Placebos: what does science say?

At the heart of numerous controversies, placebos and the placebo effect constitute a new research field that far exceeds conventional drug evaluation.

Texts by Lise Barnéoud - Published on

At the heart of the current debate in France on homeopathy, the placebo and its corollary, the placebo effect, are the subject of many research studies. Some of the secrets of this psychological, sociological and biological phenomenon are beginning to emerge and imaging studies have even allowed us to objectify its action on the brain. But is recourse to placebos useful and legitimate? And if so, what place should medicine give it, in a country that already has a high rate of medical treatments prescriptions, be they pharmacologically active or not; given as well that there are often alternatives to these treatment (such as physical activity, healthier diets, psychological care or simply rest). Should the placebo effect – combined or not with taking pills – be used to reduce the dosage of medication, in particular for psychosomatic pathologies? All these questions remain a subject of controversy. The only certainty is that the famous maxim primum non nocere (“first, to do no harm”) must be the compass of any medical practice, especially when dealing with the most severe pathologies. And the need for effectiveness leads to prioritizing proven forms of treatment. Scientific studies are gradually helping to resolve the current questions.

And “the physician effect”?

That the physician’s most effective medication is the physician herself is a well-known phenomenon. Studies have shown (including a recent study by Inserm) (1), that the condition of patients improves faster when the physician shows empathy and engages in a positive explanatory approach. Physicians with negative approaches who do not provide this attention do not benefit from the “physician effect,” which may enhance a placebo effect or a real pharmacological effect when a drug is prescribed. This effect is one of the main ingredients of improvements due to so-called non-specific therapies. In and of itself, it accounts for recoveries in functional pathologies without major risks, especially in the context of so-called alternative medicine.

(1) C. Fauchon et coll., Scientific Reports (2019)

Divergences over definitions

Scientific literature on the subject is accumulating and yet there is no consensus about the definition of a placebo, no less the placebo effect.

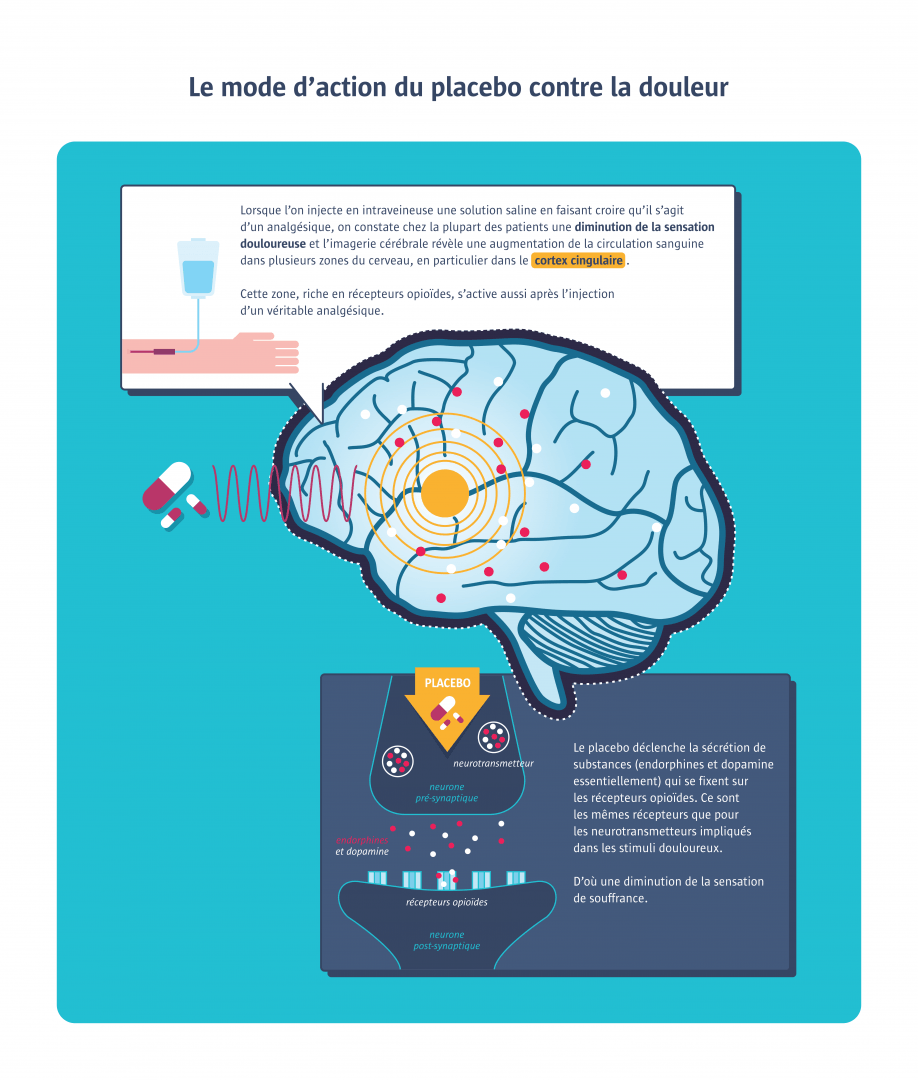

The word “placebo” (from the Latin verb for “to please”) appears in medical textbooks in the late 18th century. At the time, it was defined as “any medicine adapted more to please than to benefit the patient”. Pills containing water, sugar, starch, bread crumbs or saline were used. Few drugs rivalled it in efficacy. The placebo took on another dimension in the mid-20th century when it was first used in controlled clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of new pharmacological treatments. Representing the zero value of therapeutic effectiveness, it is defined as “a substance or procedure that has no therapeutic effect on the condition being treated”. There are two types of placebos: pure placebos, which have no pharmacological effect (e.g. water and sugar capsules), and impure placebos, which have pharmacological effect but not on the specific pathology being treated (e.g. vitamin C for a flu). As for the definition of the placebo effect, specialists are divided on the subject. For some, this effect refers to the improvements that come from taking a placebo. For others, it encompasses all improvements linked to the “therapeutic ritual” (physician, prescription, medical gesture, etc.) and the psychosocial context that surrounds the treatment. Based on the latest scientific publications, it now seems more accurate to speak of placebo effects in the plural, as the realities the term covers are multiple. Imaging studies confirm that several different pathways are activating from one placebo to another, and even from one patient to another.

Placebo surgery!?

In some cases, surgical procedures are no more effective than “placebo surgery,” which consists in simply making an incision in the skin without making any anatomical changes. This is the surprising conclusion of a meta-analysis of ten studies, eight of which failed to demonstrate the greater efficacy of actual operations (1). These included operations for osteoarthritis of the knee and forefoot, incontinence surgery, ENT surgery for sleep apnoea, and neurosurgery for Parkinson’s disease. These findings are probably related to the high expectations that patients have from surgery, which is considered particularly effective.

(1) Probst P. et al., Medicine, 2016

Can the placebo effect be objectively measured?

It is extremely difficult to distinguish between the various factors involved in successful treatments.

This is one of the main challenges of placebo research. The ideal methodology for evaluating drug efficacy is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. In other words, the comparison of several groups of patients when neither the participants nor the experimenters know the nature of the treatment administered. This approach minimizes the psychological factors that could influence results, in particular the expectation of benefits from a pharmacological treatment. Any attempt to distinguish and measure the different components that participate in a successful treatment – the drug’s pharmacological effect, the placebo effect, the physician effect, the disease’s natural course, and so on – would require comparing four groups: one receiving a medication; one receiving a placebo; one benefiting only from a medical consultation; and a control group receiving no treatment or consultation. But several problems arise. It is impossible to set up a double-blind trial for a group receiving no treatment or consultation. The very fact of being observed in a medical study influences patients, who may tend to pay more attention to themselves and be more motivated. This is called the “Hawthorne effect.” In addition, it is medically unethical to conduct studies giving patients placebos when a treatment exists that is deemed effective. Ultimately, it is difficult to measure objectively exactly what in the therapeutic process is due to the placebo effect.

The uncertainty of numerical results

Findings in studies on placebos are hard to reproduce and present numerous biases.

One often hears that the placebo effect works in one out of three cases. Is this really true? This estimate refers to the 1955 study of an American anaesthetist who, for lack of morphine, relieved the wounded during the war by injecting a plain saline solution. The problem is that, at the time, any relief or cure not due to drug taking was attributed to the placebo effect, without the natural evolution of symptoms being taken into account. More recent studies, with control groups receiving neither treatment nor placebos, demonstrate less efficacy. But the findings differ enormously from one study to another. Thus, the efficacy of placebos on pain varies from 5 to 65% from one clinical trial to the next (1). After reviewing more than 200 publications on 60 pathologies, Danish researchers estimated that 92% of the studies presented significant methodological bias, in particular reporting bias, as many of these studies were based solely on patient-reported data (2). In general, positive effects are found against pain, nausea, phobias, coughing, shortness of breath and irritable bowel syndrome. But several studies (3) also report objective physiological improvements with placebos in treating cardiac rhythm disorders, or the release of dopamine in patients with Parkinson’s disease. In contrast, the placebo response is zero in Alzheimer's disease, cancer or obesity.

1. Zubieta et al, Ann N Y Acad Sci., 2009

2. Cochrane Systematic Review, 2010

3. Petrie KJ et al.; Annual Review of Psychology, 2019

Am I a placebo responder?

Some people seem to be more responsive to placebos. This may be due to personality traits (such as optimism or level of empathy), the person’s experience, or certain genetic traits (such as genes involved in the dopaminergic or opioid system). A recent imaging study of 63 chronic back pain patients suggests that it may even be possible to predict individual response levels by looking at brain structures, particularly inside the prefrontal cortex (1). In March 2019, a review of existing literature also suggested that it is easier to elicit a placebo response in men than in women (2).

1. E. Vachon-Presseau et al., Nature Communications, 2018

2. P. Enck and S. Klosterhalfen, Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2019

What about patient information?

Several studies since 2010 show that a placebo effect can be elicited without deception.

Until recently, it was thought that the placebo effect only worked if patients didn’t know they were taking one. This meant misleading patients about what they were being prescribed, and therefore proceeding without their informed consent, which raised an important ethical issue. However, a study published in 2018 on 46 people with allergic rhinitis seems to indicate that the symptoms improve identically when given a placebo with or without information, compared to the group without placebo (1). “A result that is probably due to conditioning, and the fact that we’re used to swallowing pills,” according to Michael Schaefer, professor of the Medical School of Berlin and leading author of the study. If this is true, why not be totally open? A dozen recent studies on patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome, back pain, or episodic migraines suggest that placebo treatments elicit an effect even when patients are clearly informed of the inert nature of the substance they are taking. This is the so-called open-label placebo concept. Depending on the study, between 15 and 60% of patients receiving open-label placebos report an improvement of their symptoms (2), a very wide range of variance but at any rate a significantly higher percentage than the group of patients receiving no treatment. These results may be due to the power of positive suggestions: even if patients know that the substance is inert, explanations from the physicians about how the placebo effect works on their symptoms may have a decisive impact.

1. Schaefer M. et al., PlosOne, 2018

2. Ted Kaptchuk and Franklin Miller, BMJ, 2018

Acupuncture under examination

Since 1975, a variety of studies have tried to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture compared to a placebo treatment by needling points outside traditional meridians, using telescopic (retractable) needles that don’t penetrate the skin, or LEDs simulating laser acupuncture (1). Most research conducted in Asia has tended to show the value of acupuncture, as in a recent study in China of 400 patients with angina (2). In the West, on the other hand, the majority of meta-analyses have failed to show the greater efficacy of acupuncture over placebos (3). Thus this ancestral practice remains a controversial form of treatment.

Sources :

1. Yang Y et al., Acupunct Med., 2016 ; Xiang Y et al., J Pain Res., 2017

2. Zhao L., Jama, July 2019

3. With rare exceptions, as, for example, for migraines or musculoskeletal disorders. Vickers AJ et al., J. Pain, 2018

A role in the treatment arsenal?

According to some physicians, placebos can sometimes be useful as a complement to conventional treatments.

From a scientific standpoint, treatments that have not proven effective have no place in medicine. Obviously, placebos cannot take the place of a proven treatment or delay its implementation. Yet some physicians are arguing that it should be regarded as a therapeutic ally, one tool among others in a treatment plan. This naturally supposes that placebos have demonstrated a greater efficacy than no treatment at all and that they present no dangerous side effects, explains Rémy Boussageon, professor of Universités de Médecine Générale (1). As long as the physician is also honest with the patients and informs them of the nature of the placebo, says Ted Kaptchuk, professor at Harvard Medical School, noting that one of the impediments to such use is that it goes against the training and medical standards of doctors prescribing drugs with recognized biochemical properties to achieve a specific therapeutic benefit (2). In practice, a study of 1,200 participating internists and rheumatologists in the United States shows that more than half reported prescribing placebos, for the most part impure placebos (such as vitamin C for the flu); the use of pure placebos remaining rare (2 to 3%) (3).

1. L’efficacité thérapeutique. Objectivité curative et effet placebo, thesis Lyon-3, 2010

2. Ted Kaptchuk and Franklin Miller, BMJ, 2018

3. JC Tilburt et al., BMJ, 2008

Placebo by proxy effect

Caregivers reassure by showing empathy and create an environment conducive to healing. This could explain why the placebo effect is observed even in domestic animals or infants, sensitive to the emotions of those around them. A study of 119 children under the age of 4 suffering from a cough showed greater improvement for the placebo group than for the group receiving no treatment (1). This is called the placebo by proxy effect: the behaviour of the parents who believe in the effectiveness of the cough syrup induces a placebo effect in the child.

IM Paul et al., Jama Pediatr, 2014

Homeopathy in the hot seat

‘Homeopathic medication has not demonstrated sufficient efficacy to justify reimbursement.’ This was the opinion announced on 28 June 2019 by France’s National Authority for Health, after evaluating more than 1,000 studies of 1,163 homeopathic remedies. But the impact on health expenditures of the decision to stop reimbursement – scheduled to take effect in 2021 – remains controversial. Advocates of homeopathy call for further studies, arguing that the evaluation of ‘rendered medical services’ cannot be limited to testing the pharmacological efficacy of homeopathic granules. For radical opponents of the treatment, it should not be taught in medical school and doctors should clearly inform patients that any improvements are due solely to a placebo effect.

Nocebo, the dark side of placebos

Whereas the placebo (Latin for “I will please”) may produce a desirable effect, the nocebo (Latin for “I will harm”) is at the origin of undesirable symptoms.

The nocebo, first defined in 1961 (1), refers to the appearance of side effects unrelated to objective factors. It can be observed in reactions to a change from a brand-name drug to a generic drug or, more simply, in increases in blood pressure or heart rate during clinical visits, connected to what’s called the “white coat syndrome.” Another example: the symptoms experienced by “hypersensitive” individuals to electromagnetic waves in the absence of a scientifically established causal link; nevertheless, the French Agency for Health and Safety (ANSES) recommends continuing research with long-term follow-up studies (2). The nocebo effect also played a role in the recent “Levothyrox affair.” A new formulation of a thyroid hormone drug with a different excipient (coating the active ingredient), introduced in France in 2017, resulted in some patients complaining of cramps, headaches or dizziness. Was this the result of a nocebo effect? France's National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (ANSM) concluded that the new formulation was innocuous (3). However, in the case of a drug with such a narrow therapeutic margin – which means that the difference between effective and inappropriate doses is small – the change in excipient may have modified the dosage of the active ingredient ever so slightly, which may, in turn, have caused the undesirable effects. The ANSM is also focusing attention on the lack of information and support for patients, because the nocebo effect, like the placebo effect, is at the heart of the patient-doctor relationship.

1. Kennedy WP, Med World, 1961

2. Anses, March 2018 3. ANSM, June 2019