Medical cannabis: what hopes?

Now that several countries have opened the door to the therapeutic use of cannabis, we review the latest findings on the plant’s modes of action and the illnesses whose symptoms it can relieve.

Enquête de Marina Julienne - Published on , updated on

Banned for around a hundred years because of its psychoactive effects, cannabis is making a big comeback as part of the medical establishment's drugs arsenal. By carefully studying this plant, scientists have now identified the substance so highly prized by cannabis users, THC (delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol), distinguishing this from the many other cannabinoids it contains (in particular CDB, or cannabidiol), the therapeutic effects of which are only now starting to be understood. Research is taking place everywhere to find out how these substances work, to grow varieties of cannabis best suited to different pathologies and even develop drugs derived from the cannabinoids it contains. From relieving pain to potentially treating certain cancers, the possibilities are vast, but as yet few clinical trials have been carried out. Not prepared to wait for the experimental results to come in, many patients with serious illnesses are self-medicating, in most cases hoping to benefit from the analgesic and nausea-supressing effects of these substances. Will the hitherto unknown properties of cannabis one day put it firmly among the ranks of useful drugs? Or will its status as a recreational drug prevent it from being used more generally in medical treatments?

In France, medical forms of cannabis are legal but not commercially available

Sativex – a blend of THC and CBD in spray form produced for multiple sclerosis sufferers – is the only medicine containing cannabis to have been granted a marketing authorisation in France (in 2014). But it is still not commercially available because no agreement has been reached between its manufacturer, Almirall, and the French government. Patients are therefore forced to buy it abroad at an inflated price. Three other drugs are available, providing a doctor applies for a temporary authorisation of use for a named patient (as a one-off procedure): Marinol (THC) and Cesamet (THC), used to relieve pain caused by chemotherapy, and Epidiolex (CBD) used to treat certain types of epilepsy.

Therapeutic properties

Cannabis is chiefly used to relieve pain caused by certain serious diseases such as multiple sclerosis, AIDS and cancer.

This plant is not just a drug. It contains a large number of cannabinoids which have therapeutic effects. In countries where it has been legalised, it can be consumed in its natural state (as an oil or as herbal cannabis) or in the form of a drug (a spray, capsule or tablet) to relieve pain caused by certain diseases such as multiple sclerosis, AIDS and cancer. In France, cannabis is classed as a narcotic (similar to cocaine and heroin) because of the mind- and behaviour-altering psychoactive substance it contains: THC, or delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol. For this reason, it is illegal to grow and consume cannabis in France. However, although the varieties sold for recreational use can contain up to 20% THC, other varieties are characterised by their very low THC content and above all by the presence of another cannabinoid, CBD (cannabidiol), which has advantageous therapeutic effects (mainly calming and anti-inflammatory) and is not psychoactive. French law permits the cultivation of these varieties of cannabis containing less than 0.2% THC. But there's a catch: only the seeds and stems may be used, which makes it of interest to manufacturers (in the textiles and building industries for example) but less so to the medical field, because the cannabinoids are extracted from the flowers. As a result, it is not easy to get hold of these varieties for therapeutic purposes. Despite a severe warning issued by Mildeca (1), French suppliers who have been selling cannabis containing less than 0.2% THC continue, for now, to source their supplies from countries where the law governing the growing of hemp is more permissive, such as Switzerland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

(1) Mildeca: Mission interministérielle contre les drogues et les conduites addictives (Interministerial Mission for the Control of Addictive Drugs and Behaviours).

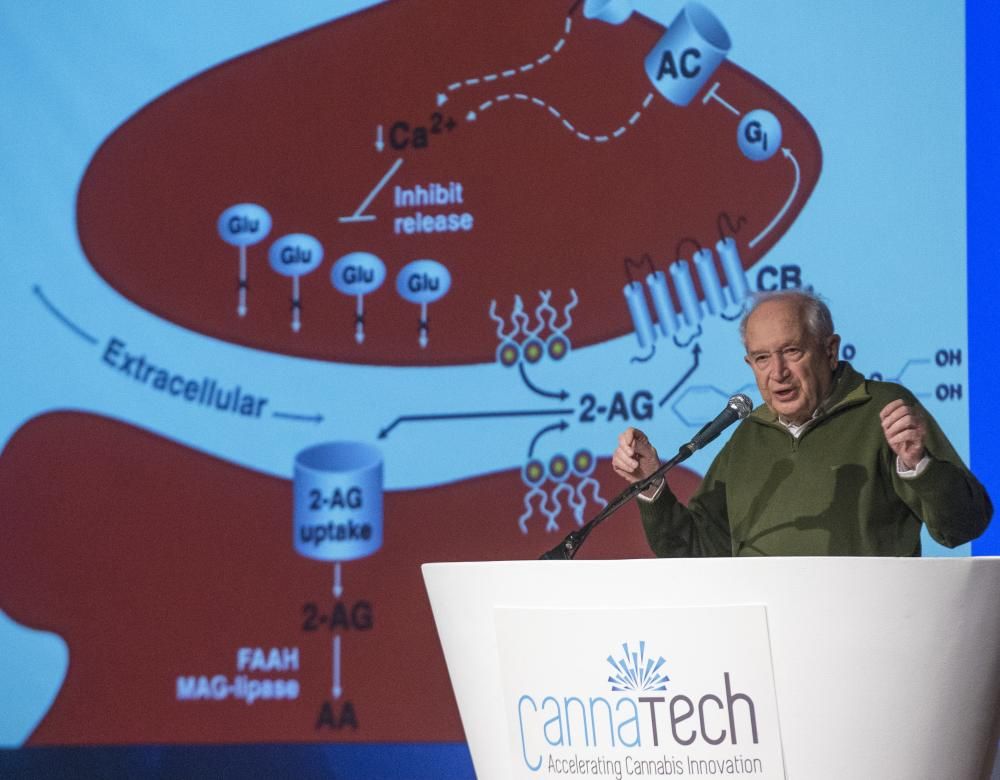

The 'father' of cannabis research

In 1964, the Israeli chemist Raphael Mechoulam isolated the main psychoactive agent in marijuana (herbal cannabis), THC (delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol), making him world-famous. He observed that it produced very different effects in different individuals and doses, but was unable to explain how THC works. In the mid-1980s, an American research team did: THC attaches to receptors in the central nervous system that normally connect with molecules made in the body called endocannabinoids. In 1992, the same Israeli team isolated the first of these molecules, anandamide, which is produced in response to a pain signal.

Patient experimentation

Some patients are trying out the therapeutic effects of cannabis on themselves and sharing their experiences on social media.

Our scientific understanding of cannabis may still be incomplete, but lots of patients are already using it. Even in countries where medical cannabis is authorised, doctors prescribing it have little information at their disposal apart from the trials carried out by the pharmaceutical laboratories that market these products. These misgivings aside, we do know about the composition of the main species of cannabis. For example, the species Indica contains a high concentration of THC (the psychoactive substance) and small amounts of CBD (cannabidiol); in Sativa the proportions are the other way around; Ruderalis, on the other hand, contains almost no THC. Another problem is that the efficacy of these products varies greatly depending on their origin, their method of consumption (by inhalation, vaporisation or ingestion) and the individual concerned. In practice, some users are experimenting on themselves to investigate the effects of cannabis and sometimes share on social media their findings regarding the supposed efficacy of different varieties for different indications. This makes it an unreliable source of information but one which can be useful to patients. For their part, associations such as the Francophone Union for Cannabinoids in Medicine are monitoring the medical applications of cannabis, identifying the most reliable trials and helping to distribute publications to inform patients and doctors (1). All in all, there is a certain amount of empirical evidence supporting the therapeutic use of cannabis. But it is not always easy to maintain a clear dividing line between those who are trying to promote the medical use of cannabis and those in favour of legalising cannabis for non-medical reasons.

(1) For example Chanvre en médecine by Dr Franjo Grotenhermen (Édition Solanacée, 2017)

Quality control, a public health issue!

There are many ways of ingesting cannabis for medical use. It can be smoked, inhaled, vaporised, taken in capsule or pill form, and more. A spray, one of the most widely used forms, is a way of evaporating the cannabinoids without burning plant material, which means that the patient does not ingest the carbon monoxide, tar and other toxins present in smoke. Now that the quality of the cannabis used has become an important medical issue, various companies market kits that enable users to check the composition of different treatments derived from the plant.

The first clinical trials

The administration of cannabis to patients in clinical trials is only in its early stages.

The main way that research laboratories are investigating the therapeutic properties of cannabis is in animal and human cells. So far, there have been few clinical trials involving patients. The efficacy of Sativex was demonstrated in a trial published in 2014 in patients with neuropathic pain. One hundred and twenty-eight patients were given a mixture of THC and CBD (delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol) in spray form, in addition to their conventional therapy, and 118 were given a placebo. The patients receiving the active substances were found to have a significant reduction in pain and an improvement in sleep quality. In the treatment of cancer, in 2018 the Canadian company Tetra Bio-Pharma is beginning phase-three clinical trials in 946 patients with terminal cancer using PPP001, a mixture of THC and CBD for inhalation. The objective is to provide pain relief for these patients, in whom morphine is no longer effective. Another example is Epidiolex (pure CBD), developed by GW Pharmaceuticals, which is being used to treat some forms of epilepsy and has already been used in a number of trials. The most recent of these involved 120 patients (children and young adults aged 2 to 18 years) suffering from a rare and severe form of epilepsy known as Dravet syndrome. This trial resulted in a 39% mean monthly reduction in fits compared to 13% in the placebo group. The drug is already authorised in France and could soon be authorised by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) in the US.

In search of the right plant

More and more laboratories around the world are working to develop new varieties of medical cannabis and new combinations of cannabinoids. These include Phytoplant in Spain, Bedrocan in the Netherlands, GW Pharmaceuticals in the UK and Insys Therapeutics in the US. And with around a hundred cannabinoids in each plant, these specialists have plenty of scope for innovation! The aim is to find the most effective variety and the best dose for each pathology.

The future: treating cancer with cannabidiol?

Laboratory research into CBD gives reason to hope that it might one day be a new way of treating cancer.

The unexpected discovery ten years ago that cannabis was able to bring about the 'suicide' of cancerous cells in mice (see video) was the cause of a great new hope. It has led to numerous scientists all over the world working on the effects of cannabis in treating cancer and metastases. Scientists such as Frenchman Pierre-Yves Desprez, who works at the California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco and who, with his American colleague Sean McAllister, discovered that CBD (cannabidiol) inactivates the ID-1 gene, which is responsible for the migration of metastases around the body. "CBD may therefore be effective in all cancers in which the ID-1 gene plays an active role (breast, brain and prostate cancer, among others) by preventing the migration of cancerous cells." After these results were published in 2007 (1), patients receiving chemotherapy immediately began taking CBD, and this appears to have improved the potential of their drug treatment. "We are now looking at the extent to which it may be possible to reduce chemotherapy if CBD is administered," says Pierre-Yves Desprez. "But so far this has all been tested in animals or in human cells in culture, and not yet in patients." Could the CBD in cannabis be the constituent that has all the benefits and no risk of addiction or psychoactive effects? Many hope that it will prove to be the medical Holy Grail. "But beware of regarding it as a miracle cure. Selecting the right molecules and dose are very important," warns Pierre-Yves Desprez.

(1) Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, November 2007

State-controlled drugs?

The Bedrocan plant in the Netherlands is the main supplier of medical cannabis in Europe, marketing five varieties of flowers compressed into granule form or administered as a spray. These products are already being distributed for compassionate use in some European pharmacies (but not in France), mainly for treating cancer and AIDS patients. In Italy, a pharmaceutical plant run by the army supplies pharmacies with the country's first medical variety used to treat pain (FM2), which contains 6% THC (delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol) and 8% CBD (cannabidiol).

A market potential of billions of euros

Thought to be very lucrative, the medical cannabis market is booming.

In Europe, the Czech Republic is the leading producer of CBD. Thirty-six billion euros a year: that's what the European therapeutic cannabis market could be worth in five years' time, according to a study by the London-based group Prohibition Partners. In addition to the sale of varieties containing THC (the psychoactive product), a lucrative market is emerging for cannabidiol (CBD), a substance that has no psychotropic effects and is not addictive. Products containing CBD are now everywhere, in the form of capsules, infusions, an e-cigarette liquid, cosmetic balms, edible oils and more. In Europe, the Czech Republic has become the leading producer of CBD. In terms of selecting appropriate varieties, cultivation and sale, the prospects for the medical cannabis market are bright. As a result, some regions have identified a tremendous opportunity for growth. Greece recently legalised medical cannabis, promoting the country's climate, which is very favourable to the cultivation of the plant, and estimating a turnover of between 1.5 and 2 billion euros. France is the leading European producer and the second biggest producer worldwide (after China) of industrial hemp. But before medical cannabis can be grown here, French law will have to be changed, because it currently does not permit the commercialisation of hemp flowers, which is where the CBD is found.