NFTs: fashion trend or genuine innovation?

Does the growing popularity of NFTs reflect a mere fashion trend or does it mark the emergence of a new generation of certified transactions?

Investigation by Pierre-Yves Bocquet - Published on

NFTs or non-fungible tokens are today’s digital prodigies. Sales rocketed in 2021, totalling tens of billions of dollars and raising fears of a speculative bubble. But some artists are taking advantage of the opportunity for the time being. They include French photographer Yann Arthus-Bertrand, who produced and sold his first NFT to aid Ukraine. And the first metaverses are beginning to market virtual land in NFT form. Another example comes from the Roland-Garros tournament, which is selling NFTs. Buyers enter draws in which they can win tennis-related prizes. So what is the story of those curious initials? Are NFTs just a gimmick or a sound financial investment? Is the enthusiasm for them justified? An exploration of this rather mysterious world…

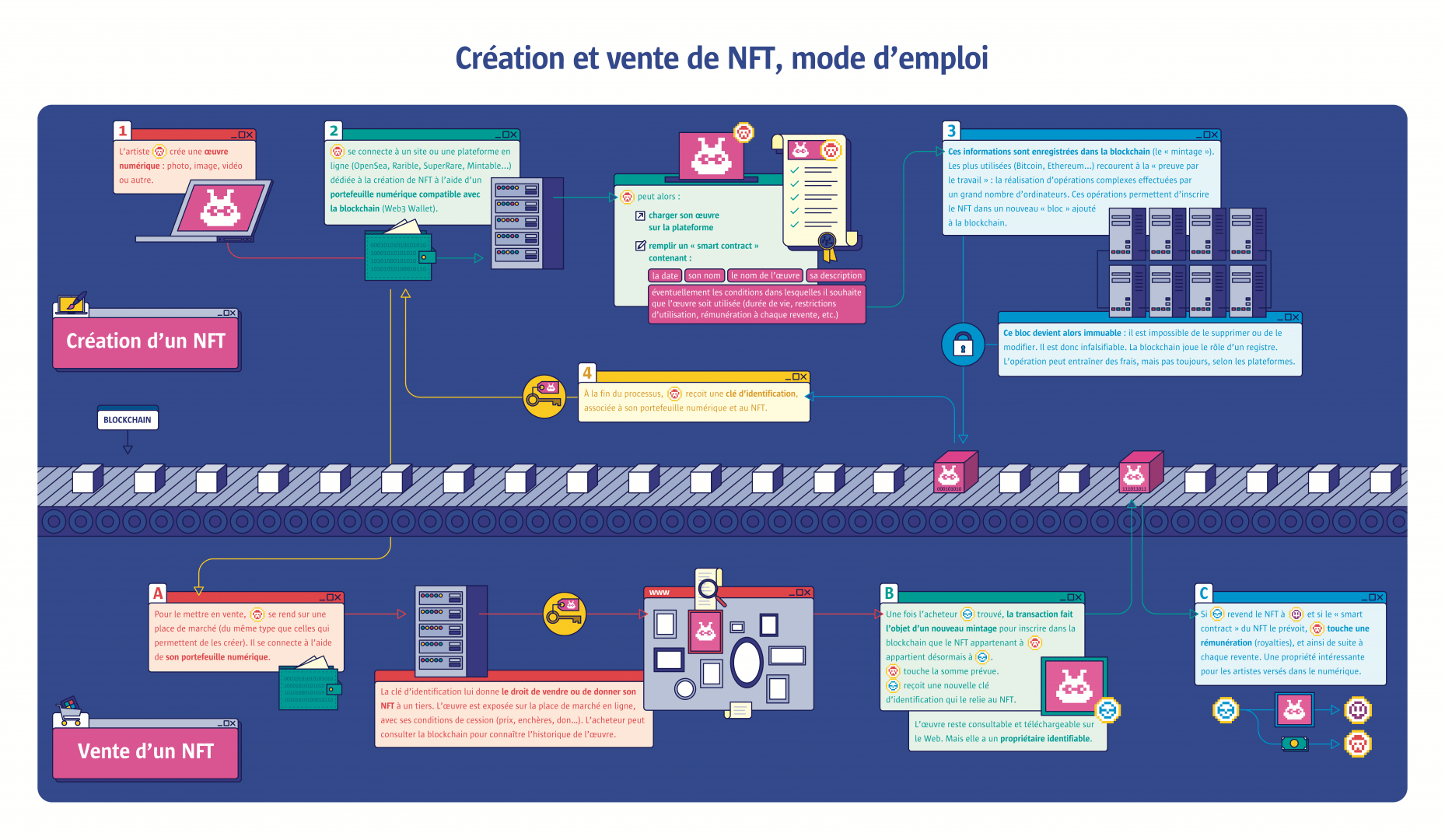

The blockchain behind NFTs

An NFT is a digital certificate that uses blockchain technology to guarantee its reliability, transparency and traceability.

NFT stands for non-fungible token, a digital property certificate linking an item, usually a virtual one (e.g. an artwork, document or video), to its owner. The asset is recorded in a digital registry using blockchain, an information storage and transmission technology introduced in 2008. Blockchains have previously been used to ensure cryptocurrency security. Not centrally controlled, the database is made up of blocks (basic units) that are added to each other to form a “chain”. Every time a new block is added, the data are authenticated by a decentralised computer network running algorithms. Each transaction is validated before being recorded in the blockchain. Encrypted and forgery-proof, the information can be authenticated by all the network’s users. The inclusion of a “token” in the blockchain enables the verification of its existence and date of creation, ensures its traceability and records its content (a given virtual object belongs to a given person). The adjective “fungible” refers to the interchangeable nature of an asset. For instance, a 1-euro coin is worth the same as any other. So it is “fungible”, only having value because of its function, not as an object in itself (except for collector coins). Conversely, an NFT that permanently links a digital item to its owner is seen as “non-fungible”. It is unique, identifiable and traceable, and has a specific, innate value.

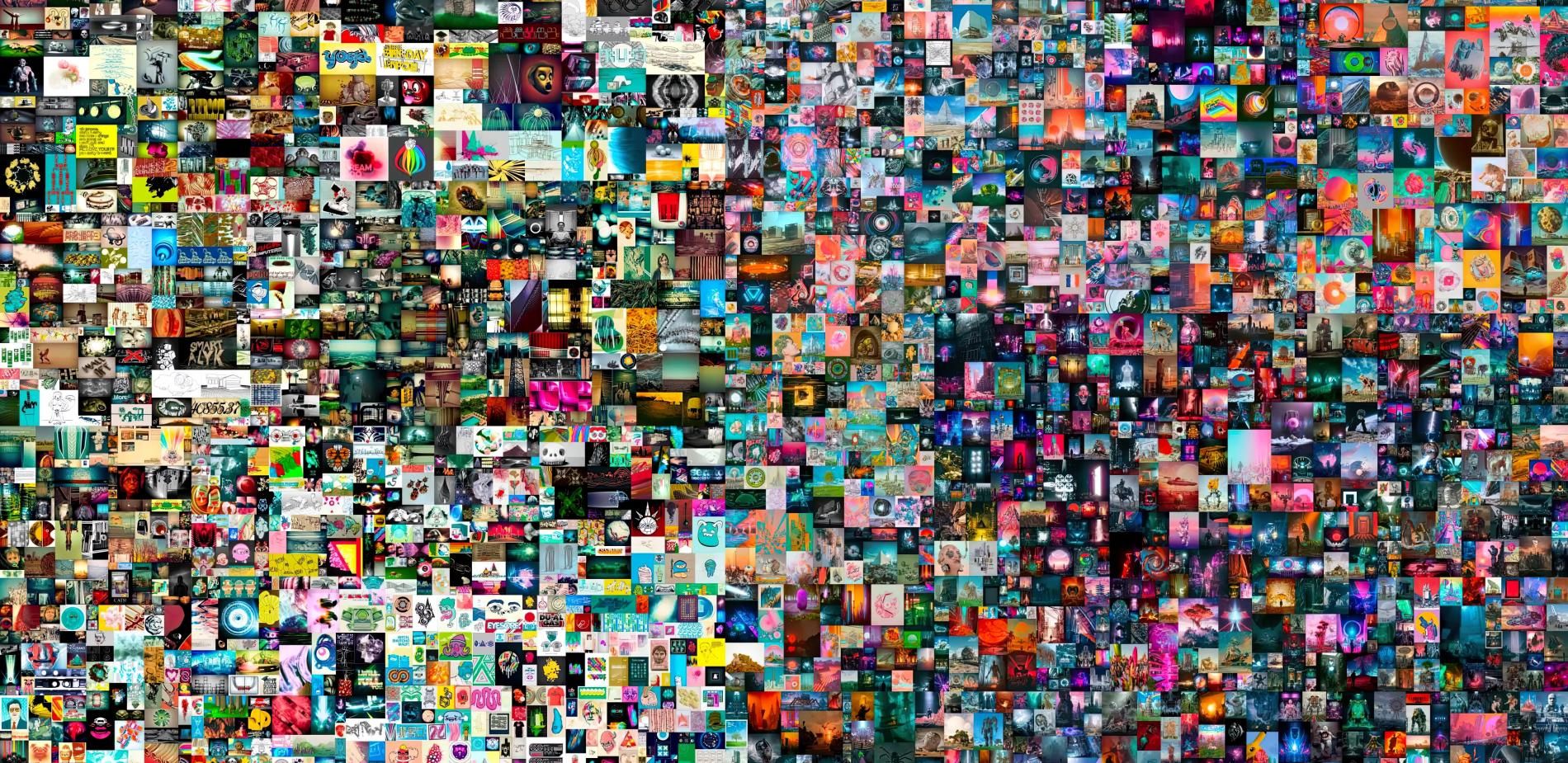

Record sales of NFTs

The NFT of the first tweet ever (shown here at auction) sold for 3 million dollars in March 2021. But two years later, it only attracted a maximum bid of 30,000 dollars, despite being put up for sale a number of times. That is a very different figure to the record sum fetched by the work Everydays: the First 5,000 Days by American digital artist Beeple, which sold for 69.3 million dollars at Christie’s New York, again in March 2021. Everydays is the most expensive NFT sold to date and, for a few months, was also the third most expensive work sold by a living artist.

Pioneering digital artists

Artists were soon excited by the potential of NFTs, which enable them to guarantee the rarity of a digital item and receive royalties.

Artists were the first to embrace NFTs, which allow them to certify a degree of rarity or even the uniqueness of a digital work (for instance a photo, image or video). Digital creations are usually at a disadvantage compared to physical objects such as paintings or sculptures: they are by nature easy to reproduce with a simple “copy-and-paste” operation, and can be shared on the Web. But when an artist secures their work with an NFT, they turn it into a unique object rather than just a simple copy. The NFT provides the article with a guarantee of origin comparable to a certificate of authenticity for a material work. The operation is free or inexpensive and allows them to control the work’s distribution, together with the royalties they will receive as long as it remains in copyright. That benefit has led many artists to welcome NFT technology, including the French-Algerian plastic artist Neïl Beloufa. Then various industries see NFTs as new, exclusive products to be marketed. For example, videogame publishers can sell players functions and accessories to improve the appearance and power of their avatars. In high-level sport, certain licensers sell content in NFT form, including the USA’s NBA, which markets highlights from League matches. Finally, movie producers such as 20th Century Studios (Fox) and Disney are also hoping to sell branded NFT merchandise: characters, movies or cult series. A new merchandising successor to the classics that proved so valuable to the “Star Wars” brand.

A protest NFT

Stay Free by the British artist Platon shows a portrait of Edward Snowden, the whistle-blower who became famous when he denounced the surveillance programmes of the US intelligence body which employed him, the NSA. The Stay Free image is formed by American legal rulings on the illegality of such practices, handed down following the disclosures of the former agent. The NFT sold for nearly 5 million dollars in April 2021. The sale was approved by Edward Snowden and the funds used to support whistle-blowers and press freedom.

Just a speculative bubble?

The NFT market took off in 2021, boosted by the involvement of artists and the potential profits for investors.

2021 saw a boom in the sales of art NFTs, which sometimes fetched huge sums. Indeed, the world NFT market totalled nearly 41 billion dollars in 2021, compared to 250 million dollars the previous year. So was there a risk of a speculative bubble bursting? From the start, NFTs have suffered from their technical association with cryptocurrencies that are also based on the blockchain, such as the Bitcoin, whose value has soared over the last few years but remains very volatile. Some see NFTs as a new investment promising high profits and even resort to selling NFTs for items to which they do not have the rights! However, the bubble already seems to be leaking. Indeed, the NFT market could be “normalised” in 2022, with first-quarter sales of under 8 billion dollars. In any case, the future of NFTs still depends on the reply to a basic question: what is their true legal and fiscal value? As is often the case, the law has lagged behind the technology and the response to the issue is still under discussion. France’s 2022 Finance Law should establish tax regulations for digital assets, including cryptocurrencies and NFTs. Then a European Parliament bill for the regulation of such property could become law by 2024. The resulting legal framework will play a very important part in helping the market to achieve a kind of stability and govern the use of NFTs in other domains, especially professions that are very reliant on certification (solicitors, registrars, barristers, etc.) and other sensitive areas, such as the protection of personal health data.

Science in the age of the NFT

NFTs related to the work of distinguished scientists are beginning to fetch high prices.

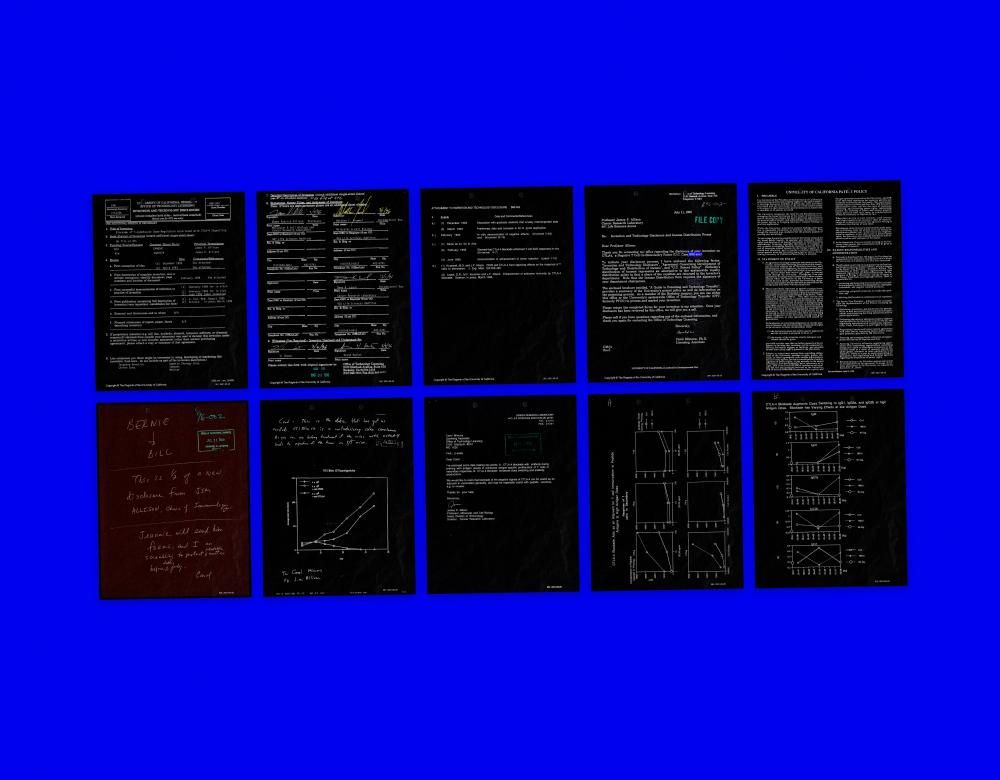

A new way of funding research? Scientists are also taking an interest in NFTs. They are now a focus of research into digital technology in the field of human sciences of course, but also because they see NFTs as a new way of promoting their work and funding new research, at least in the USA for now. More and more of these NFTs have been created over the last few months. The renowned University of California, Berkeley auctioned an NFT based on the research of one of its foremost scientists, the oncologist James Allison, winner of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Medicine. The NFT, which includes documents and research notes written by the scientist himself, sold for more than 50,000 dollars on 8 June 2021. Given the success of the initiative, the university may repeat the exercise with the work of Jennifer Doudna, who jointly won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with France’s Emmanuelle Charpentier for the development of a new genome-editing technique, Crispr-Cas9. In June 2021, IT expert Tim Berners-Lee, creator of the World Wide Web, sold NFTs featuring its source code at auction. The 5 million dollars raised were donated to charity. Finally, California’s RMDS Labs have announced the creation before the end of the year of the first NFT marketplace to enable scientists to monetise their work. But the thorny question of rights has not yet been settled. Does the research belong to the scientist or the organisation they work for?

A piece of science history

Entitled The Fourth Pillar, this work presents documents personally written by James Allison, winner of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work on immunology. His research has led to the development of immunotherapy, seen as the fourth pillar in the battle against cancer after surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The NFT sold for more than 50,000 dollars at auction on June 8, 2021 with the approval of the scientist. The money went to a Berkeley research fund.

Metaverses, the future of NFTs?

Interaction in a virtual world and the purchase of assets in the form of NFTs: that is the future promised by Web3, a new generation of Internet structure.

What better place than a virtual world to purchase, sell and use virtual items? Today, there are more and more metaverse projects. So what are metaverses? 3D virtual worlds in which an avatar—a digital double—can talk, trade or play with other users, using a virtual-reality headset or not. Together, metaverses and NFTs based on the blockchain will shape the future of the Internet, with what we call Web3 (Web 2.0 referred to the “social” or “participatory” Internet). The most widely publicised metaverse projects are those planned by Meta (Facebook) and Microsoft, but there are others too, some of which—such as “The Sandbox”—already manage the purchase and sale of NFTs. In April last, the American corporation specialising in NFTs Yuga Labs sold 320 million dollars’ worth of lots of land in its “Otherside” metaverse. Buyers will be able to personalise their property and perhaps cash in on it through trading or advertising if they attract a lot of visitors. A number of brands have already joined both these metaverses and the NFT market, especially luxury brands who see NFTs derived from their products as a way of forming “communities”. Even so, the metaverse future remains unclear. How many will there be? Will they be interconnected? Will people be prepared to wear headsets all the time? The technology is still in its infancy.

Close encounters in the metaverse

For the moment, concrete metaverse applications—for instance meetings between avatars—are still limited. But new applications are already emerging, suggesting a future increase in the use of NFTs to certify such transactions as the purchase of property in a virtual universes. Another example: in March 2022, the Decentraland metaverse organised the first “Metaverse Fashion Week”, enabling the public to buy pieces from the collections of Dolce & Gabbana and Estée Lauder in NFT form (to personalise avatars) or actual physical items.

Problematic energy consumption

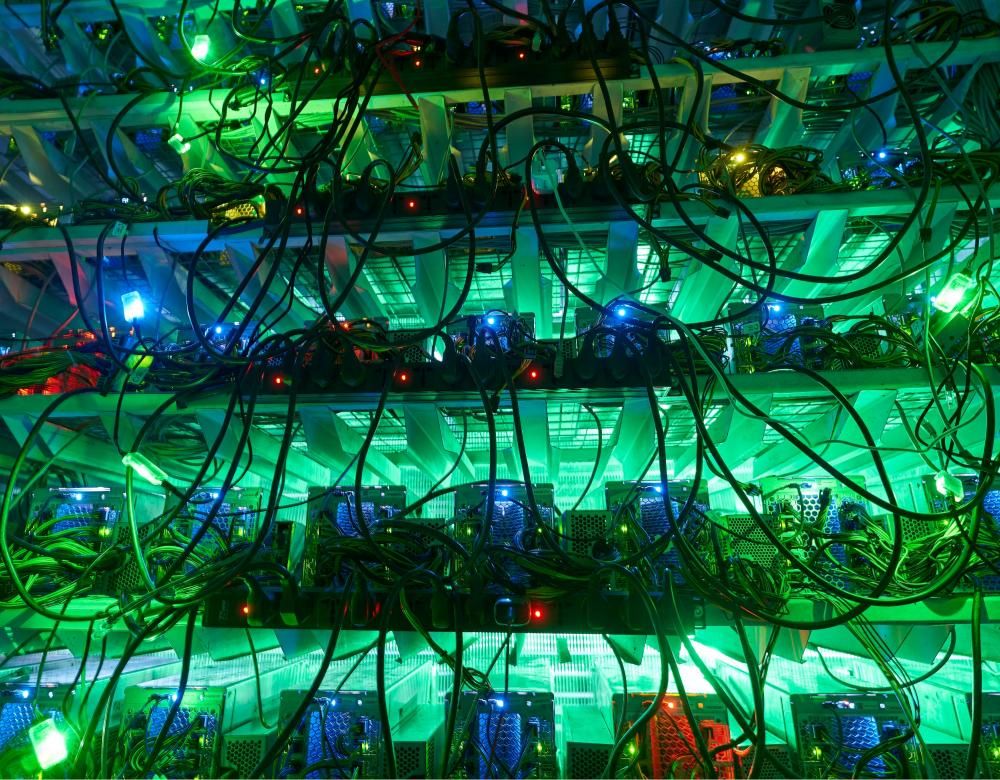

NFTs have a considerable carbon footprint because they rely on blockchains.

But new technologies could soon reduce it. NFTs employ the blockchain, a computer process used to produce them. Unfortunately, most blockchains are based on a “proof of workload” principle: whenever information is added, the data are deciphered and authenticated by thousands of computers that are networked to process cryptographic operations. The energy cost is high: the machines consume electricity (for their running and cooling) and the ecological cost depends on the type of energy used to generate that electricity. Around the world, the production of Bitcoins (using the same techniques as NFTs) is said to have consumed 80 to 130 TWh in 2021 according to the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), equivalent to nearly of a third of the energy produced by France’s nuclear-power industry over the same period (361 TWh). Indeed, the problem has led some ecologically-committed artists to boycott the production of NFTs related to their works. That said, some blockchains—such as Ethereum, which is the most widely used to create NFTs—are planning to use another method of ensuring data security: “proof of stake”. The technique is just as reliable, but requires fewer operations—and so less energy—than “proof of work”. Ethereum has announced that this transition will reduce its annual energy consumption by 99.95%, taking it down from the requirements of a small country to the needs of a town with a population of 2,000. But that change said to be imminent in May 2021 has been delayed.

The high energy consumption of digital farms

Blockchain production requires huge computing capacities, with devices made available in return for cryptocurrency credits. So individuals and companies have invested massively in equipment to create farms for “mining” (cryptocurrencies) or “minting” (NFTs). They obviously consume a great deal of energy, so they are responsible for very high CO2 emissions unless powered by renewable energy sources, such as solar panels. That was the idea behind the initiative launched in spring 2022 by billionaire Elon Musk (Tesla) to reduce the carbon footprint of his mining farms.