The new era of psychedelic therapies

LSD and hallucinogenic mushrooms help treat depression, addiction or end-of-life anxiety. This is the conclusion of recent studies that suggest a return to psychedelic therapies in psychiatry.

Une enquête de Mélissande Bry - Published on , updated on

The Great Comeback, 50 Years Later

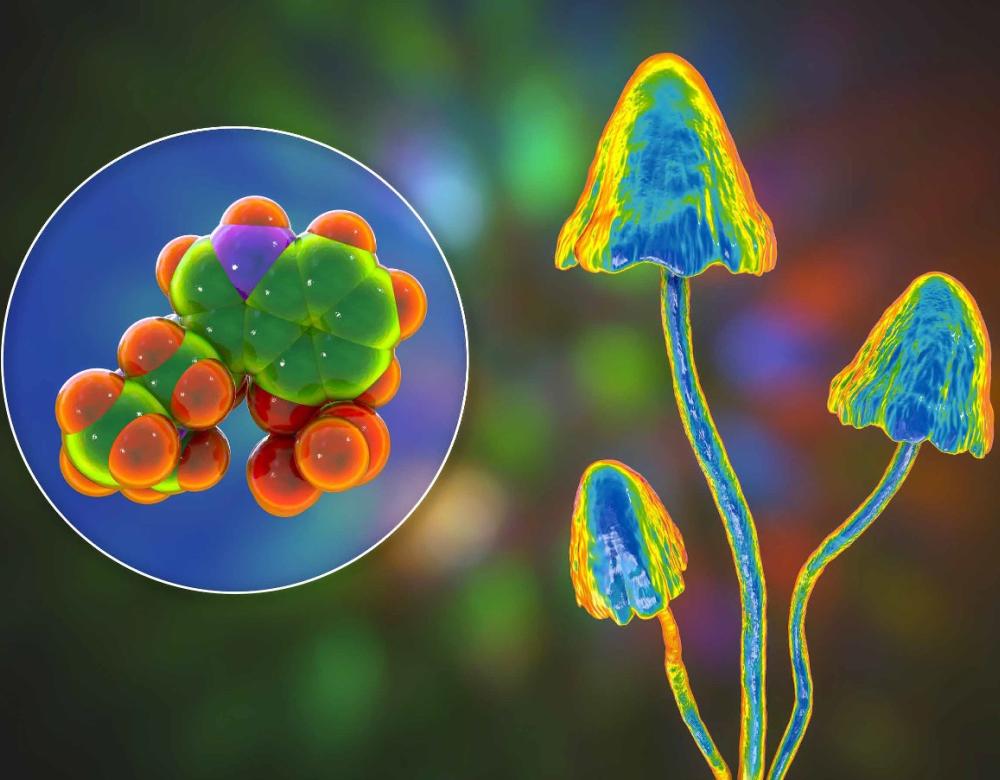

This is a pioneering study in France. In the summer of 2024, the Centre hospitalier Sainte-Anne in Paris launched the COMP006 clinical trial, evaluating the efficacy of psilocybin in the treatment of treatment-resistant depression. Psilocybin is the active compound in hallucinogenic mushrooms, known to trigger serious thought, perception and mood alterations. It may be surprising to think of these substances as medicine.

However, this is not a new idea. Psychedelics such as LSD, psilocybin and mescalin were studied broadly in the 1950s and 1960s; they were tested in the treatment of various psychiatric disorders, and these molecules produced promising results. But research was halted abruptly in the early 1970s. Due to their easily recognizable effects, psychedelics could not be tested under the new 'double-blind, placebo-controlled' standard.

At the same time, the counter-cultural hippie movement seized on these substances and rare, highly publicised scandals set off an unprecedented wave of moral panic. The scientific and cultural context had become unfavourable, and in 1971 the UN classified LSD and psilocybin as category-1 narcotics, a category covering most sensitive chemical substances.

Research on psychedelics resumed in the 2010s. During this period, clinical trials were performed on cancer patients with encouraging results. These studies marked the beginning of the rebirth of psychedelic therapies.

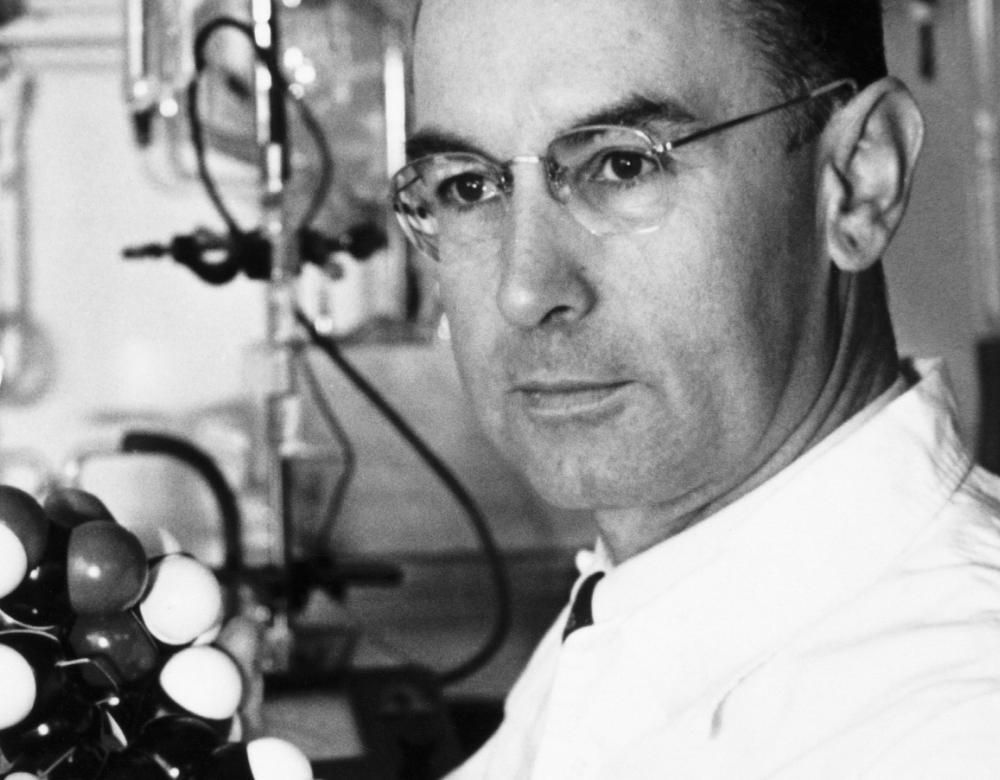

1943, a first cycling trip

LSD-25, or lysergic acid diethylamide, was synthesised for the first time in 1938 by the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann. Derived from the Claviceps purpurea fungus, LSD was used in pharmacological tests on blood pressure. As the results were inconclusive, the molecule was soon set aside. Five years later, on 19 April 1943, Hofmann voluntarily took a minute dose of LSD. He felt the effects as he was returning home by bike: anxiety, dizziness, laughter and hallucinations. Hofmann’s experience was known as the very first LSD trip in history, and marked the beginning of research into this molecule in the west.

From religious rituals to laboratory benches

Most clinical trials study the effects of psilocybin. Less stigmatised than LSD, it also has a shorter span of action: 4 to 6 hours (compared with 6 to 12 hours for LSD). The hallucinogenic mushrooms from which it is extracted were originally consumed at religious rituals in Mexico, such as Psilocybe mexicana, the best known of them, used by the Mazatecs. The French mycologist Roger Heim, director of the French Natural History Museum until 1965, was fascinated by their transcendent properties and freely consumed them himself. It was from samples grown at the Museum that Albert Hofmann, the father of LSD, isolated their active ingredient in 1958.

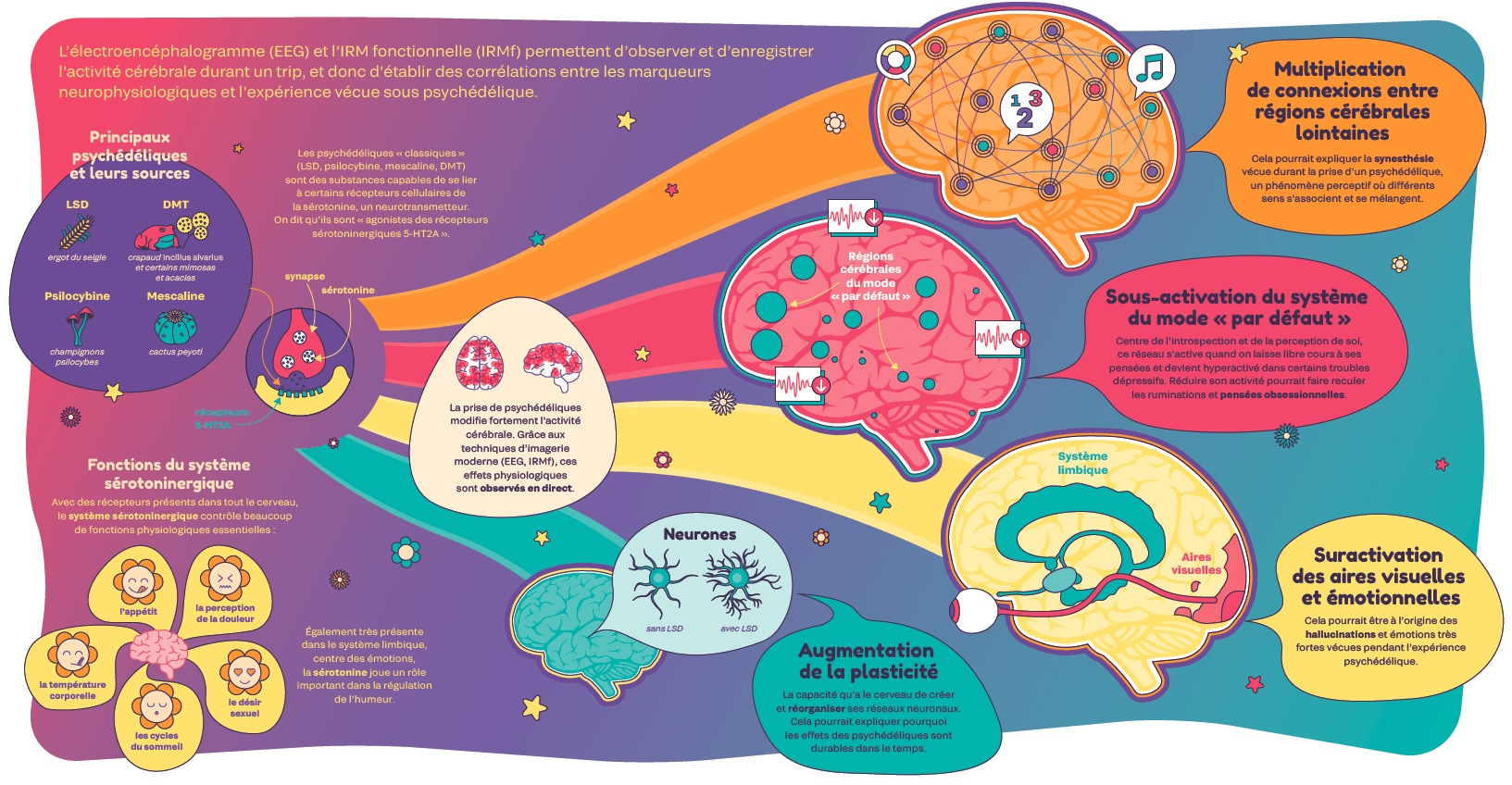

The brain on a trip

Electroencephalography (EEG) and functional MRI (fMRI) are used to observe and record brain activity during a trip, and thus to establish correlations between neurophysiological markers and experiences under psychedelics.

A solution for addiction and rumination

Recent studies have focused on treatment of major addiction disorders, depression and end-of-life anxiety. Indeed, it seems that psychedelics help to unravel repetitive and rigid thought patterns. For example, they may reduce cravings, the overwhelming urges commonly experienced by addicted individuals, very common in patients suffering from depression. This ability to calm the mind and make it more flexible could also be useful in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

On a different note, psychedelics could provide psychological relief to patients suffering from incurable diseases. It is difficult to treat the loss of purpose that develops following the announcement of a fatal diagnosis. In a historic study published in 2016, a team from Johns Hopkins University tested psilocybin on cancer patients. And it produced surprising results: with a single dose, scientists found a lasting reduction in anxiety, increased quality of life and acceptance of death in participants. Since then many research projects, conducted mostly in the United States, have confirmed these results.

However, the use of psychedelics is strongly discouraged for psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, since symptoms could worsen.

Escaping the therapeutic stalemate

Conventional pharmacological treatments, antidepressants and anxiolytics medication, produce highly heterogeneous responses. Dosage and side effects vary depending on the patient and their illnesses, sometimes leading to therapeutic impasses or drug dependence. In this type of situation the emergence of psychedelic therapies brings a glimmer of hope. According to recent studies, the positive effects of LSD and psilocybin are fast-acting and long-lasting. If these results were confirmed, these substances could pave the way for a profound shift in the treatment of psychiatric diseases.

Protocols like no other

Transcendent and ineffable, a psychedelic experience lasts from 4 to 12 hours and should take place within a controlled setting. In their protocols, scientists pay special attention to two things: the set and the setting. The set refers to the state of mind, expectations, psychological history and genetic baggage of patients. The setting refers to the environment and the context, the people with whom the substance is consumed. Unlike conventional treatments where a molecule is prescribed then self-administered periodically, psychedelic-assisted therapies require preparation and meticulous management before and after the substance is taken.

This unusual methodology comes from the United States. In the 1960s some in the medical profession were seeking treatment techniques to offer dignity at the end of life. At this time, the researcher Eric Kast from University of Chicago Medical School tested the efficacy of LSD in pain management. The results of his first study were surprising: in one dose, LSD proved to be a powerful painkiller. Kast, like other doctors at the time, was able to gradually improve the way in which LSD was taken based on feedback from his patients.

These studies laid the foundation for the psychedelic-assisted therapy model still used today. A single strong dose per session is needed. Patients are informed of the effect of the substance before taking it and are questioned about their expectations and their fears. The room in which the session takes place is decorated and cosy. Therapists are trained to support patients during and after the substance is taken with a suitable form of psychotherapy.

Europe invests in psilocybin

Led by the University of Groningen medical centre, the PsyPal Project received 6.5 million euros from the European Parliament in April 2024. This clinical trial will monitor over 100 patients in four different centres in the Netherlands, Portugal, Denmark and the Czech Republic. It proposes to study the effect of psilocybin in treating anxiety at the end of life related to four degenerative diseases: Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This is the very first European subsidy to finance clinical research in psychedelic therapies.

A new market?

With the surge in psychedelic medicine, pharmaceutical companies specialised in this field are flourishing. Their aim is to develop molecules approved by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration), the US equivalent of the European Medicines Agency. Some of them, including Compas Pathways, have developed derivatives of natural molecules in order to patent them. The first study on resistant depression in France will be conducted with the substance Comp360, inspired by the molecular structure of psilocybin.

Various paths towards altered states of consciousness

Psychedelics are powerful hallucinogens that act directly on the serotonergic system. Other psychotropic molecules, with very different pharmacological modes of action, are also being studied in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. For example, ketamine, for its antidepressant effects, and MDMA, the main active ingredient in ecstasy, appear to be effective in treating anxiety and post-traumatic stress. Less known substances are also being studied for therapeutic purposes, such as Ibogaine for addiction and Salvia for protecting and improving cognition.

Unlike these compounds that have only recently drawn attention in medicine, studies on psychedelics are based on a broad body of science. Research into LSD and psilocybin is evolving rapidly and more and more health professionals are becoming interested in it.

Non-pharmacological approaches such as hypnosis and meditation also show therapeutic benefits for certain mental disorders. While their mechanisms of action differ, the subjective experiences they induce can resemble those of psychedelics. This so-called “mystical” experience features four dimensions assessed by a questionnaire, the MEQ30: ineffability, transcendence of space and time, feeling of sacredness and positive mood. With elements of neuroscience, psychology and spirituality, studies on these practices encourage the exploration of human consciousness and its alteration for medical purposes.

France joins the psychedelic renaissance

The launch of clinical studies on psychedelics is difficult in France where drug policies are very strict. But lately France has been making up for lost time. In February 2024, the first French clinical trial with psychedelics, led by psychiatrist Amandine Luquiens, began in the addiction department at the CHU in Nîmes.

More recently, Lucie Berkovitch's Parisian team launched a clinical study with psilocybin on resistant depression at the Hôpital Sainte-Anne. Another should be kicking off in 2025: led by physician Luc Mallet, the Adely LSD project aims to study the effect of LSD on alcohol addiction.

Will psychedelic therapy become more accessible?

Although the therapeutic benefit of psychedelics is no longer in question, access to the therapies remains difficult. Switzerland is a pioneer in Europe, offering psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (PAP) in very specific cases of resistance to treatment. Many psychologists and psychiatrists in France lack information on the topic and training for health professionals is non-existent. If the ongoing trials turn out to be conclusive, the introduction of psychedelic therapies will require considerable human and financial resources. At a time when public hospitals are already in great difficulty, access to these treatments for a wide audience is far from guaranteed.

The future of psychedelic medicine

In 2019 the Global Commission on Drug Policy published a troubling report. According to its authors, the distinction between legal and illegal substances is based not on scientific arguments but on historic and cultural factors. Psychedelics are a textbook case of this. LSD and psilocybin are today still classified as dangerous drugs, with no therapeutic benefit. However, science tells a different story. Many scientists are calling for an urgent revision of the classification of these molecules to simplify the work already conducted.

Psychedelics seem to provoke unique experiences and bring subconscious material to the surface, and this can be worked on using suitable psychotherapies. But the method for managing this is not yet clearly defined. Psychiatrists in France are not required to be trained in different psychotherapeutic approaches, but they are the only ones able to prescribe medications. If psychedelic therapies develop in France, training for doctors will have to be adapted accordingly.

Finally, it's important to remember that there is no silver bullet for treating psychiatric disorders, but rather a combination of complementary physiological, psychological and social approaches.

Despite promising results, many questions remain unanswered concerning the mechanisms of action of psychedelics and the methodological biases of studies carried out to date.