Race: a scientific concept?

The idea of race has a dark history, but still has a role to play in a number of scientific fields. Although its biological reality has been refuted, its controversial relevance to human science continues.

An investigation by Marine Cygler - Published on , updated on

How should we think about different human groups? The biological concept of ‘race’ – which took off when it was seized on by natural scientists in the 18th century – has been generally invalidated by genetics. It is impossible to classify individuals in hermetic groups or, worse, rank them. However, recent progress in genomics has shown nuances in this area and partially enables us to assign geographic origins to individuals. However, we should beware of drawing hasty conclusions. This new information does not support the idea of racial categories. Turning to sociologists and political scientists, they wonder about the relevance of ‘race’ from a social viewpoint, including in France – which has always preferred to focus on republican universality. But working with the historically loaded concept still remains a balancing act for all.

An attempted definition

A race can be defined as a subgroup of a species of animals with transmissible traits. For humans, that arbitrary classification, which appeared in the mid-18th century and was widely admitted throughout the 19th century, was based on immediately apparent morphological criteria as well as cultural factors. Subsequently, theories of racial classification were explicitly refuted by progress in biology. Even so, human scientists are still interested in the fact that the idea of ‘race’ remains apparent in the organisation of society.

A history of origins and classifications

The term ‘race’ is historically associated with ideas of transmission and ranking. Its study has been radically changed by scientific progress.

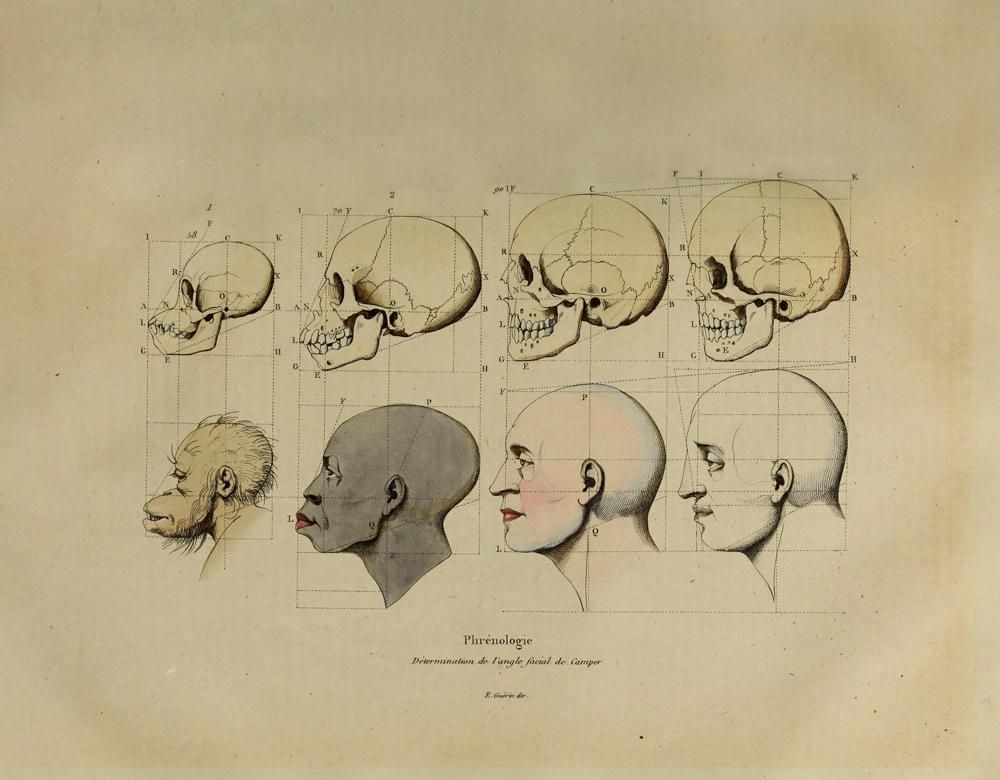

The concept of race was not an invention of scholars. In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the term was initially used to refer to a noble family, livestock or the descendants of great biblical characters. So the meaning was rather vague, but already conveyed ideas of genealogy and hereditary transmission. In the mid-18th century, the concept took off when naturalists began to classify the living world. And that went beyond just flora and fauna, because humans were also categorized according to their characteristics, which were thought to be automatically handed down from one generation to the next. Obviously skin colour, but also hair type and even certain facial features were used to classify individuals. In the 19th century, physical anthropology claimed to be able to identify the mental capacities of an individual by measuring their skeleton and especially their skull. This was the golden age of phrenology. The naturalists of the day graded different ‘races’ according to their variation from the original, perfect model: the ‘European White’. But from the 1920s, champions of genetics announced the superiority of their emerging science over morphological description. Geneticists subsequently tried to identify blood types specific to one ‘race’ or another, but unsuccessfully.

A deadly concept

Apart from aesthetic or physical traits, racist ideology also attributed psychological, mental and moral characteristics to groups of humans, some of whom were seen as superior to others. In other words, it superimposed cultural views on biological differences, justifying discrimination, oppression and verbal and physical aggression. The Nazi regime’s attempt to eradicate the Jewish people was one of the most horrific results of racist doctrine. In 1945, after the discovery of the extermination camps, UNESCO stated that the term ‘race’ should only be employed for scientific purposes, and condemned its abusive political and ideological use.

Races of humans like breeds of dog?

The term ‘breed’ is not applied to wild species today, but is used to refer to domestic animals whose traits have been selected for by humans over generations. Among dogs, physical differences between breeds are so obvious that they can be identified on sight. The same goes for their genes: a few randomly chosen markers are enough to determine whether they are poodle, greyhound or mastiff. But there is nothing so striking about human beings, whose physical and genetic differences are gradual, resulting from a common origin followed by the constant mixing of populations. So that kind of a categorization cannot be applied to people.

A (very) homogenous human genome

The gene pool of two individuals from opposite sides of the world is almost identical. That kind of similarity is exceptional in the animal kingdom.

If there were scientific proof of the biological reality of race in our genes, the genetic profile of individuals from two groups would be very different. But such variations are tiny. In fact, molecular biologists have observed that two individuals from a single group can sometimes show greater genetic differences than two others living on opposite sides of the planet. This ‘gene pool homogeneity’ is actually much greater in humans than in many other animal species. There are fewer differences between two humans chosen randomly than between two chimpanzees belonging to different groups. And for good reason: all today’s human beings are descended from small groups of Homo sapiens who appeared in Africa 300,000 years ago – a short time in evolutionary terms. Since then, long-distance migration and continuous intermixing between neighbouring populations have maintained the genetic homogeneity of the human species. At the same time, the external appearance of populations may have changed according to their habitat. That is especially the case of skin colour, which mainly varies with latitude.

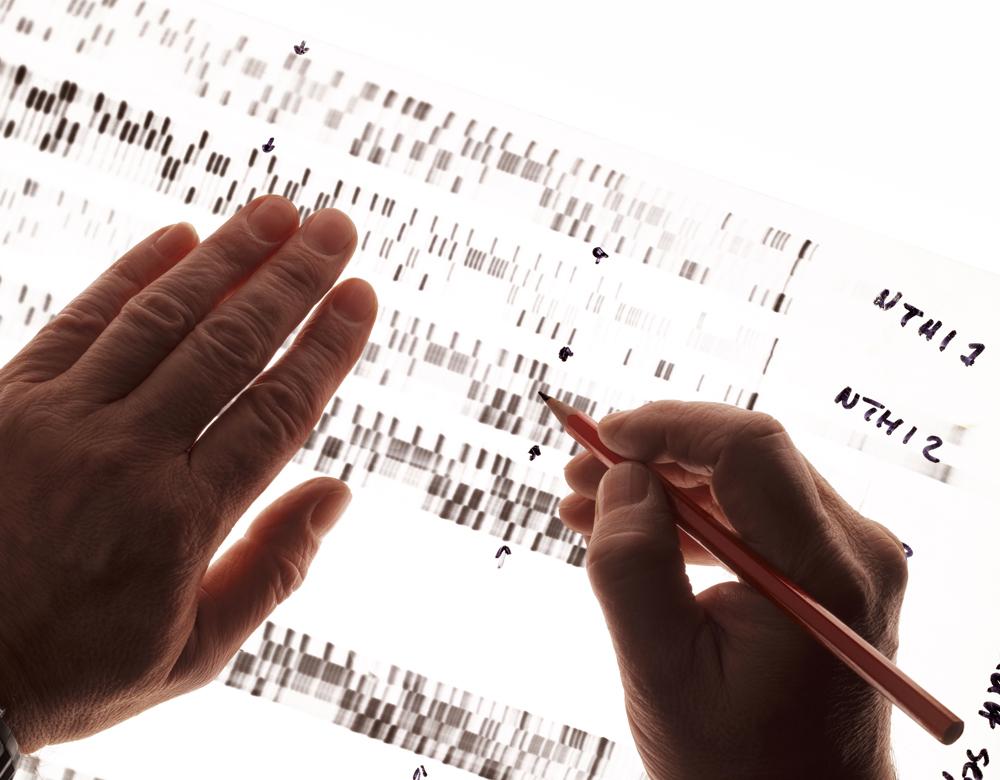

DNA superstar

Does the idea of ‘race’ have a genetic basis? In 2003, the human genome was fully sequenced for the first time. Technological progress enabled scientists to map the three billion bases – A (adenine), T (thymine), G (guanine) and C (cytosine) – that make up DNA. That sequencing once more confirmed the absurdity of the idea of ‘race’ in biology. Differences in skin colour are due to variations in just a few genes out of 20,000, i.e. a tiny share of a human’s genetic material.

The limits of genetic testing

Based on a few genetic differences between populations, private companies promise they can reveal the origin of our ancestors. Not so simple…

Even if they are few in number, certain precise points in our genome can indicate groups of ancestors or ancestral combinations. In other words, they can assign a geographic origin to an individual. This information allows population geneticists to trace the history of populations. But while the technique obviously appeals to people in search of their heritage, it mainly enriches those commercial companies that sell genealogical genetic tests. Banned in France – except by medical prescription or court order, or for research projects – such tests can still be easily ordered on the Internet. The procedure is also very simple: answer a few questions online, send a saliva sample – generally to the USA – and, of course, pay a few dozen euros. However, the fact that an individual shares their genes with populations from given regions of the globe does not mean that their ancestors came from there. That is a simplistic interpretation criticised by scientists, who are also concerned by the possibility of a resurgence of the idea of race due to searches for ‘pure’ forebears.

Could Covid-19 be racist?

In the United States, the Covid-19 epidemic has been devastating for the African-American population, which has a mortality rate four times higher than for Whites (61.6 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in June 2020, compared to 26.2 deaths). Since no genetic vulnerability has so far been identified, those excess deaths are explained by a number of factors: poverty and economic insecurity; unsanitary living conditions (cramped homes, more polluted habitats, etc.) and exposure (having to go out to work, use of public transport rather than cars); poorer access to care. A convincing illustration of a systemic racial division that affects one ‘racial’ group in particular.

A balance of power

Should the question of race be used to throw light on human relationships? While racial categories have no classifying value in biology, they can partly explain social organisation. That is the claim of certain intellectuals and researchers in France, especially in the fields of human sciences, sociology and political science. For them, ‘race’ helps us to understand relationships of power and domination. In fact, racial inequalities – e.g. access to employment and housing – continue in societies that see themselves as non-racist. So race refers to a hierarchical relationship in the same way as social class or gender.

A controversy in social sciences

In the social-science world, the debate continues. Should we use American racial categories to better describe French realities?

In the USA, five racial categories – ‘White American’, ‘Black or African American’, ‘American Indian and Alaska Native’, ‘Asian American’, ‘Native Hawaiian, and Other Pacific Islander’ – are officially used. In the US census questionnaire, ethnicity is also raised – ‘Hispanic’, for instance. There are no such classifications in France, but social-science researchers would like to introduce ethno-racial categories. They do not deny the fact that there is no biological hierarchy among humans, but suggest applying the idea of ‘race’ to develop tools to combat discrimination and help to implement specific policies for the populations involved. For a scientific approach, it would be necessary to identify groups within the population of France that could be compared in terms of both place and time. But that proposal leads to tension and fierce arguments in the French academic world, for two reasons. Firstly, the word ‘race’ remains in itself so historically loaded that some researchers do not want it to be used again. Secondly, France’s universalist culture does not recognise minorities or communities within the Republic. Ranging from denial of the existence of minority groups to a desire for their complete institutionalisation, there are many shades of opinion among intellectuals. The compromise position is an ‘intersectional’ approach, which, to analyse society, adds questions of gender and race to the traditional issue of social class.

Ethnic data: an exception for researchers

France’s ‘information technology and freedom’ law of 1978 prohibits the ‘collection or processing of personal information that directly or indirectly reveals racial or ethnic origins…’ However, there is an exception for research, especially major surveys which – when examining discrimination, for instance – may justifiably ask about the skin colour or nationality of parents. This type of research – which only began at the start of the 2000s – is closely supervised by the National Council of Statistical Information (CNIS) and the National Information Technology and Freedom Commission (CNIL). The use of statistics about minorities is also a subject of debate in the world of French research.