Animals: as much between the ears as we do!

Counting, tinkering, communicating, etc. From bees to dolphins and marmosets, animals excel where we least expect them to, and show unequivocally that no, humans are not the only intelligent ones!

Investigation by Magali Reinert - Published on

Multiple forms of animal intelligence

The idea that animals might be intelligent has made more than one biologist laugh. Today, the complex cognitive capacities of numerous species are no longer in doubt. For example, bees can handle abstract concepts, a discovery that dates back to 2001, when tests using various objects showed that these insects understand the ideas of similarity and difference.

As we gradually develop a better understanding of animal capacities, characteristics such as tools, culture and language, are no longer regarded as unique to humans. Research has established insect intelligence, cetaceans’ cultural practices, the linguistic skills of birds, etc.

Finally, ethology – the science concerned with animal behaviour – has evolved since the late 20th century, led most notably by primatologists who have demonstrated the importance of studying animals outside laboratories and within their natural environments. Scientists also speak more willingly about behavioural ecology. This discipline also borrows from the social sciences in order to study animal societies, and learns from other disciplines such as neuroscience and acoustics.

The capacity to adapt to changing environments, the development of responses to unprecedented situations, collective learning strategies, etc.: animal intelligence turns out to take multiple forms. Nowadays animal consciousness, in other words animals’ capacity to nurture their own experience of the world, is widely recognised by means of international declarations signed by dozens of ethologists and neurobiologists.

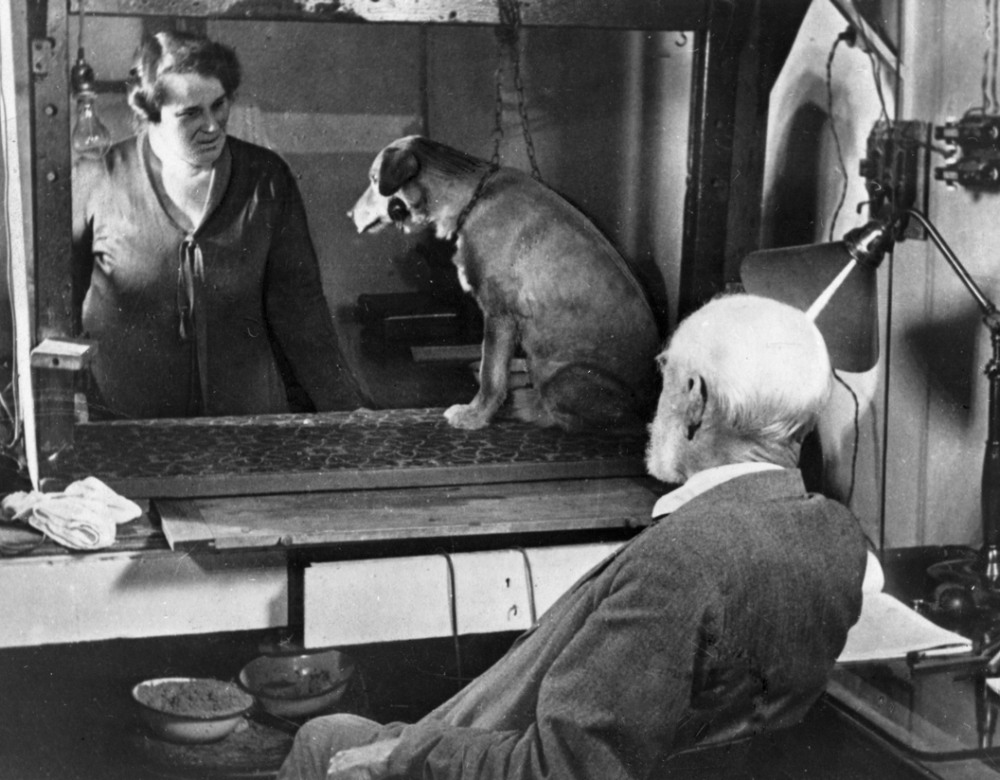

The animal machine inherited from Descartes

The Cartesian concept of the “animal machine”, an automatic being devoid of thought, has long influenced the study of animal behaviour in the West. Initiated in the mid19th century, this laboratory-based experimental approach merely tested an animal’s capacity to respond mechanically to stimuli. This was the era in which the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov conducted his famous experiment involving canine conditioning: a dog that was used to being fed after hearing the sound of a bell began to salivate as soon as it began to ring. The demonstration of this reflex reinforced the idea that despite their capacity for learning, animals were devoid of thought.

The mirror test: from humans to... fish

Until recently the mirror test, which assesses the reaction of an individual when faced with their own image, divided the animal kingdom in two: on one side were the humans who possessed self-awareness and on the other were the rest of the animals who were devoid of it. But this division has been eroded! The great apes were the first to pass the mirror test, followed by other species such as... certain fish. After having observed their reflection, cleaner wrasses into which a dye had been injected rubbed themselves in an attempt to remove the marks on their skin. The test does not work on all animals.

In the lab, in the wild... or both

Studying an animal in a laboratory or within its natural environment: the two approaches are radically different. In the laboratory, an animal is at the disposal of humans, and subject to strict protocols designed to assess its cognitive capacities. This is an advantage: placed in a situation that it would not encounter in the wild, the animal reveals its capacity to understand complex new problems. In recent example, research has highlighted bumblebees’ spectacular intelligence: by observing other bumblebees that have already been trained, they are capable of learning to pull on a string to access nectar.

But for some ethologists, animal intelligence must be studied within their natural environment. Some primatologists, women in particular – like the British-born Jane Goodall who died in October 2025 – have paved the way with the great apes. Other ethologists have studied elephants and cetaceans, revealing the wealth and complexity of their behaviour. Orca, for example, are capable of deliberately beaching themselves in order to catch sea lions, or of working together to create waves in order to destabilise a seal on pack ice. Occasionally humans fail to understand it, as in the case of groups of orcas attacking the rudders of pleasure boats, which specialists have interpreted in various ways.

Finally, certain approaches straddle both camps, for instance leaving bees free to come and go between their hives located outside, whilst using sugar droplets to attract them into the lab to take part in tests.

The mathematical talents of bees

Since they have been taken seriously, bees have proved to be good laboratory students, and particularly gifted in mathematics. They learn to choose images representing two, three or four objects, thus demonstrating that numbers have meaning for them. They can also recognise a zero. More impressive still is their ability to distinguish even numbers from odd numbers, which was demonstrated in a study conducted in 2022. The same year, another study revealed that bees mentally align figures in the same way as humans: from the smallest to the greatest and from left to right!

Each in their own world

Do intelligence tests proposed by humans allow us to understand animal intelligence? Ethology is currently preoccupied with this question which subsists due to the Umwelt (translated as “self-centred world" in English) theory put forward by the German naturalist philosopher Jacob von Uexküll (1864–1944). The idea is simple: animals experience their environments differently, depending upon their sensory systems – and this includes within the same environments. A tick, which is blind and deaf, waits in a forest for the butyric acid signal given off by a mammal, then climbs onto its prey; a bee uses polarised light to orient itself, a bat navigates through echolocation, etc.

The limits of an ethnocentric approach are obvious. Research on the octopus, for example, shows that although this cephalopod obtains creditable results in the laboratory – it is capable of unscrewing a jar –, they do not reflect the huge intelligence of this animal whose brain is distributed throughout its eight tentacles. The octopus brought surprises where they were least expected, such as the ability to sneak off and raid neighbouring aquariums! This capacity to escape from its aquarium is reminiscent of its aptitudes within its natural environment: this master of flight and camouflage is capable of imitating its environment by instantly changing the colour and texture of its skin.

Studying animal senses has thus become a promising field to explore. For example, more and more research is focusing on magneto-reception, which is the detection of the Earth’s magnetic field. Present in migrating birds, it is also found in insects, molluscs and even primates!

Bird brain

For a long time mammals appeared to be superior animals due to their neocortex, an area of the brain involved in complex cognitive capacity. But neuroscience has demonstrated that the brains of other vertebrates could also contain great densities of neurons, in particular within the pallium in birds, with quantities of neurons comparable to those in primates. Moreover, some of birds’ cognitive processes are not too different from our own: for instance, zebra finches, when asleep, experience REM sleep phases (during which dreams occur), just like mammals.

An underwater muffler

In Australia, dolphins have been observed with sponges stuck to the ends of their snouts. This accoutrement was protecting the animals’ noses whilst they foraged for fish on the seabed. Proof that these cetaceans use accessories! The use of tools, for a long time presented as the preserve of humankind, has ultimately proved to be prevalent throughout the animal kingdom. Initially observed in primates, the use of tools has been established amongst mammals, birds and even insects. Indeed, a study conducted in 2020 demonstrated that certain ants use debris as containers for transporting liquids to their anthills.

Mirror neurons

In the 1990s, the discovery of mirror neurons confirmed the existence of social emotions in animals. These neurons are activated when an individual performs an action or sees it performed by others, thus playing a role in learning through imitation and therefore in transmission, the starting point of cultural practices. These neurons are also involved in affective processes such as empathy, since they allow individuals to feel the pain experienced by others. Initially identified in humans and macaques, these mirror neurons have since been found in the brains of other mammals and birds.

Culture exists in the natural world

Collective intelligence, cooperation, learning through imitation, etc.: current research deliberately focuses on the social life of animals, revealing its abundance.

Notable differences within the social lives of several populations of a single species enable us to talk of individual “cultures”. The cultural differences between East African and West African chimpanzees are, for example, well documented: amongst the former, territorial violence between males is common, whereas amongst the latter, cooperation is generally required.

The vocal repertoires of birds also vary from one population to another – a welldocumented phenomenon amongst tits. More surprisingly, a study conducted in 2021 demonstrated differences in accent amongst naked mole-rats. Amongst these highly social rodents, such distinctions may result in tragedy, as an individual from a different colony is rapidly identified then killed by members of its own species…

Another example: recent studies have been focusing on medical practices amongst animals, and have identified a veritable plant pharmacopoeia for treating and preventing diseases. Thus injured Asian elephants eat the bark of a tree known for its antiinflammatory properties.

The education of the young plays an important role in the acquisition of these sometimes complex cultural practices. A study conducted in 2020 demonstrated that parent carrion crows in New Caledonia, known to make hooks with which to catch their prey, spend a year passing on their knowledge to their young. And – in order to perfect this knowledge – some of their young can remain with their parents for several years!

Marmosets call each other by name

In 2024, whilst recording the high-pitched chatter of marmosets, researchers noticed that these little monkeys responded to cries specifically addressed to each of them. This capacity had already been recognised within other species such as dolphins, elephants and parrots. Bioacoustics, the analysis and comparison of large quantities of sounds, thus enriches research into animal language skills. Embryonic elements of syntax have even been identified amongst Campbell’s Mona monkeys: their warning cries may be supplemented with suffixes – short cries added at the end – that specify whether the danger is coming from the ground or from the air.

Wily as a fox… or a crow!

Play is a recognised learning mechanism, and many young animals have been observed “pretending” to bite, run away, etc. This is an important stage in their exploration of their physical and social environment. Animals are also capable of deception: a crow feeding from a carcass has thus been observed playing dead whilst other crows passed close by. This was presumably to mislead them into thinking they were in danger, and encourage them to continue on their way rather than share its meal! In general, thanatosis (“playing dead”) is a ploy used by a number of species to escape predators. Or the opposite: foxes use it to get close to their prey.

A lesson for human animals

All this knowledge about animals reveals many similarities, ‘evolutionary convergences’, which provide a better understanding of the origin of emotions, intelligence and consciousness. For example, the neurochemical phenomena involved in human emotions, such as dopamine, are also expressed in mammals, birds and insects. These discoveries reposition humans within the continuum of life.

This legacy further weighs on the balance sheet of human blindness to the fate inflicted on the animal kingdom, from industrial farming to the destruction of wild species. The ethical question also permeates ethology, as this discipline contributes to strengthening animal rights by recognising their sentience. Conversely, concern for the fate of animals obliges ethologists to treat animals with greater consideration, particularly during laboratory experiments.

By putting us in our rightful place, this research challenges us to consider our ability to live with other animals. The challenge is far from being met, as illustrated, for example, by the return of the wolf to France since 1992. Is there not an alternative to weakening the protective status of this canid in Europe, as decided in December 2024?