Sargassum: a large-scale invasion

Sargassum, once rare, is now invading the shores of the Caribbean. Foul-smelling and toxic, it brings with it health, environmental and economic challenges.

Report by Marie Brière de la Hosseraye - Published on

Sargassum, the new scourge of the Caribbean

It’s an invasion that’s poisoning the Caribbean: masses of brown seaweed, known as Sargassum, wash up on the coast in successive waves. It’s a phenomenon that’s difficult to control and is reminiscent of the green algae problem in Brittany (France), although the causes and consequences are different. Although these plants have existed for 30 million years, they have only become a problem in the last ten years or so, when they began reaching the coastline. Their proliferation has spread to the heart of the Atlantic Ocean. This is where the great belt of Sargassum is found, stretching over 8,000 kilometres, or eight times the length of France. In 2018, a record year, this Sargassum belt was made up of 20 million tonnes of algae, a mass equivalent to that of 200 aircraft carriers! It was a dark year for the West Indies and the coasts of Florida and Mexico, whose turquoise-blue lagoons turned brown. The massive strandings that year led to the closure of several ports and schools in the West Indies. When the algae decays it releases toxic gases whose smell is a nuisance to the local population and scares off holidaymakers, as well as exposing the soil to heavy metals that are toxic to humans and the ecosystem. Between December 2022 and January 2023, the amount of seaweed off the Caribbean coastline doubled, an unprecedented rate that heralded record strandings. In the end, the amount was less in 2023 than in 2018, but the recurrence of this phenomenon leaves the regions concerned no choice but to look for ways to adapt.

Brown algae present for half the year

Ten years ago, Sargassum reached the coast for two months of the year at most. Today, it is present for most of the year, sometimes from February to October. The local authorities concerned do their utmost to remove it as quickly as possible, before it accumulates and putrefies near people’s homes and businesses. In 2022, France introduced a €36 million "Sargasso plan", including €9 million for research and €27 million for monitoring and combating strandings, by developing dams, removal and storage methods. In 2018, a record year, clean-up alone cost the Caribbean almost 120 million dollars.

The Sargassum journey

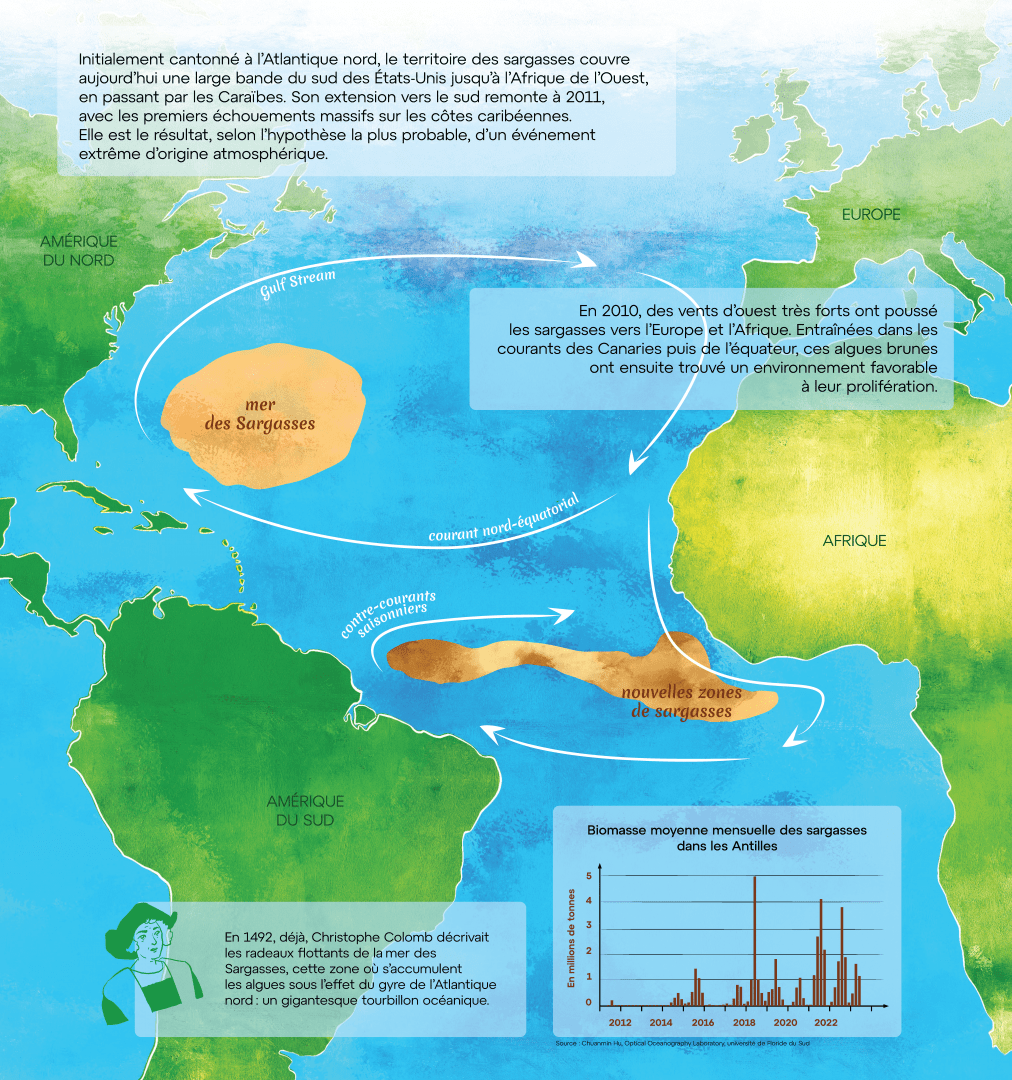

Initially confined to the North Atlantic, Sargassum now covers a wide band from the southern United States to West Africa, via the Caribbean. Its spread southwards dates back to 2011, with the first mass strandings on the Caribbean coast. The most likely hypothesis is that it is the result of an extreme atmospheric event.

In 2010, very strong westerly winds pushed the Sargassum towards Europe and Africa. Carried by the currents off the Canaries and then the equator, the brown algae then found an environment that favoured its proliferation.

As far back as 1492, Christopher Columbus described the floating rafts of the Sargasso Sea, the area where seaweed accumulates under the effect of the North Atlantic Gyre: a gigantic oceanic whirlpool.

Graph: Average monthly biomass of Sargassum in the French West Indies.

A threat to human health

For local residents living close to beaches, washed-up Sargassum poses a health threat. The fumes from its decomposition can trigger headaches, nausea and vomiting. The main culprits are two neurotoxic gases: ammonia and hydrogen sulphide (H2S), easily recognisable by its rotten egg smell. It is this gas that has been blamed for the deaths and illnesses connected to green algae in Brittany, France. Even in small amounts, it can irritate the eyes and lungs, especially in vulnerable people, children and the elderly.

When the duration of exposure or the concentration of gas in the air increases, intoxication becomes more severe and can cause neurological or heart problems. At sea, the gas is generally diluted in the air. But when the strandings become large-scale and the concentration of H2S exceeds the threshold of 5 ppm (parts per million), the public authorities strongly advise people not to go to the areas at risk and to stay downwind of the emissions.

However, the consequences of chronic exposure to low doses, such as that suffered by residents living close to beaches where seaweed accumulates, are unknown. No study has yet been devoted to assessing the long-term impact of annual exposure. But the subject deserves to be studied. In 2022, a study by the Martinique University Hospital showed that pregnant women living less than 2 km from areas where Sargassum washes ashore were more likely to develop pre-eclampsia earlier in their pregnancies than women with less exposure. This condition, linked to high blood pressure, increases the risk of premature birth.

The anatomy of pelagic seaweed

Sargassum is a type of brown seaweed known as pelagic: it lives in the open sea, and does not need to be anchored to the seabed to start its life cycle. Small pockets of gas, known as pneumatocysts, allow the algae to float to the surface. When these pockets break loose, the algae sinks. It reproduces by vegetative fragmentation: a cut piece regenerates a new individual. This makes crushing Sargassum in the open sea an infeasible way of getting rid of it. Although there are hundreds of types of Sargassum, only three have been identified in the West Indies. These three giant species therefore cover thousands of km2. But how they grow is still poorly understood.

Seaweed laden with heavy metals

Like all algae, Sargassum captures and accumulates the chemical compounds it comes into contact with. It is loaded with arsenic, a toxic substance, and cadmium, a carcinogenic and mutagenic substance. In the West Indies, some batches are even contaminated with chlordecone, an insecticide that was previously used on banana plantations and is now present in the region’s waters.

Once washed ashore, the Sargassum is removed to storage areas, usually behind the beaches, where it rapidly decomposes. This green waste not only releases its odour, but also heavy metals.

In 2020, a study funded by Ademe (the French Environment and Energy Management Agency) and carried out by the BRGM (French Geological and Mining Research Bureau) showed that the black “juices” flowing from decomposed Sargassum could contain concentrations of arsenic well in excess of regulatory thresholds. Most of the sites surveyed exceeded these thresholds, whether in groundwater or surface water. In addition, the salt in the algae also impacts the environment around the storage sites. All these pollutants are then discharged into groundwater.

And that’s not all. At present, Sargassum is sometimes used as fertiliser or compost. The authorities now advise farmers against using it as a natural fertiliser, as these pollutants easily seep into plants through the roots. That said, the regulatory tools are still lacking to manage deposits of Sargassum and the associated pollution risks.

At sea, on land, from a shelter to an obstacle

In the open sea, the seaweed forms drifting islands, hence its nickname: “floating rainforest”. These vast rafts serve as breeding grounds for hundreds of species of fish. Even European eels migrate to them to reproduce. For the young turtles that hide there, the rafts provide both shelter and a mobile feeding ground. On the other hand, the density of shoals along the coast can suffocate seagrass beds by cutting off sunlight. The 2018 waves of brown algae are thought to have contributed to coral bleaching. On beaches, the clumps also obstruct sea turtles “egg-laying sites and hinder the hatchlings” journey to the ocean.

The unexplained causes of proliferation

Among the many questions raised by the proliferation of these invasive plants, there is one that remains a mystery. Why has Sargassum become so abundant in the tropical Atlantic?

For a long time, nutrients in the Amazon and Congo rivers were thought to be the cause. Every day, their waters are contaminated by fertilisers used in intensive agriculture and the local soils, eroded by deforestation, are no longer able to absorb the excess chemical inputs. This pollution generates an influx of phosphate and nitrate into river water, which then flows into the sea, where it stimulates the growth of marine plants. In fact, the amount of nitrogen in algae samples increased by 35% between 1983 and 2019, according to a 2021 American study published in Nature Communications.

However, a French public study by the Foresea project (Funding Ocean Renewable Energy through Strategic European Action) seems to contradict this hypothesis, as only 10% of the Sargassum biomass is found in the path of river water. In addition, no major spikes in phosphorus from the Amazon were observed during 2015 and 2018, the record years for strandings. While the pollution of these rivers is very real, their role in the proliferation of brown algae would appear to be minor. New studies alone will provide a better understanding of this phenomenon.

In any case, algae grows best when surface water temperatures fluctuate between 28 °C and 31 °C. With climate change warming the oceans, the reproduction of Sargassum could worsen still.

Rallying on tourist beaches

Sargassum is a very heavy burden for the whole of the Caribbean, whose idyllic beaches and crystal-clear waters are usually very popular with tourists. In the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, tourism accounts for 80% of the economic activity. Hoteliers hire teams to clear the beaches, but when there’s a massive influx of algae, the clearing efforts are not enough. In the Dominican Republic, in the canton of Boca Chica, which has been hard hit by strandings, tourism fell by 85% between May and June 2023.

Floating booms to curb strandings

To prevent the brown seaweed from washing ashore, the commune of Le François in Martinique has installed 3 kilometres of nets along its coastline. A boat, the Sargator, is responsible for extracting the seaweed from the water, drying it and then releasing it further offshore, where it sinks. This is an experimental solution whose effects on the seabed ecosystem have not yet been studied. These floating booms with wide nets for collecting at sea can be found all over the Caribbean. Another system exists: a rigid, less costly boom that diverts the flow of seaweed to a distant shore, for collection away from busy beaches.

Living with Sargassum

For researchers and local residents alike, the conclusion is clear: the Caribbean must learn to live with Sargassum, because it is here to stay. There are two priorities: to speed up removal while limiting the risks to the environment and to humans; and to make the most of the biomass that is available in such large quantities.

For the time being, some municipalities are still lacking the money to collect all the seaweed, or are resorting to diggers that erode the beaches by removing sand along with the Sargassum. To date, no ideal collection solution has been found. However, processing the Sargassum would enable this enormous amount of biomass to be put to good use. A number of avenues are currently being explored. In Jamaica, they are trying to turn Sargassum into coal; in the West Indies, they are experimenting with fertilisers; in Brittany, bio-plastic initiatives are on the increase. In Guadeloupe, scientists are looking to transform seaweed into activated carbon to sequester pollutants such as chlordecone in the soil.

However, there is one major constraint: these marine plants are seasonal. In addition, their strandings cannot be predicted with sufficient accuracy to constitute a viable raw material in the hands of entrepreneurs. For this to happen, fresh seaweed would have to be available in regular quantities, and an efficient collection method would have to be available close to the coast.

Once promising projects have been identified, their large-scale development needs to be encouraged. The road to recovery remains full of pitfalls.

The construction industry rises to the challenge

In Mexico, Sargassum is used to make bricks; the Sargablock company produces almost 1,000 a day. It was founded by Omar Sanchez, previously a member of the cleaning teams responsible for collecting the seaweed every day in front of the hotels. The biomaterial he has developed is made up of 40% Sargassum, with the rest coming from other organic matter. The first house built in this way used more than 2,150 blocks, or 20 tonnes of Sargassum. And it is proving to be resistant to the region’s bad weather and hurricanes. In Brittany, France, the company Terre d’Algues is also developing bricks for the construction industry.

Buoys and satellites to the rescue

How can we better predict strandings in the future? This information is essential for anticipating influxes and therefore collection needs. But it’s not easy to model and predict the quantities of Sargassum several months in advance: the complexity of currents and the growth and mortality of the algae all need to be taken into account. Even collecting exhaustive satellite images in a region with a lot of cloud cover is a technical challenge! The French SargAlert project is therefore seeking to develop camera-equipped buoys capable of detecting unnoticed rafts of Sargassum and assessing their depth underwater.