Better understanding post-trauma so as better to treat it

What are the mechanisms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? What avenues are there for better treating it? Research undertaken after 2015 has enabled us to better answer these questions.

Investigation by Isabelle Bellin - Published on

A highly traumatising event

Eight to eleven months after the November 2015 attacks, 38% of civilians exposed to them suffered a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): 53% for those whose lives had been directly threatened and 25% for witnesses. Very high prevalences characteristic of reactions to intentional acts of violence, in contrast to natural disasters. That said, “the particularly high impact on witnesses surprised us”, admitted Philippe Pirard, an epidemiologist at Public Health France associated with the 13 November Programme.

Occurring after a traumatising event, PTSD results in mental distress and physical complications alike. It is detected by its symptoms: reviviscences (nightmares, intrusions of images, sensations and emotions connected with the traumatising event), avoidance of anything reminiscent of it, a permanent state of alert that prevents sleep and concentration, and emotional distress (shame, guilt, loss of self-confidence, etc.). It also causes depression, lasting personality changes, addictions, sexual and anxiety problems, dissociative disorders, even suicidal thoughts, and difficulties with social interactions.

Personal experience, such as previous traumatisms and earlier mental health problems, fosters the development of such symptoms. Hence, prevalence of PTSD is higher among women, who are more exposed to violence than men over the course of their lives. Other risk factors include isolation (felt rather than actual), precarity and poverty. But research is continuing with a view to understanding the mechanisms in play and exploring therapeutic avenues.

An invisible wound now acknowledged

Throughout the 20th century, the mental disorder that plagued combat veterans was successively termed “shell shock”, “battle fatigue” and, in 1972, “post-Vietnam syndrome” – with symptoms reminiscent of those described in the 19th century among civilian victims of physical and sexual violence. The notion of trauma first appeared in the psychiatric field in 1884 in connection with railway accidents in Europe. But it was not until 1980 that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was defined clinically, and 2013 for it to be included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

Professionals on the front line

Firefighters, soldiers, police officers, health workers and judicial personnel: several thousand professionals responded after the November 2015 attacks. Overall, they were better prepared to deal with such events than the general population. As a result, of the 663 professionals monitored by Public Health France (SPF) in the context of the 13 November Programme, 5% suffered from PTSD a year later (and still 4% four years later) and 15% from partial PTSD. The professionals most affected were those who had risked their lives by responding just after the events, before the sites had been secured.

How do you avoid or limit these symptoms? “You have to screen and treat systematically”, says Yvon Motreff, epidemiologist at SPF. “That’s what we did with the firemen, the least affected professionals in the cohort. We also demonstrated the interest of providing immediate post-attack support (debriefing accompanied with advice) for encouragement of engagement in psychological support”.

The Paris firefighters who responded on 13 November were obliged to take psychological counselling. At the Police Prefecture, however, such counselling was voluntary, which led many officers to do without it.

Finally, the professionals who were not actually on the ground may also have needed psychological support: radiologists, psychologists, lawyers and judges, as well as their supervisors. Although they are often experienced, such responders can gradually manifest symptoms of avoidance comparable to the victims’ – referred to as “indirect” (or “vicarious”) trauma.

At risk of chronic disease

Just after the attacks, victims benefited from the care provided by medico-psychological emergency units and victim support associations. However, Thierry Baubet, child psychiatrist at the Avicenne hospital, found that “a year later, half the people suffering from PTSD had not sought treatment, for fear of not being understood, shame or feelings of illegitimacy, or in order to avoid anything that might remind them of their ordeal…A good many witnesses also put off calling for help, so risking chronicisation of their disorders”. Four years after the attacks, 43% of civilians and 4% of professionals monitored in the context of a Public Health France study still suffered from PTSD.

Solutions for recovery?

It is always hard to accept: their trauma is ever present in the life of someone suffering from a PTSD. But solutions exist to ensure they no longer suffer on a daily basis. Starting with commitment to treatment, which is always possible.

For light PTSDs with no prior occurrence or comorbidity, short therapies such as cognitive and behavioural therapies and EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing) are effective. Treatment takes a good deal longer for more serious traumas such as those relating to the 2015 attacks. Medicinal treatments of proven effectiveness can reduce such disorders as depression; we also know that social and professional support of victims, management of a disability and public acknowledgement are essential to recovery.

Supporting victims, improving knowledge and disseminating it to the general public, professionals and researchers – such are the missions of the National Centre for Resources and Resilience (CN2R), created a few months after the 2015 attacks. “Its website brings together knowledge and experiences with regard to psychotrauma and resilience, including content of help to professionals”, explains Thierry Baubet, the CN2R’s Co-Scientific Manager. A clinical and therapeutic information guide for people at risk of developing a PTSD, following an attack for example, is nearing completion: enough to encourage people to request psychological treatment sooner rather than later.

Providing loved ones with support as well

Families of people suffering from PTSD need to be provided with support as the disorder’s impact affects relationships with loved ones: aggressiveness, loss of libido, addictions, etc. As time passes, symptoms may become less apparent, endured in silence, but if the disorder persists, so do related behaviours. Consequently, after the attacks in Nice in 2016, the child psychiatrist Florence Askenazy opened France’s first centre intended specifically for children: the Centre d’évaluation pédiatrique du psychotraumatisme (CE2P – Centre for Paediatric Assessment of Psychotrauma) in Nice. But the mechanisms and extent of transmission of (and resilience to) the trauma from parents to their children are still poorly understood.

Justice may comfort but does not cure

A groundbreaking study has done away with the delusion of the “reparatory trial”. “PTSD persists among 90% of victims; its symptoms were reactivated, even aggravated in 56% of them, and alleviated in 10 %”, according to the psychologist Carole Damiani, Director of the Paris Aide aux Victimes (PAV75) association. “That’s the result of the analysis of a questionnaire drawn up by PAV75 and completed by 173 civil plaintiffs at the 2015 attacks (Paris and Nice) trial, out of the 250 who attended the hearing on a regular basis (10% of all civil plaintiffs). With no psychological support, such self-disclosure is of no help.” Furthermore, the trial sometimes leads to feelings of emptiness and abandonment. Alleviation only comes months later.

A disease of forgetfulness

People suffering from PTSD relive their trauma over and over again, like a scratched vinyl disc replaying the same fragments of memories. The term “intrusive memory” is used to describe these frightening images, smells and sensations associated with the event. It was previously thought that a trauma left an indelible trace in the memory, preventing the brain from acknowledging that the danger was over. Actually though, it is also the mechanism of forgetfulness, enabling erasure of the trace (“inhibiting” it in neuroscientific terminology) that no longer functions: patients suffering from PTSD become unable to “block out” intrusive thoughts.

How is this demonstrated? “Using MRI, we analysed what was going on in the brains of 200 people subjected to a “memory suppression” test”, explains Pierre Gagnepain, researcher in neurosciences at Inserm who, in the context of the 13 November Programme’s Remember study, came up with this new avenue of research in 2020. A hundred and twenty of them had been exposed to the 2015 attacks, half of them suffering from PTSD, the other half not. Researchers compared the images of their brains with those of 80 people who had not been exposed.

Result: the memory control mechanism no longer functions among individuals suffering from intrusive memory and PTSD. “They have lost the ability to activate certain cerebral networks relating to memory inhibition”, explains Alison Mary, now a researcher at Brussels Free University, who carried out this work for her thesis. Conversely, researchers found that the mechanism functions normally among resilient people.

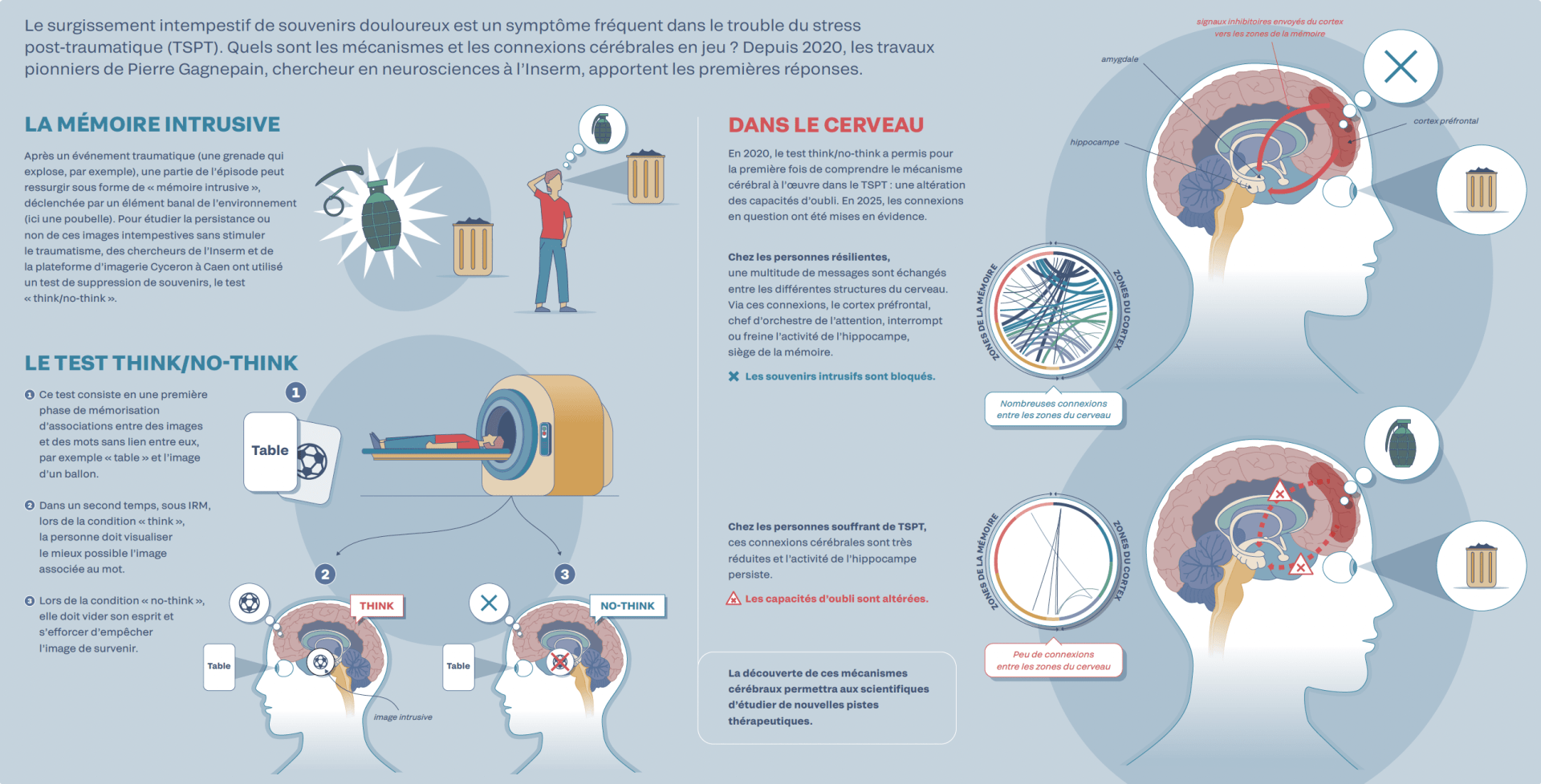

Intrusive images in the brain

The unwanted occurrence of painful memories is a frequent symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). What cerebral mechanisms and connections are involved? In 2020, the pioneering work carried out by Pierre Gagnepain, researcher in neurosciences at Inserm, provided the first answers.

Intrusive memories

After a traumatic event (a grenade that explodes, for example), some part of the episode may resurface in the form of an “intrusive memory”, triggered by some commonplace item in the surroundings (a dustbin in this case). In order to study the persistence or otherwise of such unwanted images without stimulating the trauma, researchers at Inserm and the Cyceron imaging platform in Caen used a memory suppression test: the “think/no-think” test.

The think/no-think test

- The test consists of an initial phase of memorising associations between images and words that have no connection with each other; for example, “table” and the image of a ball.

- Secondly, under MRI during the “think” condition, the subject must visualise the image associated with the word as best they can.

- During the “no-think” condition, they must empty their mind and try to prevent the image from appearing.

In the brain

In 2020, for the first time, the think/no-think test enabled understanding of the cerebral mechanism at work in PTSD: an impairment of the ability to forget. In 2025, the connections in question were demonstrated.

In resilient individuals, a multitude of messages is exchanged between the various areas of the brain. Via these connections, the prefrontal cortex, as the “bandleader” of attention, interrupts or slows down the activity of the hippocampus, seat of the memory. > Intrusive memories are blocked.

In individuals suffering from PTSD, these cerebral connections are much reduced and the hippocampus’ activity continued. > The ability to forget is impaired.

Discovery of these cerebral mechanisms will enable scientists to study new therapeutic avenues.

Other words:

- Table

- Intrusive image

- Memory areas

- Areas of the cortex

- Hippocampus

- Amygdala

- Prefrontal cortex

- Numerous connections between the areas of the brain

- Few connections between the areas of the brain

- Inhibitory signals sent from the cortex to the memory areas

The trap of avoidance

PTSD is characterised by unwanted occurrences of decontextualised images as well as by avoidance: the determination to avoid anything that might seem to encourage such images to return. A highly debilitating phenomenon in everyday life. Hence, after the 13 November, survivors stopped going to shows and cafés, or using public transport. As avoidance prevents the memory of the trauma from gradually receding, its traces remain intact and the forgetfulness mechanism remains less effective. A phenomenon studied by the neuroscientist Pierre Gagnepain, director of the 13 November Programme’s Remember study.

Seeing resilience

The hippocampus, one of the main seats of memory and learning, is very sensitive to the effects of stress. Using MRI, Pierre Gagnepain and his team observed that the hippocampus was smaller in people who had been exposed to the 2015 attacks and suffered from a chronic PTSD. “Impairment of this region contributes to the trauma’s persistence”, the researchers emphasise. Good news: the researchers also found that the atrophy stopped with remission of the PTSD and restoration of the memory inhibition mechanisms. So these processes are by no means set in stone, but capable of being developed and consolidated.

Resilience – that’s learnt!

Why do some people overcome their PTSD and others do not? Can the cerebral networks that fail to control intrusive thoughts be reactivated? The answer is yes! The researcher Pierre Gagnepain and his colleagues at Caen-Normandy University have highlighted a previously unsuspected neuronal plasticity that suggests a cure may be possible.

Using MRI, they studied structural and functional evolutions in 172 individuals’ brains: 100 who had been exposed to the 2015 attacks and who suffered or otherwise from chronic PTSD or who had overcome it, and 72 individuals who had not been exposed. “Four years after the attacks, the memory suppression test revealed the appearance of new cerebral connections among individuals recovering from a PTSD, suggesting that re-establishment of the ability to control intrusive memories speeds up resilience”, the neuroscientist explains. “Nothing is set in stone! So we’re giving thought to new therapies inspired by the test, complementary to current treatments, in order to stimulate the memory control mechanisms and re-establish failing cerebral networks.” Such treatment would avoid the patient having to relive their trauma – unlike eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) psychotherapy.

Pierre Gagnepain’s team is also working on another therapeutic target: a cerebral receptor located in the hippocampus, the seat of the memory. Studies are currently underway with a view to better understanding the influence of cerebral health and lifestyles on the mechanisms of resilience.