French society’s response to the attacks

The terrorist attacks on France in 2015 and 2016 affected the whole of society. Ten years later, what traces have such horrific events left? What does sociology have to say?

Kassiopée Toscas - Published on

A strong but unequal social footprint

Still today, the symbolic weight of the events of 13 November remains heavy: they continue to be the French people’s first reference in terms of attacks, ahead of those that took place in Paris from 7 to 9 January 2015 and in New York on 11 September 2001. That is what the work carried out by the Research Centre for the Study and Observation of Living Conditions (Crédoc) shows in the context of the 13 November Programme. The memory of the Stade de France and the terraces is nonetheless eclipsed by the Bataclan, a phenomenon that researchers call “memory condensation”.

In 2016, 97% of people questioned still had “memoryflashes” of the events: they remembered the exact circumstances in which they had learnt of the attacks’ occurrence. Over the years, however, the 13 November tended to fade from memories: in May 2021, a third of the population was no longer able to recall any of the places that had been attacked. But the so-called “V13” (Friday 13th) trial, held between September 2021 and June 2022, reversed the tendency: it was high-profile and was followed by 43% of French citizens aged 15 and above, all media combined.

Sociologists have come up with another finding: the 13 November’s impact on memories was far from being uniform. High socio-professional categories, city dwellers and young people were the most affected as they were more likely to identify with the victims, who had an average age of 33. In fact, in 2016, almost 90% of 18-30 year-olds told Crédoc that they had been “personally” affected. And 64% of 18-39 year-olds mentioned the “feeling of fear” the attacks had aroused among them, as against 50 to 55% of 40 year-olds and above.

To be or not to be Charlie

On social media, the debates on the slogan “I am Charlie”, sometimes reworked as “I am not Charlie”, are an excellent example of the dual movement of cohesion and tension characteristic of the “hysteria” phase. According to sociologists, the counter-slogans combine a number of heterogeneous positions: conservative Catholic criticism of Charlie Hebdo’s left-wing spirit, French Muslims’ criticism accusing the magazine of Islamophobia, and a “leftist” criticism of the stigmatisation of a minority and the risk of security drift.

The ritual of ephemeral memorials

Attacks, school shootings (Columbine High School in the United States in 1999) and deaths of high-profile figures (Lady Di in Paris in 1997): ephemeral memorials provide popular expression of collective mourning. Anthropologists and historians agree on their recent character: in France and Europe, the phenomenon gained momentum with the 2015 attacks. Protocols were gradually developed for their archiving and removal from public roads so as to avoid conflicts. Hence, the sociologist Maëlle Bazin (Sorbonne Nouvelle) considers that “collection by the archive services has gradually become part of the post-attack mourning ritual, as the collections uploaded confer them with historical value”.

Between cohesion and social tensions

Does a terrorist attack strengthen social cohesion or increase divisions? Both at the same time, according to sociologists, along with social unrest than can last several months. On the evening of 7 January 2015, the day of the attack on Charlie Hebdo, a crowd gathered on Place de la République in Paris, and more than 4 million people demonstrated on 11 January. But the debates on the slogan “I am (not) Charlie” soon revealed dissensions: “Cohesion and social tensions are the two faces of a single process, even though they are always about ephemeral phenomena”, states Gérôme Truc, a sociologist awarded the CNRS’s bronze medal for his work on reactions to the attacks.

Such periods of unrest are conducive to heightened vigilance, as evidenced by the fourfold increase in declarations of suspicious packages in the Paris region after 13 November. Another phenomenon is unfounded panic, as in Juan-les-Pins near Nice a few weeks after the 2016 attack: caused by a noise interpreted as gunshots, there was a stampede that left several dozen people injured.

During such periods, described as “hysterical” by the American sociologist Randall Collins, isolated individuals take action due to an imitation effect (attack on a Paris police station by a man armed with a knife in January 2016) or in retaliation (vandalism of Muslim places of worship). According to the Interministerial Delegation for the Fight against Racism and Antisemitism (DILCRAH), anti-Islamic acts tripled in 2015. But this was a one-off upsurge as the number of such acts decreased significantly in 2016 before returning to their 2012 level.

After an attack, what social reaction?

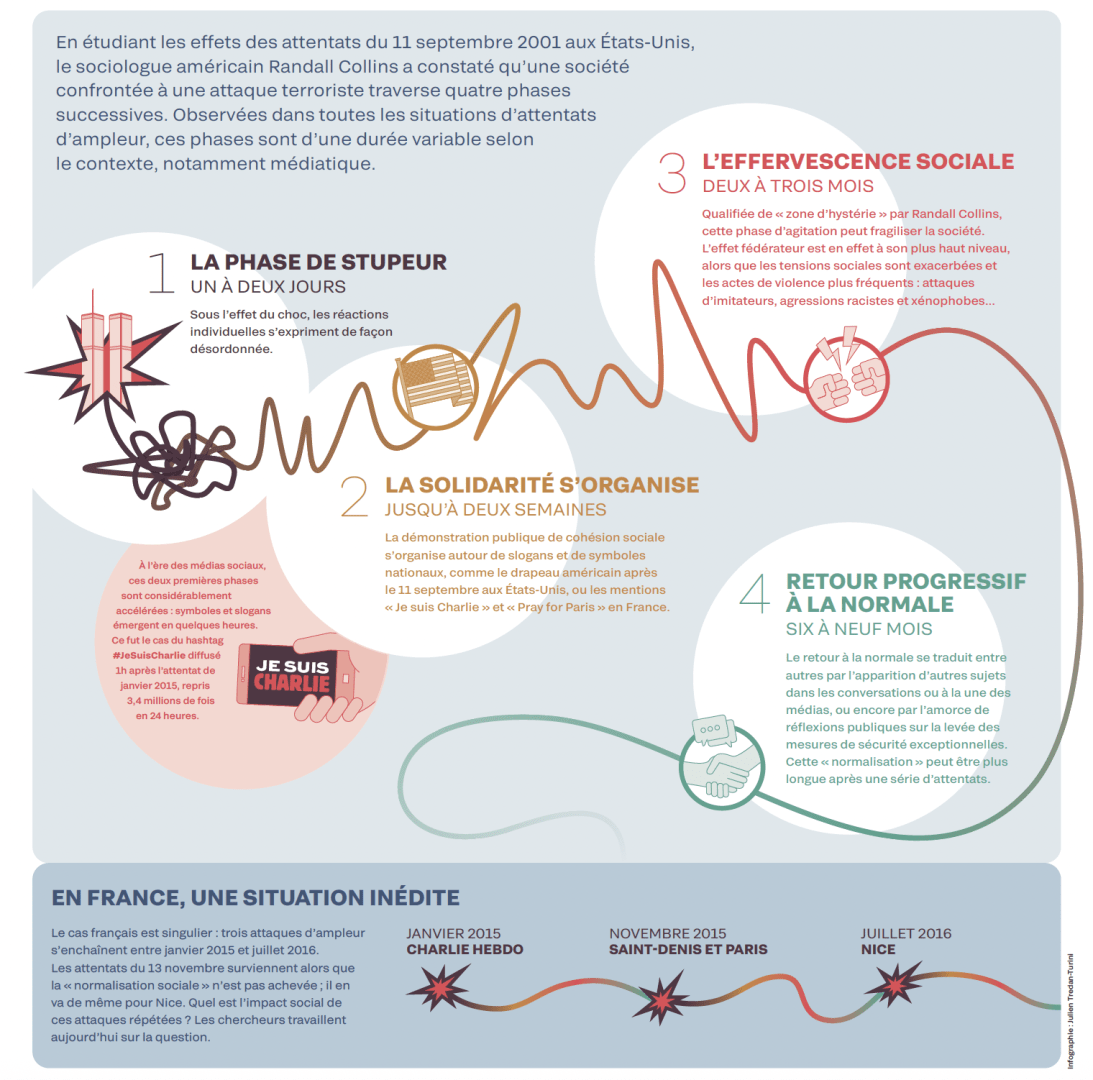

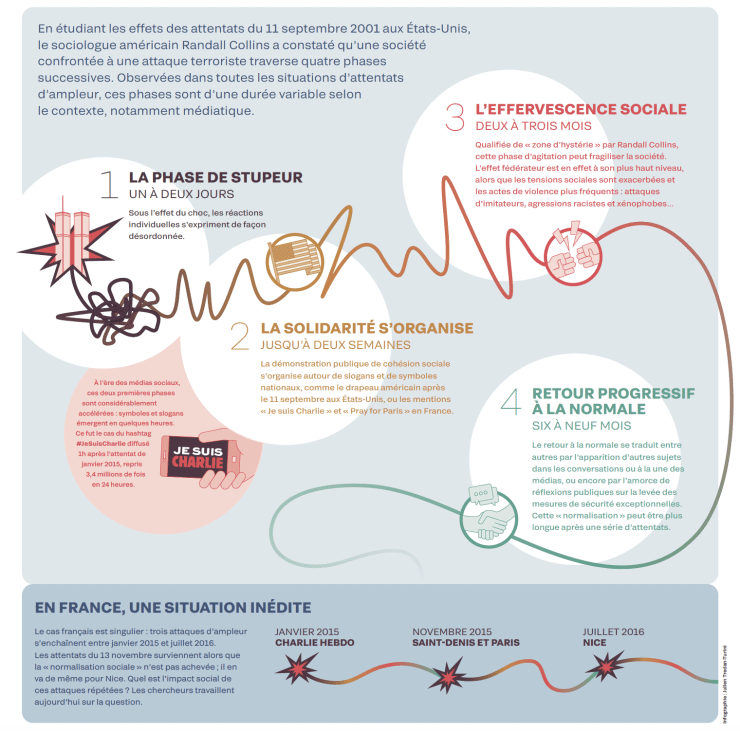

When he studied the effects of the 11 September 2001 attacks in the United States, the American sociologist Randall Collins found that a society confronted with a terrorist attack goes through four successive phases. Observed in all large-scale attack situations, these phases are of variable duration depending on context, media coverage in particular.

- The shock phase: one or two days

Under shock, individual reactions are idiosyncratic.

- Solidarity is established: one or two weeks

Public demonstration of social cohesion is organised around national slogans and symbols, such as the American flag after 11 September in the United States and the “I am Charlie” and “Pray for Paris” slogans in France.

In the era of social media, these first two phases have speeded up considerably: symbols and slogans emerge in just a few hours. Such was the case with the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie (I am Charlie), disseminated an hour after the January 2015 attack and picked up 3.4 million times in 24 hours.

- Social unrest: Two or three months

Described as a “hysteria zone” by Randall Collins, this phase of unrest can weaken society. The unifying effect is at its highest level while socials tensions are heightened and acts of violence more frequent: attacks by imitators, racist and xenophobic aggression, etc.

- Gradual return to normalcy: six to nine months

Among other things, the return to normalcy is expressed by the appearance of other subjects in conversations and media headlines, as well as by public thought being given to the raising of exceptional security measures. This “normalisation” can take longer after a series of attacks.

- In France, an unprecedented situation

The French case is unique: three large-scale attacks one after the other between January 2015 and July 2016. The 13 November attacks took place when “social normalisation” had yet to be achieved, and the same went for Nice. What impact do repeated attacks have? Researchers are working on the question today.

- January 2015: Charlie Hebdo

- November 2015: Saint-Denis and Paris

- July 2016: Nice

At school, preventive culture and secularism

After the 2015 attacks, the historian Sébastien Ledoux (University of Picardy) noted the development of “a terrorism prevention culture” in schools, with the introduction of annual “attack-intrusion alert” exercises in September 2016. Mandatory at all scholastic levels, they were disputed due to their anxiogenic effect on children. The historian also highlighted the stepping up of a “culture of secularism in schools”: increased incorporation of the theme into school curricula and teacher training, and creation of a Council of the Sages of Secularism, a training and orientation body under the Ministry of Education, in 2018.

Media excesses and the search for best practices

“An attack only exists as a social event because it is reported in the media”, Gérôme Truc points out. Hence, by their very nature, the media play a major role in the social repercussions of a terrorist attack, doing so from the moment it happens.

Yet media coverage of the January 2015 attacks resulted in a number of excesses, with dissemination of photos of the security forces’ assault on the printing house in Dammartin-en-Goële where the Kouachi brothers had taken refuge, and details on the presence of people hiding in the Hyper Cacher in Saint-Mandé. The Higher Audiovisual Council (CSA) therefore issued 15 warnings and 21 formal notices against some fifteen media outlets. After the 13 November, the CSA took the initiative by setting up a media monitoring unit. Collective thought on journalistic treatment of attacks was also engaged. “There was a whole period of deontological reflection, during which media specialists and sociologists were much in demand”, Gérôme Truc remembers.

All this led to the production of best practices guides but had little real structural impact. “No collective conclusions were drawn that might have led the public authorities to take action on the factors that structure the media field, such as market logic”, the sociologist regrets. Nor was there any adaptation of the content of journalism training courses. As a result, the reflections that had begun came up against the realities of the journalist’s work, from audience capture to the imperatives of live reporting.

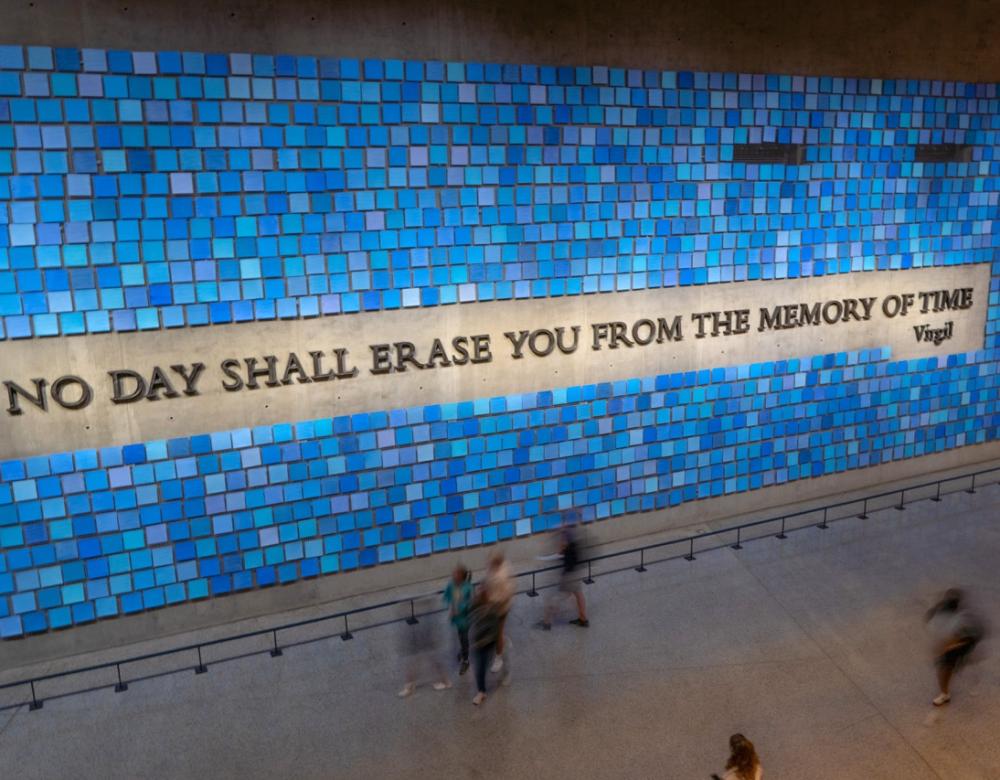

A memorial museum with a universal vocation

Terrorist attacks sometimes give rise to the creation of memorials, such as the September 11 Memorial in New York and the 22 July Memorial in Oslo (mass shooting on the island of Utøya in 2011). Such places of remembrance usually relate to a specific event. The French “Memorial Museum of Terrorism” project – currently under study – stands out by its approach. “It is unique in that it focuses on terrorism as process and mode of action, from a universal perspective”, explains the historian Henry Rousso, the project’s manager. The institution is set to open in the Paris region by the end of the decade.

On the way to more xenophobia?

After the 2015 and 2016 attacks, France might well have witnessed a surge in xenophobic opinions, as was the case in the United States after 11 September. But the picture was rather more complex. It is true that anti-Islamic and racist acts reached a peak in 2015, but sociologists stress that the fact of actually taking action must be decorrelated from major trends in opinion. In fact, “the 2015 attacks did not increase anti-Islamic opinions in the French population”, notes the sociologist Vincent Tiberj (Sciences Po Bordeaux). According to the National Advisory Commission on Human Rights’ (CNCDH) annual barometer, tolerance of Judaism, Islam and immigrants even increased between February 2015 and January 2016, without the 13 November reversing the trend.

Social science research confirms that it is not the attacks themselves that alter opinion dynamics, but the narrative that the political, social and media elites deliver about them. In contrast to the United States in 2001, when they were dominated by the narrative of the “war of civilisations”, Vincent Tiberj emphasises that “in 2015, most French public figures took care to avoid the pitfalls of conflation”.

Muslims and working-class neighbourhoods were nonetheless stigmatised by certain media discourses. “These discourses did not influence the French people’s opinion, but they left traces”, the sociologist Gérôme Truc notes. “The city of Grigny, for example, where the terrorist Amedy Coulibaly came from, was likened to a breeding ground for radical Islamism by certain media.” The city’s inhabitants even founded a collective in order to deconstruct such clichés publically.

What impact on French Muslims?

The attacks stoked a double fear among French Muslims: fear of terrorism, which they were also victims of, and fear of conflation. Certain media outlets and politicians also accused them of “keeping silent”. The sociologist Vincent Geisser (Aix Marseille University) observed “a real spiritual and civic electric shock among French Muslims”, as accusations of complicity and silence prompted them to “take action in the public space”. A decision testified to by their participation in demonstrations and posts on social media, as well as the publication of some fifteen books by well-known Muslim figures condemning terrorism and expressing their support for its victims.

A turning point for the victims?

Since 2015, French society has assigned growing importance to victims of terrorism. The setup of a one-of-a-kind judicial system for the “V13” trail bears witness to the fact, with – among other things – construction of a dedicated 500-seat courtroom and creation of a web radio enabling users to follow the trial. An unprecedented number of civil plaintiffs (over 1,800) were involved, along with “an exceptional financial, judicial, political and symbolic investment”, the sociologist Antoine Mégie (University of Rouen) notes.

On their side, the researchers Sandrine Lefranc and Sharon Weill (Sciences Po Paris) refer to a “real judicial experiment” with civil plaintiffs being able to make statements with no time limit, namely deliver “subjective account of their distress”. According to them, this was the sign of a shift “from a criminal system that examines the defendants’ responsibility to a ‘remedial’ justice system that listens to the victims”. The use of the term is debated, however, with some sociologists preferring to reserve it for the formal dialogue between victims and aggressors in the presence of a mediator.

As a matter of law, compensation conditions were extended, with the introduction of two new prejudices in 2017: “fear of imminent death” and “waiting and worrying”. Finally, in 2022, the Court of Cassation extended the notion of terrorist attack victim to “victims by ricochet ”. Hence, during the Nice attacks trial that year, a number of “unfortunate witnesses” became eligible for compensation and civil plaintiff status.

The first trials filmed for history

The 2015 and 2016 attacks trials were the first to be filmed by the National Archives pursuant to the 1985 Badinter Law, which authorises the recording of trials if they present “an interest for the constitution of historical archives of the judiciary”. But historians point out that these filmed archives are necessarily incomplete: the choice of framing created an “off-camera” in the judicial space. As a result, the victims were filmed but the defendants and incidents taking place during the hearing, including a number of heated exchanges between lawyers and defendants, are often absent from the audiovisual archives recorded during the “V13” trial.

A “Bataclan generation” in search of definition

How the attacks will be remembered is a subject that is being studied over the long term. Hence, ten years after the events, researchers are only just starting to analyse the data from the 13 November Programme’s 1000 Study interviews, with a final collection phase set for 2026. “In retrospect, we might ask ourselves if the 2015 attacks had a one-off or generational impact”, the sociologist Gérôme Truc wonders. “In other words, did they mark 2015’s thirty-somethings or rather the age group that was entering adulthood at the time?” In short, researchers are seeking to determine whether a “Bataclan generation” exists in the same way that an “Algerian War generation” existed.