm, pericardium, brain, nose and eyes – leading to a string of new symptoms. The phenomenon may be explained by endometrial cells escaping like tumour cells into the vascular or lymphatic systems. Very rare cases have even been observed in female foetuses. Those cases could be caused by the dispersal of endometrial tissue outside the uterus during the formation of organs. Lastly, premenstrual girls have also developed endometriosis … and so have men, after high-dosage oestrogen therapy to treat prostate cancer or an autoimmune or viral deficiency, for instance. This may result from already differentiated cells turning into endometrium cells under hormonal stimulation. The cells involved may be the remains of a Müllerian duct (the embryonic organ that develops into the reproductive tract in females, but atrophies in males) after defective organogenesis, or cells from the cavities holding the lungs, heart or viscera, since they all derive from the general cavity of the embryo, itself linked to the Müllerian duct. Another, more recent theory suggests the disorder is caused by the reprogramming of extra-uterine stem cells. Indeed, a team from the Yale School of Medicine has shown that bone-marrow stem cells can become endometrial cells.

A complex disease

The symptoms of endometriosis are extremely varied and a better typology of the disease is needed.

Scientists are unanimous: there are different forms of endometriosis. However, there is no correlation between the different profiles identified – ovarian, superficial and deep infiltrating endometriosis, and adenomyosis – and the aggressiveness of the disease or its symptoms. Infertility only affects 30 to 40% of women suffering from endometriosis, whether it is caused by chronic inflammation (which can reduce the possibility of implantation or even fecundation) or the presence of ovarian cysts (which impact the stock of oocytes). A 10% risk of premature miscarriage was also reported by French researchers in 2016. As for pain, not all the women suffer from it. And even in those who do, the symptoms vary tremendously, ranging from dysmenorrhoea (pain during a period) to dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse), together with noncyclic pelvic pain and painful urination or defecation. So the next great challenge will be to characterise the disease’s symptoms and identify subgroups for each profile according to parameters that are still to be defined – possibly indices of lesion proliferation or hormone receptor rates – in order to predict the progression of the disorder and prescribe appropriate treatments. The new classification could also be based on the level of pain caused by certain stimuli, or microRNAs, perhaps with a variable profile according to the type of endometriosis. All possibilities are being explored.

Is the immune system implicated?

While half of all cases of endometriosis are linked to hereditary transmission, the rest are caused by a complex combination of factors.

It is hard to define the source of endometriosis with certainty. Either the endometrium is pathological and more aggressive, or the immune system is passive and allows the endometrium to implant itself anywhere. Those hypotheses are not exclusive. In 2021, a team from the Institut Cochin in Paris concluded that 51% of cases were genetic in origin, but a very large number of genes are implicated in this ‘heritability’ and geneticists have only been able to identify a few. The rest are referred to as ‘missing heritability’ (also known as ‘genetic dark matter’). As with every polygenic disease (one that involves a number of genes), a synergy of several genetic variants undoubtedly triggers the disease through, for instance, a dysfunction of the immune system. Indeed, immunity plays a key role in endometriosis because it can stimulate the growth of lesions when overactive and cause chronic inflammation. In 2020, another team from the Institut Cochin observed that certain innate immune cells (macrophages) played a critical part in the progression of endometriosis, which is in fact associated with an entire series of autoimmune pathologies including lupus, Crohn’s disease and scleroderma. So immune dysfunction could be the prime factor in endometriosis, but that remains to be demonstrated.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors may play a role in the progression of endometriosis, particularly diet, whose still uncertain role is being investigated by researchers. Like certain organochlorine pesticides, the dioxins present in animal fat are among the endocrine disruptors (able to interfere with our hormonal system) that are linked to endometriosis. Exposure to synthetic hormones that imitate oestrogens could also facilitate the disorder, as shown by the diethylstilbestrol scandal. Prescribed for pregnant women until the 1990s to prevent miscarriages, the drug increased the incidence of endometriosis in girls who were exposed to it in utero.

Increasing awareness among professionals and the general public

Endometriosis is poorly known. So it is poorly diagnosed, poorly reported and poorly understood. A vicious circle observed worldwide…

Even today, it takes an estimated seven or even ten years before endometriosis is diagnosed, according to the preliminary conclusions of research based on the French cohort of CompareEndo, made up of nearly 5,000 patients. Stakeholders all over the world – doctors, associations, expert patients – believe that to deal with these medical shortcomings and repeated misdiagnoses, priority should be given to the promotion of awareness among the general public and, even more importantly, the training of present and future healthcare staff – practising doctors, paramedics and medical students. Deficient screening leads to deficient epidemiological data. Today, we think the prevalence of endometriosis is around 10% for women of childbearing age. However, that remains a rough estimate – a high bracket for some epidemiologists; a low one for others. Many other questions remain unanswered, such as the precise proportion of serious cases and female infertility, and the geographical distribution of cases. All are obstacles to a proper understanding and characterisation of the disorder. All countries face the same problems. Critics point to a lack of training for healthcare staff and the absence of national registers recording the number of cases diagnosed. So we can see the full extent of the challenge.

France’s national strategy

Last January, the French government announced a national strategy to combat endometriosis, France being the second country worldwide (after Australia) to treat the disorder as a public health issue. The planned budget – 20 million euros – has been welcomed by patient groups, who see it as the beginning of recognition. Until now, research has mainly been funded by patient donations and has suffered from a virtually total lack of public funding. Aside from basic clinical research programmes, the budget will be used to set up a database supplied with information from the six existing national cohorts, since a national register would be too expensive.

Developing diagnosis tools

Early screening requires the identification of a biological signature. That is still a distant prospect, even though diagnostic methods are evolving.

Led by many biotech start-ups, the search for biological endometriosis markers is gathering momentum. MicroRNAs, for instance, seem to be a promising possibility. The little non-coding RNAs regulate gene expression (epigenetics) and their levels can be unusually high or low in endometriosis patients. In February 2022, there was excitement about a saliva test to detect those markers: the Endotest developed by Lyon start-up Ziwig. The research is seen as relevant, but is still at a very preliminary stage, since microRNA production depends on the individual’s physiology and no other laboratory has so far been able to reproduce the results observed. As for genetic markers, they are reliable. According to geneticists specialising in the disease, a diagnosis tool could take the form of a DNA chip, a genetic tool that might cover all types of predisposition to endometriosis – as long as they are successfully identified, which may involve a long, complicated, costly process. The future of diagnosis could rather lie in a combination of genetic, epigenetic and even proteinic markers: a complex disorder means a complex biological signature. While they wait for those state-of-the-art tools, researchers are turning to diagnostic algorithms based on artificial intelligence to avoid resorting to systematic surgery to detect lesions. Generally, good medical imaging and a questionnaire are enough. So the days of routine surgery are over, already a genuine diagnostic revolution in itself!

Developing new treatments

Many leads are being explored to develop new treatments, but it will be a long process.

The management of endometriosis sufferers has changed a lot over the past few years. Instead of systematically operating, doctors now treat each case individually and protect fertility at all costs with in vitro fertilisation and oocyte cryopreservation. As for the treatments, for the time being, they only have the suspensive effect of blocking the menstrual cycle. Drugs include oestrogen and progestin pills, prescribed as first-line therapy. The complete ablation of lesions is still the only way of eliminating the disease and even that does not prevent recurrence. That said, many innovative non-hormonal treatments are being studied (although work is still at a very early stage). They notably include epigenetic therapies (modifying gene expression). In 2018 and 2019, a team from the Yale School of Medicine identified two promising microRNAs to correct the expression of certain genes that are predisposing factors in endometriosis, and they observed a better prognosis in animal models. Combinations of microRNAs are also being studied. Another possibility that works on mice acts on innate immunity, particularly the profile of macrophages (a type of white blood cell), in order to reduce lesions. One things seems certain: there will be no magic pill to treat endometriosis. Progress will be gradual, because our biology shows a complexity shaped by 3.5 billion years of evolution.

Inhibiting a key gene

In 2021, a team from Oxford University studied one of many genetic variants linked to the risk of severe endometriosis. They identified the variant by comparing genetic data from women and families who did or did not present multiple cases of endometriosis. It turned out to be the gene that codes for the NPSR1 membrane protein. They tested its inhibiting effect on mice that had been injected with fragments of endometrium to simulate endometriosis. Their conclusion was that the inhibition of NPSR1 reduces inflammation and pain. However, when dealing with a complex, polygenic disease, a treatment that acts on a single gene will probably only be useful in treating a small fraction of serious cases.