Is integrated EU health on the way ?

During the health crisis, the powers of Europe’s public-health authorities have increased significantly. Gradually, ‘EU health’ is becoming a reality.

An investigation by Lise Barnéoud - Published on

Health was not one of the founding aims of European construction. Yet health crises caused by such diseases as H1N1 flu and Covid-19 have shown to just what extent certain health issues require joint action. Over the last few years, this has led to increasing numbers of initiatives on a continental scale. The European Union (EU) now wants to do more than just back national policies. It has its own monitoring, alert and health-action resources, approves regulations (drug quality and safety) and even carries out bulk purchasing (of vaccines for instance). And this year’s creation of an agency dedicated to health risks, Hera (Health Emergency preparedness and Response Authority), marks an additional step towards a true European health sector.

Health: a recent priority

Over the last twenty years of successive health crises, Europe has been adding to its powers in the field of healthcare.

Yet they are still limited. Health was not mentioned in the two founding European treaties of 1957. However, from 1977, a council of European ministers of health began to meet, although not regularly. The 80s saw a number of health crises – HIV, infected blood transfusions and mad cow disease – and marked a turning point. The 1986 Single Act made public health a ‘community objective’, but it took another ten years and the Maastricht Treaty for Europe to begin to support the action of member states to prevent major health risks (infectious diseases, cancer, addiction…). From 1997 and the Amsterdam Treaty, it acquired the power to implement statutory measures “to set high standards of quality and safety” for blood, organs and other substances of human origin, and then drugs and medical equipment ten years later. “The great principle is as follows,” notes Anne Bucher, former Director-General of Health at the European Commission (2018 -2020). “Europe only intervenes when an added value to cooperation between states is possible.” So especially in three areas: health crises (viruses do not stop at borders), rare diseases (no single country can deal with such a broad range of pathologies on its own) and pharmaceutical policy (through the single market), and also for some specific types of cooperation: cancer research and management, for instance.

The wake-up call of Covid-19

“The coronavirus pandemic has necessitated greater coordination within the EU, more resilient health systems and better preparation for future crises. We no longer approach cross-border threats to health in the same way,” declared Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, on 11 November 2020. Some sixty years after the Treaties of Rome and ten months after the start of the health crisis, the European executive presented a range of ambitious proposals to reinforce the healthcare role of the Union.

Post-crisis: the start of a common policy ?

After recognising its relative weakness due to a lack of prerogatives, the Union now intends to heighten its role in the field of healthcare.

The European Union has never faced such a critical health crisis. More than 84 million people infected by SARS-CoV-2 and 1.5 million deaths reported by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) by 2 December 2021 (UK and Turkey included). One after another, member states closed their borders, sometimes restricting the export of masks or even confiscating consignments meant for others but transiting through their country. In the economic domain, joint measures were rapidly implemented: financial contributions, authorisations for special public aid initiatives, and so on. But in healthcare, it was not until June 2020 that joint action was approved, especially to manage the bulk purchasing of vaccines. By the autumn, the European Commission had come up with a series of new proposals aimed at increasing the Union’s public-health powers. Among them were the improvement and standardisation of monitoring systems, the setting up of a network of approved laboratories for diagnosis and screening, and an audit of national systems to prepare for health crises. And especially, at the end of 2021, the creation of the European Health Emergency preparedness and Response Authority (HERA), responsible for preventing a new epidemic and better managing emergencies by supporting research and coordinating clinical trials. The starting point of a true European health authority? We will find out in the years to come.

Vaccine purchasing: a European success

By June 2020, rather than leaving each member state to come to a deal with vaccine producers, the Commission was organising the negotiation of advance purchases paid for with European funds. Thanks to that bulk purchasing, the EU was able to obtain low prices and ensure equitable distribution among its member states, proportionate to their population. Without that cooperation, the least rich countries could not have enjoyed such advantageous terms. In fact, outside the Union, the Balkan nations had to rely on Covax, the WHO’s system for the fair global supply of vaccines, to begin their immunisation campaigns. They started three months late and with few doses.

Pharmaceuticals: an impossible 27-partner strategy ?

Although the European Union has regulated its pharmaceutical market, it is struggling to solve its problems with pricing, supply and unsatisfied needs.

Healthcare products depend on heath policies, but also the single market, Europe’s historical raison d’être. Yet European countries all face the same difficulties: costly medical innovations (up to a million euros for a gene therapy, for instance), more frequent shortages of medicine (in France, stock outages tripled between 2018 and 2020) and increasing reliance on China and India (which produce more than 80% of our pharmaceuticals). And while there is actually a Europe-wide system of drug assessment conducted by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), decisions on pricing, reimbursement and stocks are made nationally. This leads to great discrepancies in prices and major inequalities in the availability of treatments from country to country. While in Germany, for instance, most new drugs are available immediately and reimbursed, there are delays of over a year in France, Spain and Italy. So as part of its new pharmaceutical strategy, the Commission plans to revise its legislation on medicines in 2022. The aim is to ensure that drugs are affordable, safe and available to all, relocate part of the supply chain to Europe and improve information on prices and stocks. However, it will need to convince countries such as Germany and France, which have huge domestic markets, high standards of social welfare and national pharmaceutical industries, and so reservations about standardisation and open pricing.

Relocating production ?

In 1990, Europe produced 80% of the medicines used on the continent. Today, the proportion is the opposite: 80% of its drugs come from China and India. To reduce that dependency, two options are being considered: building up strategic stocks or relocating the production of essential pharmaceuticals to Europe. With this in mind, the new HERA authority was set up at the end of 2021 and should be operational by 2022. It is responsible for assisting pharmaceutical research, development and production, including for vaccines.

Persistent hurdles

To each crisis its own surge of European initiatives. But obstacles remain to the construction of an improved European health system.

The first problem in constructing a European public-health policy is the reluctance of some states to give up their prerogatives in the area. Secondly, joint action is impeded by the diversity of healthcare organisation and funding among member states. Some, such as France, have national health services; others, including Germany and Spain, have regional systems. Like Denmark, Finland and Sweden, certain nations base all their hospital services on public establishments, while others, such as Belgium and the Netherlands, rely mainly on private organisations. Some countries allow online pharmaceutical sales while others prohibit them. All these disparities make it impossible to standardise healthcare. Indeed, the successive European treaties identifying the powers of the Union have always omitted the issue. Ultimately, despite its new post-Covid announcements and ambitions, Europe still allocates less than 1% of its resources to healthcare, while agriculture and economic competitiveness continue to absorb more than 85% of Europe’s budget. So the human, organisational, financial and political resources dedicated to Europe’s healthcare policy remain extremely limited.

Networks devoted to rare diseases

Some 30 million Europeans suffer from rare pathologies, but no single country on the continent has, on its own, the knowledge or resources to manage the 5,000 to 8,000 rare diseases currently known. So in 2017, European Reference Networks (ERNs) were set up, coordinating more than 900 highly specialised care facilities across different member states. These structures enable rapid sharing of knowledge and faster diagnosis and treatment for patients.

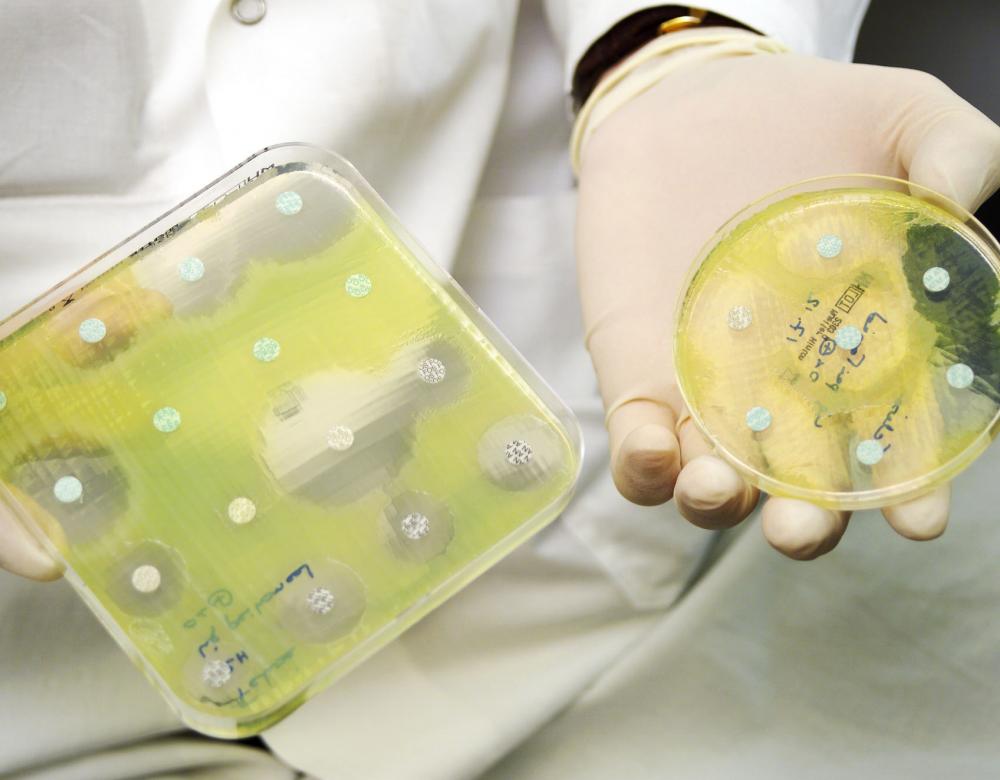

Antibiotic resistance: a joint campaign

Around 33,000 deaths and a cost of 1.5 billion euros: that is the annual price of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections in Europe! Some member states set a good example (Austria, Sweden or Germany), while others (Greece, Cyprus or France) still consume too many antibiotics. Since 2017, a European Action Plan has been implemented to ensure compliance with world objectives in terms of the proper use of antibiotics over the continent, set up a network to monitor resistant bacteria and encourage research into new compounds.

Financial backing for national policies

Indirectly, Europe contributes to national healthcare systems through the EU4Health fund, with a budget of 5 billion euros for the 2021-2027 period, and, through Horizon Europe, its funding programme for research, including medical research. More substantial cohesion and regional-development funds back local healthcare projects on a case-by-case basis. Some 7,400 initiatives enjoyed this support between 2014 and 2020 (here, a new hospital wing in Riga, Latvia). In the poorest countries of the Union, such as Romania or Greece, they are actually the main source of funding for healthcare infrastructure.