Ecology: too many rats in the city?

Rats have a bad reputation when actually there are more clichés and prejudices associated with them than diseases. In fact, a healthy cohabitation with humans is possible.

Study by Lise Barnéoud - Published on

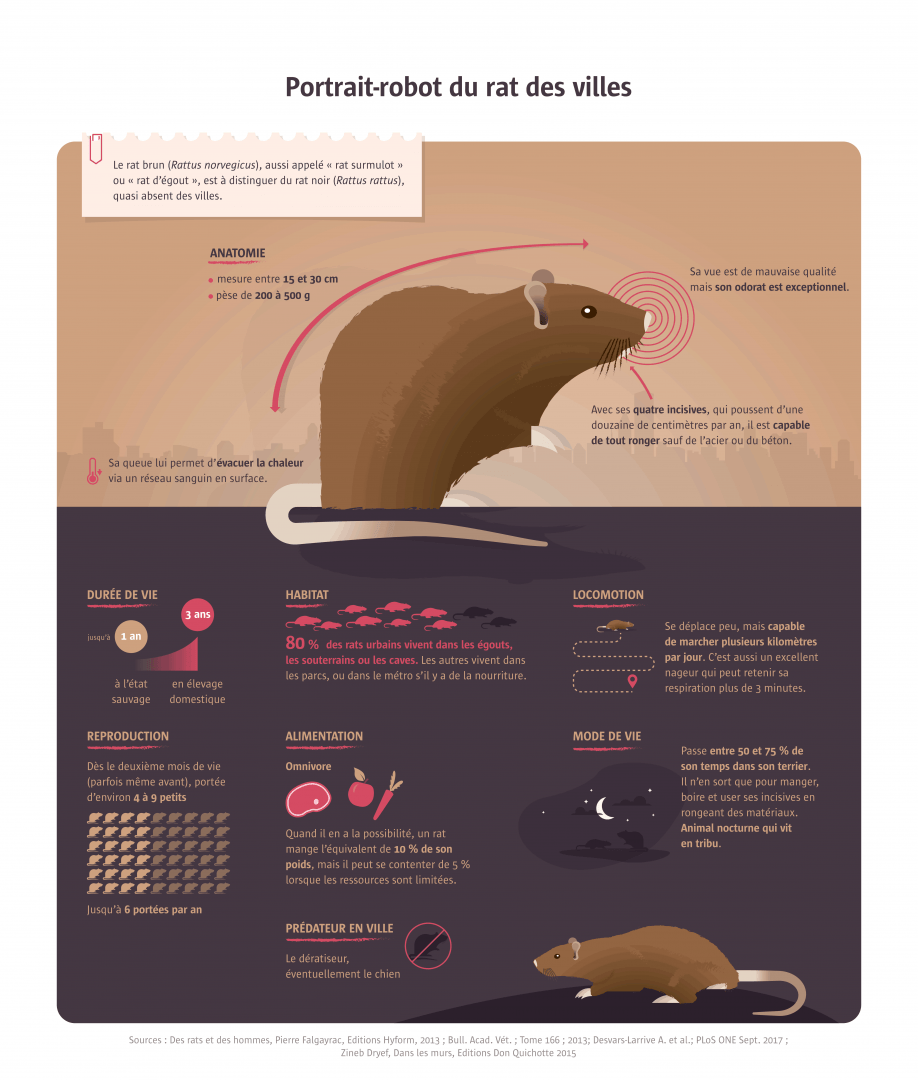

Musophobes are horrified by them, while others adopt them as pets. Some people spend their lives studying them, others eliminating them. Rats have always coexisted with humans. For a long time, this rodent, especially the black rat (rattus rattus), was considered one of the worst banes of humanity, when the plague killed millions of people in a few years. It colonized granaries, where it found lodging and cover. Today, the black rat is mostly found in the countryside. Its cousin, rattus norvegicus, also called the brown rat or the Norway rat, has replaced it in big cities. This species’ omnivorous diet with a carnivorous tendency is perfectly suited to city trash. And these rats seem to be proliferating today in Paris, New York, London, Singapore and other cities. They are everywhere: in the streets where food waste is found, in sewers, in the underground rail system, in public gardens, and sometimes even at the bottom of our toilets! Are there really more of them than before or are they simply more visible? Are there any risks in coexisting with these rodents? What methods are there to get rid of it? Are rats useful in some way? An update on these figures of darkness…

How are rats counted?

A number of indications allow researchers to estimate rat populations: the number of rats observed directly, the number of burrows, the amount of accessible food… Sometimes food is deposited in sewers to quantify what is consumed. The upshot? When there is surface food waste and old brick and rubble sewers where rats can easily nest, there can be up to 1.8 rats per inhabitant. This translates into an estimated 3 million for the city of Paris. In areas without sewers, which are cleaner on the surface, the estimate drops to less than 0.1 rat per inhabitant.

Source: Pierre Falgayrac, Des rats et des hommes (Éditions Hyform, 2013).

Increasingly visible rats

Certain changes in cities have driven rats to the surface to mingle with humans.

No doubt about it: city dwellers are seeing more and more rats in their cities. But are they really proliferating? The question is more complex than it may seem. It is impossible to count all the rats to be found in the sewers, basements, cellars, gardens, etc. Instead, the factors that determine the size of a rat population are examined – specifically, the availability of food and places to build a nest. When one of these indicators increases, there’s reason to fear a proliferation. ‘Ten years ago, following a sanitation strike in Naples, we clearly witnessed a proliferation of rats,’ comments Pierre Falgayrac, one of the few experts in the reasonable control of rat populations. In Paris, as in most other cities, there has been no significant lasting increase in available food for rats. On the other hand, food scraps left in parks or on the terrace of cafés attract rats to the surface at night. As does the trash in the frame-held plastic bags that hover a few inches above the ground. Put in place as part of the Vigipirate anti-terror measures in France, these transparent trash receptacles are a boon for rats, whose sense of smell is 1,000 times more sensitive than ours, and 10 times more discriminating than a dog’s or a cat’s. In addition, extensive excavation and demolition work drives rats out to look for other burrows. Similarly, more frequent flooding of the Seine has forced many rodents to move. In the end, there are not necessarily more rats; they may simply be more visible.

An Asian origin

Fossil distribution and genetic analyses indicate that the brown rat may be native to northern China or Mongolia. Expanding with trade along the Silk Road, they are thought to have gradually reached Central Asia. From there, they stole onto the ships of the major European powers between 1600 and 1800 and ended up colonising the whole planet, with the exception of the polar regions. In Paris, the construction of the city’s sewage system at the end of the 19th century provided the rodents with the means of sedentism: a shelter devoid of predators, opportunities for digging burrows, darkness, water and food on the sidewalks.

Sources: Puckett E. et al., Proc. R. Soc. B (Oct. 2016); Invasions biologiques et extinctions (Éditions Belin, 2006).

Are rats necessarily harmful or could they be useful?

Some see rats as pests to be eliminated. Others think they are useful and that we must learn to live with them.

For a long time, the Norway rat was considered one of the greatest banes on the planet. Together with the black rat, it is known to be responsible for 5% and 10% of agricultural losses in the world, by eating seeds, crops and stocks, but more especially by contaminating food via its urine and its excrement. Yet, it is clear that in urban areas today the main impact of the brown rat is related to the fear it triggers, a fear that could adversely affect tourism and therefore the economy. ‘Visual discomfort’ is therefore the first argument cited by the City of Paris to justify its deratting campaigns, as animal rights groups, struggling to counter the negative reputation of rats based on persistent prejudices, have not failed to point out. In the fall of 2018, Paris Animaux Zoopolis launched a campaign with posters in the Paris metro stations declaring: ‘Rats are not our enemies!’ In fact, urban rats also offer benefits. They consume the equivalent of 10% of their weight per day. Relative to the estimated rat population in Paris (about 3 million), this would represent some 100 tons of waste per day. None of this trash needs to be handled by street sweepers, trash collectors or sewer workers. According to the specialist Pierre Falgayrac, ‘by circulating through the gutter gates and digging their burrows in the silt that accumulates under these gates, rats also counteract sewer clogging.’ But rats are not indispensable for this purpose: in Monaco, for example, there are almost no rats and the sewers, recently built with concrete pipes, work very well without them.

In New York, rats don’t mix!

After studying 262 brown rats in New York City, Fordham University researchers found two genetically distinct subpopulations: the rats in the north of Manhattan and the rats in the south of Manhattan. The more commercial, business and tourist district in Midtown Manhattan, with a smaller residential population but more daily disturbances, separates the two populations and acts as a barrier of sorts, say the authors. New York, like other cities in the United States, has been fighting its rats for decades. In 2017, the mayor announced a 32-million-dollar (28 million euros) plan to derat the city.

Source: M. Combs et al., Molecular Ecology (Nov. 2018)

A boom in ‘generalist’ species

The more habitats are disturbed by humans, the more some species, such as the rat, the pigeon or the mouse, multiply.

At the expense of other species… As humans travelled and conquered new territories, they brought with them domestic animals (chickens, pigs, cows, etc.) but also a great many stowaways, such as ants, mice or rats. As a result, these species are found all over the planet, and they have gradually replaced native species. This phenomenon is called homogenization of biodiversity and it is even more striking in cities. Rats, pigeons, mice, sparrows, dandelions, ferns: the same species are found everywhere, whether you are in Europe, America or Asia. These so-called ‘generalist’ species tolerate noise, pollution and the presence of humans, unlike other more sensitive species whose populations are decreasing (skylarks, common cuckoos, etc.). A study published in December 2018 confirmed this finding again: generalist species do indeed benefit most from urbanization and they end up impoverishing local diversity. This is true in the city but also in all areas exploited by human beings. Unintentionally introduced into more than 80% of the world’s islands via human activities, the Norway rat, for example, is responsible for the extinction of many island species, especially among birds that lay their eggs on the ground. Deratting operations in some islands – for example in the islands of Molène and Ouessant – have led to a significant increase in plant and animal species.

Sources: M. Pascal et al., Invasions biologiques et extinctions (Éditions Belin, 2006) ; T. Newbold et al., PLoSBiol (Dec. 2018).

Studying Parisian rats

Samples of Parisian rat tails are currently being sent to a Lyon veterinary laboratory for genetic analysis. The aim is to evaluate their sensitivity to different rat poison molecules. Rodenticide-resistant rats have been reported since the mid-twentieth century. These resistances are linked to DNA mutations that prevent the poison from being effective. Previous studies in France and in the Netherlands estimate that about 25% of the rats are genetically resistant.

Sources: Goulois J. et al., Ecol Evol (March 2017); BG Meerburg et al., Pest Manag Sci (Nov. 2014)

Can rat populations be controlled?

Stopping the proliferation of rats requires limiting access to food and making the construction of burrows impossible.

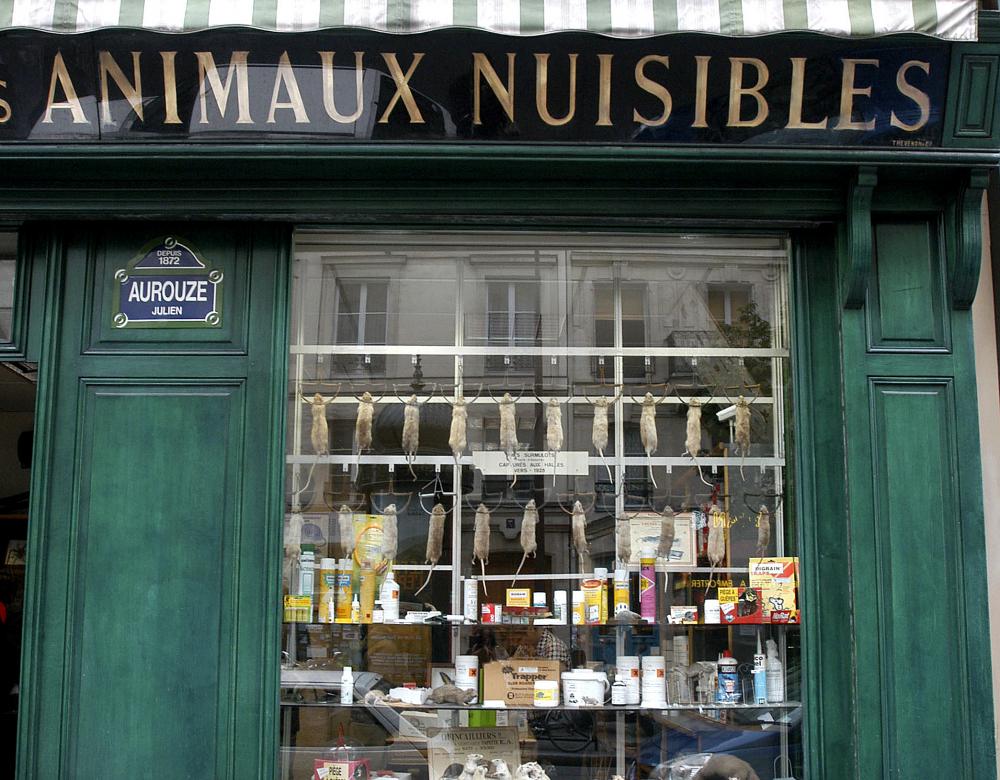

“We can live in harmony with rats, provided the city has a balanced biotope,” explains the expert Pierre Falgayrac, “which is not the case today in a number of cities and notably not in Paris”. In 2017 the City of Paris launched a campaign with a budget of 1.5 million euros to fight rat proliferation. While chemical products are the most widely used method of pest control, there are other ways to decrease rat populations in inner cities. First, reducing access to food is an effective means of control. In Paris, the frame-held plastic bags currently in use (as part of the Vigipirate antiterror plan) could be replaced by closed containers and trash collection could be rescheduled in the evening in the places most frequented by the rodents, given that rats are more active at night. Feeding other animals, especially birds, should be avoided since rats take advantage of this and eat the seeds and bread. In addition, the rats must be preventing from digging galleries or building nests, for example, by using concrete for sewers, tiling subway stations or plugging all openings with steel wool (particularly pipe penetrations). Finally, it is advisable to eliminate rats at work sites before construction, to avoid having entire colonies migrate in search of a new nest. In a different vein entirely, some crews, especially in New York, have not abandoned the use of ratter breeds, such as terriers, bulldogs, or Prague Ratters, used since the seventeenth century to catch rodents. It’s pointless, on the other hand, to use cats for the same purpose: a recent study has confirmed that they will not attack rats!

Source : M. Parsons et al., Front. Ecol. Evol., sept. 2018

Primarily chemical means of control

Since the 1950s, to prevent rats from identifying toxic substances, slow-acting toxins are used that work at a distance from the food intake. These are anticoagulants that thin the blood and cause internal bleeding. The problem is that, even though these poisons are in very small doses and are relatively harmless for humans, their persistence in the environment and in the body of rodents causes widespread contamination of the food chain (squirrel, birds, invertebrates, etc.). Thanks to regulations concerning the safety of bait stations, acute intoxications in animals are rare and no accident has been recorded in humans.

What are the health risks today?

People primarily think of rats as animals that carry diseases, like the plague. But the reality today is less alarming.

Between 1348 and 1352, the ‘Black Death’ in Europe killed between 25 and 40 million people. In the late 19th century, this disease was discovered to be caused by a bacterium transmitted by rat fleas*. In the Middle Ages, the brown rat had not yet spread to Europe: it was its cousin, the black rat, that played the role of the ‘Grim Reaper’. But today, the brown rat is also a host of the Xenopsylla cheopsis, the incriminated flea. It can potentially transmit the disease, which continues to kill people: according to WHO statistics, there were 3,248 cases of human plague between 2010 and 2015, 584 of which ended in death. On the other hand, in Europe, the bacterium responsible for the plague, Yersinia pestis, has not been detected for decades. The main health risk related to the presence of rats is something else entirely: leptospirosis, a bacterial disease that is rarely serious and which can be treated with antibiotics. But if it is not diagnosed in time, leptospirosis causes renal, pulmonary and hepatic failure, or haemorrhaging, and leads to death in 5% to 30% of cases. In metropolitan France, the incidence of leptospirosis is today close to 1 case per 100,000 inhabitants. Lastly, the brown rat is also a carrier of viruses – hantavirus, which causes haemorrhagic fevers and cardiovascular problems (extremely rare in France) and the cowpox virus, which causes for skin infections (a few dozen cases a year) – and parasites.

According to another hypothesis, this bacteria is transmitted by human fleas and lice (K. Dean et al., Pnas 115 (6) 1304-1309, 2018). Sources: F. Ayral, Thesis 2015; L. P. Angley et al., Zoonoses Public Health. (Feb. 2018); Centre National de Référence pour la leptospirose, Rapport 2018; Santé Publique France.

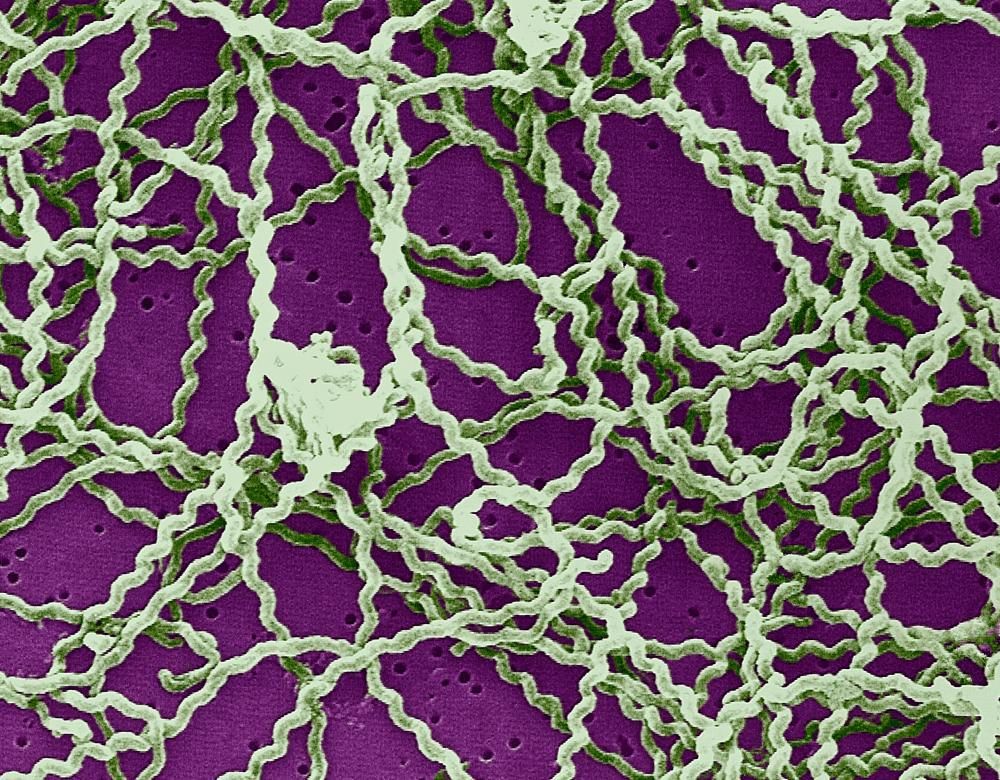

The rat, a carrier of leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a disease caused by bacteria, called Leptospira (see photo), which lodge in the kidneys of brown rats, but also of muskrats and coypus. Every time the infected (but nonetheless healthy) rodents urinate, they excrete these bacteria that can survive for weeks and even months in the water. A vaccine exists which is recommended in France for all at-risk profession (e.g. sewage workers, canal maintenance staff), but it only protects against one type of Leptospira, which causes about 30% of cases in metropolitan France. Pets (dogs, cats, guinea pigs) can also be carriers of this disease.

Small rodents, huge damage!

With their sharp incisors that grow continuously through their lives, brown rats can chew through almost anything. They can thereby cause significant material damage, including short-circuits on electrical cables, breaks in pipes, deterioration of insulation or woodwork, and even be the cause of accidents. After a collision of two trains near Pau, France that wounded 40 in 2014, the investigation uncovered the role of rats that had gnawed through the wires supplying electricity for the traffic lights.