Urban forests for livable cities?

‘Urban forests’ have been in fashion for years for a range of reasons. Yet, they are the subject of lively debate between ecologists, urban planners and planners. The fact is that trees in the city offer many benefits for the local population.

Investigative report by Magali Reinert - Published on

Why plant trees in the city?

Urban policy has been boasting about urban forests for nearly three years.

The mayor of Paris set the tone when she announced that microforests would be planted in several key sites around the capital. The images are the stuff of dreams. But what are the facts? The expression ‘urban forests’ is polysemic but there is consensus about the benefits of tree in cities. The need for nature in cities is gradually being recognised as vital for a viable urban existence. Trees are touted for providing a range of services: cooling cities suffering from global warming, improving air quality by fixing pollutants, mitigating noise, and improving stormwater infiltration. Several studies show that living in close proximity to green spaces also improves the mental and physical health of city dwellers. After being partially erased from the urban landscape in the 1950s, trees are being reinstated with urban developments for parking and traffic. In Haussmann’s concept of the city, trees had a prominent role in squares, along boulevards, and in parks where their role was to provide shade, a pleasing sight, and an alternative to ‘stale air’. But ecologists and foresters, backed by research in the field, warn that simply planting trees is not enough. The size of the green spaces, the species, the shape of plantations, and connections between them must all be considered in greening projects.

The advantages of urban wastelands

Industrial wastelands are ideal sites for restoring nature in cities. What’s more, they are often the only spaces still available. Recolonisation in wastelands by both exotic (black locust and tree of heaven) and indigenous (sycamore maple) species is more robust and spontaneous than in plantations. Some urban planners choose to preserve flora resulting from spontaneous regrowth, like in Besançon where the former industrial wasteland of the Prés-de-Vaux has been transformed into an urban park. And partially in Paris, like the old railway track encircling the capital known as the Petite Ceinture.

An ambiguous term covering groves and canopies and everything in between

The term ‘urban forest’ describes a wide range of valid solutions.

Urban microforests, the flagship development for restoring nature in cities, often springs to mind. Dense plantations of trees on small lots inspired by the ‘Miyawaki method’, they provide statistics for reporting numbers of trees planted. But many urban tree specialists believe they are less effective in meeting the challenges of greening cities than their notoriety suggests. In line with urban forestry in English-speaking countries, the definition of ‘urban forest’ must cover a more comprehensive range of solutions including woods, avenues, parks, gardens, river and canal banks, wastelands, cemeteries and isolated trees. This wider definition was endorsed by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2017. Seen from above, future cities will look more like a vast forest with asphalt clearings and concrete hills. The canopy cover index, which indicates tree cover, is how nature is measured in a city now. Urban forests are defined as complex ecosystems by foresters, covering several hectares and home to a wide range of vegetation and diverse fauna and flora. This does not include the few remaining forests spared by urban development, such as the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes on the outskirts of Paris; the only green spaces worthy of the ‘forest’ description according to some.

Miyawaki – inspired by history

Inspired by Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki (1928–2021), Miyawaki describes dense plantations of local species of three to seven plants per square metre over small areas generally under one hectare. This method, introduced in Japan in the 1970s to safeguard endemic biodiversity, has not proven to be more effective than other methods in Europe. One of the few European studies shows that 60% to 80% of the trees died within twelve years of planting. The Miyawaki method is also very expensive. Finally, climate changes are challenging the traditional preference for local species.

Canopy cover – a key indicator

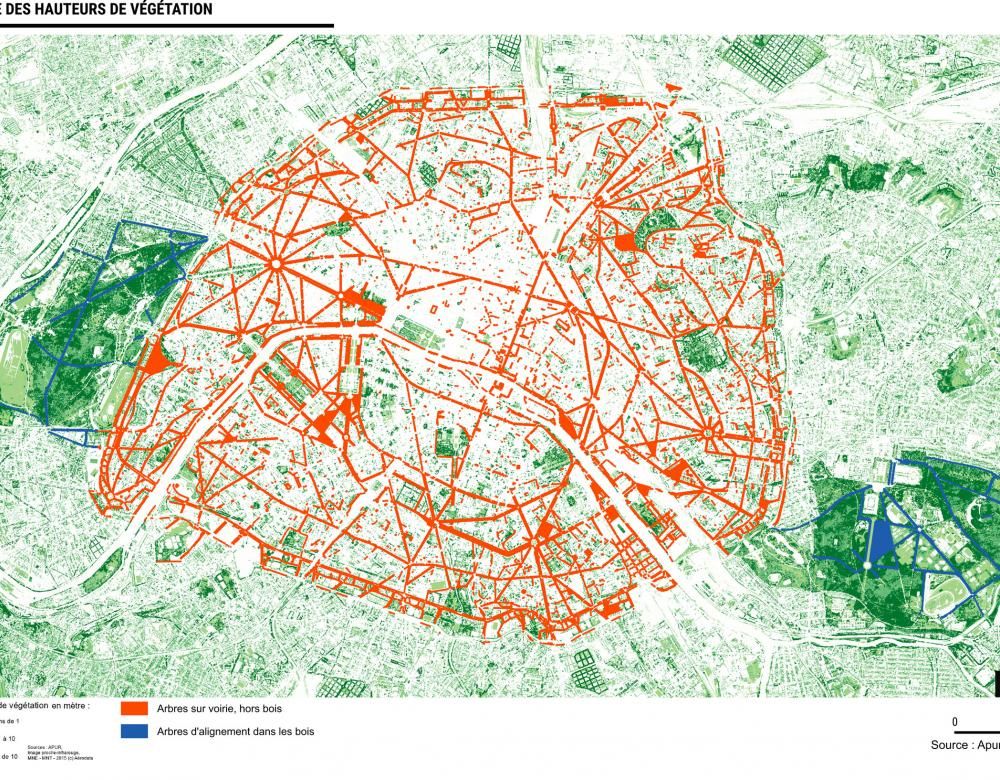

Canopy cover measures the proportion of a city’s surface covered by trees. This calculation is made using aerial and satellite images, supplemented with aerial radar which records different vegetation levels. The canopy cover index in Paris is 21%. The Bois de Vincennes and Bois de Boulogne combined represent 1,840 hectares (ha), plus 730 public parks and gardens measuring 520 ha, 600 ha of private gardens, 113 ha of cemeteries, 650 km of planted roads, 44 ha of embankments. By way of comparison, the canopy cover of Marseille is 25%, with 22% in Nantes.

Map of vegetation heights in Paris ■Under 1 m ■From 1 to 10 m ■Over 10 m ■Trees along roads, excluding avenues of trees in forests ■

Is cooling cities an impossible challenge?

Risks associated with climate change in cities, especially temperature peaks above 40 °C, are becoming critical.

Urban centres are particularly exposed due to ‘urban heat islands’ which suffer higher temperatures than the surrounding countryside, reaching up to 10 °C more during heat waves! This heat accumulation is linked to soil sealing which stores solar radiation during the day, the concentration of buildings which hinder night cooling, and the density of heat-generating human activities such as air conditioning. Trees attenuate heat. Shade reduces the heating effect of mineral surfaces. Leaves capture solar energy to sweat and stay cooler than the surrounding air. This has a slight impact on local temperatures, cooling temperatures under a tree by 7° to 8° C when temperatures are high. However, ‘natural air conditioning’ by evapotranspiration is limited during heatwaves, as trees suffering from water stress stop sweating to conserve their water content. The solution for cooling large areas is yet to be found! According to a benchmark study in 2015, it would be necessary to increase forest cover by 10% to reduce the average urban air temperature by just 1 °C! That’s hundreds of hectares.

Trees to reduce mortality during heatwaves

A study published in January 2023 in the British medical journal The Lancet studied the link between excess mortality and heatwaves. The results showed that the summer 2015 hot spells in 93 European cities caused 6,700 premature deaths. Hence, increasing tree cover to 30% of the urban area – double the current area – would lower the temperature by an average 0.4 °C, cutting deaths by a third. This calculation has even more weight given that the toll of heatwaves on human lives is aggravated by increased frequency.

Pioneering cities in Northern Europe

Northern Europe’s cities lead the way in urban forestry. Stockholm, the greenest European capital in 2010, is famous for its wooded areas covering 40% of its area.

Given the threats of global warming, urban forestry projects are spreading to the south of the continent, particularly in France and Spain. This approach, born in continental cities exposed to intense hot spells in summer in North America, points to tree cover as the best indicator of a city’s sustainability. According to this approach, 30% to 40% of a city’s surface area must be planted for it to be resilient. The current average in Europe is only 14%, with 19% in France. Lyon is the French pioneer. The city launched the first Plan Canopée in 2017 with a target of 30% tree cover by 2030 compared with an existing 27%. What sounds like a slight increase means the city needs to clear another 1,500 hectares for planting! Several cities followed suit, including Strasbourg. The Alsace capital has also undertaken to ‘demineralise’ public spaces, replacing concrete and bitumen with soil. Spectacular results have already been observed in Utrecht in the Netherlands for example, where the city closed a highway, replacing it with a canal surrounded green banks. This obliges local councils to engage with residents and the private sector as most of a city’s trees are outside the public space. For example, 60% to 80% of the three million trees in Lyon are privately owned!

Public squares and the creation of pedestrian precincts in Barcelona

Barcelona is a flagship city for ‘greening’ projects. One of the Catalan capital’s emblematic projects for urban greening is ‘supermanzanas’: blocks of buildings where car traffic is limited to 10 km/h, semi-pedestrian streets, wider pavements dotted with trees, and intersections transformed into public squares. For example, Glòries square (photo), at the junction of Barcelona’s three main routes, has been converted into a wooded park. The fast lane of the ring road has been covered in places to preserve ecological continuity.

‘Stepping stones’ in biodiversity corridors

Relations between plant and animal biodiversity must be improved to successfully ensure they are restored to the urban landscape. As a result, developing ‘green corridors’ necessary for the movement of fauna and the dispersion of wild flora has been a priority since the 2000s. Recent studies point to the role of simple sequences of small planted spaces, known as ‘stepping stones’. Like green roofs, unconnected corridors encourage pollinating insects such as bees and butterflies.

Future forest-cities

Trees face two major constraints in cities: lack of water and soil.

Urban underground spaces are like Swiss cheese, packed with networks. Some cities, such as Montpellier, are beginning to sacrifice underground parking spaces, filling them with soil. The second factor is access to water. Municipalities are developing rainwater harvesting systems and installing underground reservoirs to increase water supplies. Following the example of Strasbourg’s initiative, launched in 2010, other cities are removing artificial land surfaces to facilitate stormwater infiltration. The choice of species is also a subject for debate between experts. Giving preference to local species in artificial urban environments is not necessarily the best solution. Particularly because climate change calls for species better adapted to future conditions. As a result, INRAE, the French institute for agricultural research promotes ‘assisted migration’, planting southern species like holm oaks north of the Loire, in Paris. Ecologists prefer, however, to offer local ecological continuity with similar species for the sake of other flora and fauna, such as insects. For example, it is preferable to replace an English oak with a Mexican oak. Other researchers encourage genetic diversity within the same species to help local species adapt through natural selection of the most robust plants. Nursery workers prefer cloning plants to breeding from seeds but it is difficult to apply in the field.

Many trees at risk in the future

It is difficult to predict how trees and shrubs will cope with the increasing stress of urban environments due to more intense and frequent heatwaves and droughts. A September 2022 study published in Nature Climate Change showed that species as common as ash, oak, maple, poplar, elm, linden, chestnut and pine are already in danger. Nearly 60% of the 3,000 species studied suffer from unsuitable climate conditions. This proportion is feared to reach 70% by 2050!

Botanical gardens for inspiring species

The choice of species suited to our future cities is the subject of a lively debate but consensus prevails about the need for diversity. Monocultures are fragile as a health problem or climatic event can destroy whole plantations. Fortunately, cities have hundreds of different species in their arboretums and botanical gardens. These collections are over a century old, providing hindsight for identifying species adapted to the urban environment. France’s oldest botanical garden in Montpellier alone has 760 tree species.