Education in the age of artificial intelligence

AI is breaking into educational environments, opening new perspectives for teaching and learning and arousing concerns about the relevance of its educational uses.

Investigation by Kassiopée Toscas - Published on

Education shaken up by AI

AI is being used in schools, both in France and worldwide. Smart learning applications for French (Lalilo and Navi) and mathematics (Adaptiv’maths, Mathia, and Smart Enseigno) have been used in Years 2, 3, and 4 for three years now. In 2024, AI is expected to make its début in secondary schools with Mia Seconde, a revision application available on tablets and smartphones, intended – according to ministerial terms – to ‘raise standards’.

Against the backdrop of the race for innovation and increasing use of digital technology in education – accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic – AI is presented as a solution to social inequalities in learning and the declining performance reported year after year by PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) surveys. According to its advocates, its main advantages are personalised exercises and monitoring. However, this promise will not necessarily be kept, warn educational science researchers.

The launch of ChatGPT, a generative AI, has sparked strong reactions from teachers, who fear that it will hinder students from developing thinking skills. According to a May 2023 study in France among Yubo users aged 13 to 25, one in five students use ChatGPT for their school or university homework.

Generative AI thus poses several new challenges for educational systems. These challenges are practical, educational, and ethical: confidentiality of student data as well as treatment of biases and stereotypes carried by algorithms.

UNESCO sounds the alarm

In September 2023, UNESCO published the first global guidance on GenAI in education, recommending the implementation of data protection standards and the use of generative AI in the classroom from age 13 only; less than 10% of schools and universities currently monitor its use. The UN also warns against the haste with which applications are rolled out, primarily for economic reasons and in the absence of control or regulation. The AI in education market is booming, with a global turnover estimated at EUR 4.3 billion in 2024, quadrupling by 2032.

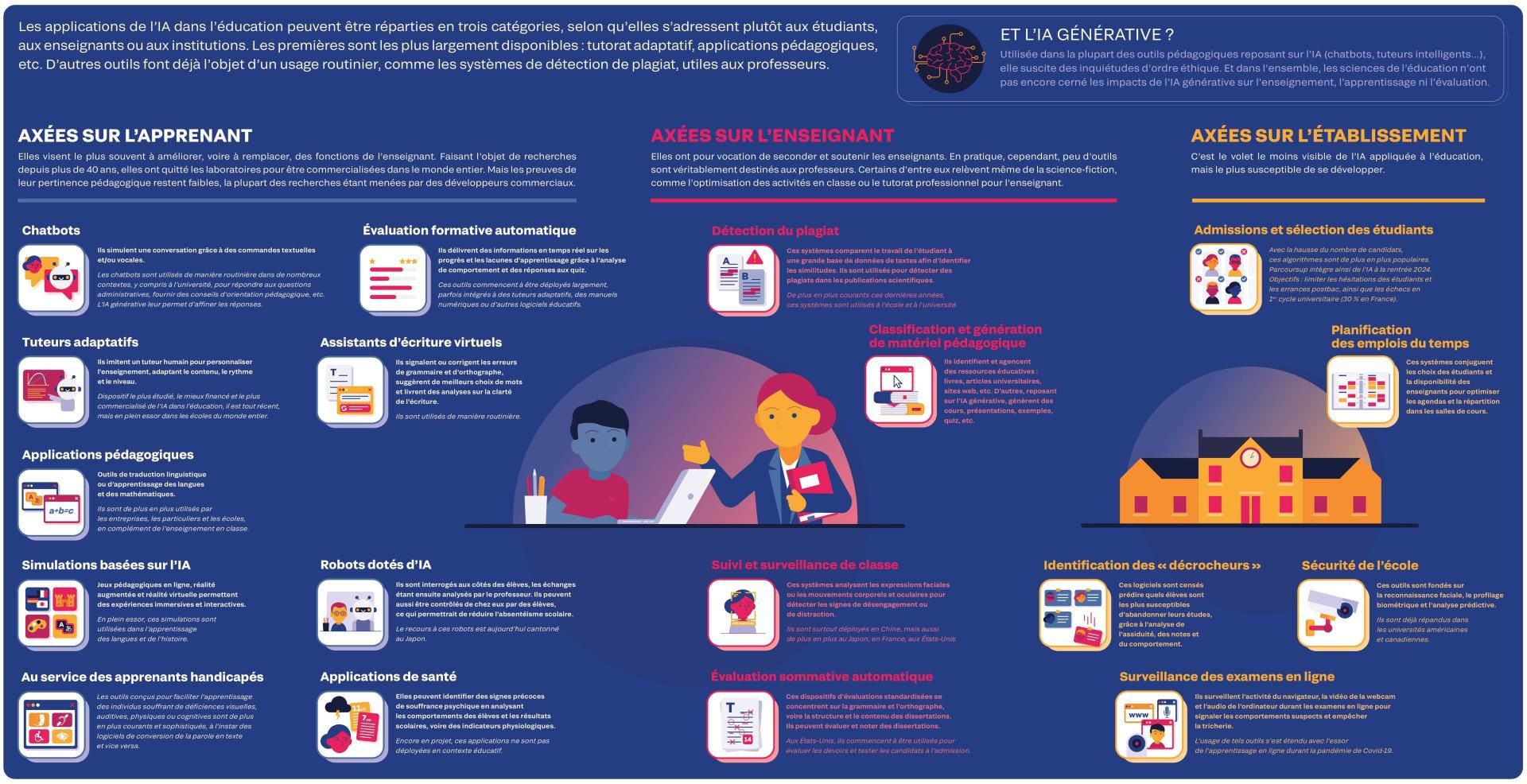

AI applications in education

A way to reduce educational inequalities?

One of the advantages of AI in education is the development of inclusive educational materials which integrate technologies to assist students with disabilities, such as speech transcription to help the hearing impaired or audio reading for the visually impaired.

In developing countries, AI is also being used to close the literacy gap between low- and high-income students. For example, in Brazil, the Letrus programme is used by some 200,000 pupils and students to learn how to write. In sub-Saharan Africa, where EdTech (educational technologies) is already very present, the use of AI compensates for the lack of teacher training, like the Teacher.AI chatbot in Sierra Leone.

While they can reduce inequalities in access to education, these solutions could exacerbate others, such as the new ‘digital divide’: no longer concerning the material availability of technologies, which is now commonplace, but education in digital technology at home, which is very unequal depending on social backgrounds. However, like overexposure to screens, harmful use of AI – such as a lack of critical distance from algorithms – also penalises the most disadvantaged.

Finally, the educational tools currently marketed are based on algorithms that were not designed for educational purposes: large-scale language models, most often American, trained from data reflecting Western cultural norms and containing social, racial, and gender biases. As such, they risk aggravating existing prejudices through the content taught or ‘dropout’ identification systems.

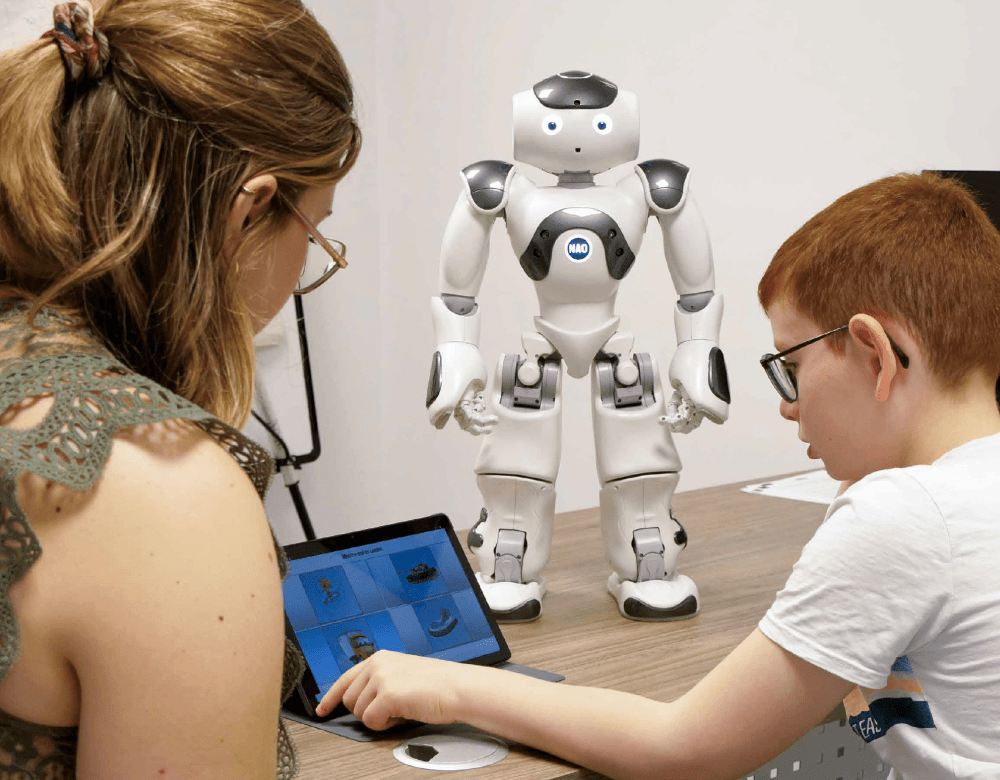

Robots supporting autistic students

AI-assisted robots to improve the attention span of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), their understanding of instructions, and their social skills: this was the subject of a three-year social robotics experiment conducted in Nancy by the Jean-Baptiste Thiéry association in conjunction with Lorraine University. Apart from cases of severe intellectual disability, these children interact more easily with a robot, the behaviour of which is more predictable than that of a human being. Even better, the skills acquired are transferred into social interactions, particularly in the area of communication.

Personalisation at the heart of debates

AI’s core promise is personalisation of learning. As such, a host of adaptive tutoring platforms offer courses with personalised schedules, courses, exercises, and assessments. This ‘techno-solutionist’ mirage is denounced by sociologists, while schools desperately need more human resources.

Educational sciences point out that this is an old promise with limited scope: the adaptive approach is currently solely based on performance criteria. It therefore risks creating a vicious circle and worsening cultural inequalities: a student who lacks self-confidence will process tasks more slowly and will be offered simpler tasks by the algorithm.

Furthermore, the tools currently available do not really personalise exercises: they simply classify students with reference to typical paths, thereby tending to standardise learning... rather than individualising it! By reducing education to a series of tests and measurable results, as if learning consisted of accumulating information, these tools also risk privileging the most quantifiable subjects and neglecting the collective and social aspect of teaching and the individual needs of learners. Public research is therefore striving to design ethical AIs that support learners at their request, within the framework of an explicit dialogue, instead of automatically guiding them and delineating their path by prejudging their choices and level.

An ethical learning companion

At Lorraine University, a pioneering project, launched three years ago, aims to develop a learning companion that complies with the principles of ethical AI: respectful of personal information, non-discriminatory, transparent, and explicitly placed under human control. The algorithm's training data is carefully selected upstream: a radical change, because language models, like ChatGPT, are trained on considerable content data, without distinction of origin or quality. Another new feature is that this companion, called 3PEN, is trained in interaction with the user, by progressively confronting their reactions.

Support for teachers?

AI is often presented as a useful aid to teachers, because most applications are supposed to accomplish some of their work, such as organising activities, designing lessons, and marking homework. AI can also be used to automate tedious, administrative, or educational tasks, such as marking. This promise of time saving, brandished since the existence of the first digital tools, is rarely kept: due to a lack of training, use of these tools has, to date, rather led to... an increase in working time.

That being said, several tools can prove valuable, such as anti-plagiarism software, which will be improved with successive versions of ChatGPT. Generative models can also help write lessons, slideshows, and quizzes. A US study revealed that 50% of teachers already used ChatGPT in their work, including 10% on a daily basis!

In any case, the tool must truly support the teacher, not replace them. Certainly, AI can contribute to designing lessons, but it is the teacher who sets the educational goals and controls the content, because the data feeding most algorithms is neither reliable nor recent. It is also the teacher who explains reasoning that algorithms do not always provide, their internal mechanisms remaining a ‘black box’ even for their designers. While waiting for transparent models, generative AI is a great opportunity to sharpen the critical thinking of young people, for example, by asking them to identify the limits and biases of ChatGPT. At university, some teachers are already using ChatGPT for this purpose.

A mundane story of innovation?

Some technical revolutions have shaken up teaching methods, such as printing, which fostered reading and writing, and the ballpoint pen and the calculator, which rendered calligraphy and mental arithmetic obsolete. Others failed to be included in teaching practices, like school television in the 1970s or the first microcomputers, as these tools dispossessed teachers of their role as game leader. This brief look back suggests that an innovation is more likely to be adopted if it respects the teacher’s authority and their monopoly on knowledge transfer.

What school for the future?

If history is anything to go by, it is likely that AI will be incorporated into the education system without calling into question its founding principle: the teacher-student relationship. That said, the gradual privatisation of education could change the situation, with some researchers fearing that the use of ‘smart’ digital tools could lead to fewer teachers.

One thing is certain: learning will be shaken up. A such, a new discipline is emerging: education in the functioning and use of AI, such as writing clear and unbiased requests (the famous 'prompts'). AI could also promote collaborative learning – by facilitating the formation of communities or working groups – or replace end of year exams with a continuous, fairer assessment of students, thanks to progress tracking systems. Beyond that, personalised companions could accompany individuals even after they start working, for lifelong learning.

Finally, AI invites us to rethink educational practices by focusing on critical thinking rather than memorisation and assessment based on reasoning rather than on results. The most optimistic even predict that AI will help develop some of the noblest human qualities: critical thinking, sensitivity, imagination, and intuition. But to do this, we will have to teach everyone how to use AI wisely: by freeing ourselves from – and not by locking ourselves into – a reproduction of the world.

What impact on the brain?

Are students' thinking skills at risk of atrophying as they are delegated to machines? According to some researchers, this is a myth as they have not observed any deterioration in student performance, but rather increased cognitive flexibility. For them, delegating tasks to AI will simply change the way in which we use our brain in favour of critical thinking and reflection. However, other researchers are concerned that these tools could format our thinking by short-circuiting the learning process and offering standard solutions, as with autocomplete suggestions. Here too, everything will depend on uses and how they are included in teaching.

Emotions and real time monitoring

Chinese schools already use cameras, microphones, and physiological sensors to analyse students' emotions, detect attention lapses, and inform the teacher and parents of them. However, this dystopian phenomenon is not unique to China: emotional monitoring software is increasingly used in educational contexts, sometimes integrated into online tutors. In the USA, SpotterEDU was tested in several universities, sparking strong criticism. The idea was to monitor lesson attendance and send automatic emails to teachers or administration if a student was late or absent.