Attacks: research goes into action

In the wake of the 13 November 2015 attacks, French research went into action in unprecedented fashion. Ten years later, what lessons can be learnt from it?

Investigation by Mélissande Bry - Published on

Immediate scientific mobilisation

Shock. Again. Ten months after the attack on Charlie Hebdo in January 2015, Paris and its inner suburbs suffered eight terrorist attacks. There were shootings and suicide bombings at the Stade de France in Saint-Denis, in the Bataclan’s auditorium and in several bars and restaurants in the 10th and 11th arrondissements. With 130 dead and 413 wounded, 99 of them critically, the attacks that took place in the evening of 13 November 2015 were the third most deadly in Europe to date, after those in Madrid in 2004 and Crocus City Hall in Moscow in 2024.

Just five days after the attacks, the CNRS launched an “Attacks-Research” call for projects, a determined move seeking to mobilise research efforts. For Alain Fuchs, President of the CNRS at the time, “science can provide, if not solutions, at least new avenues for analysis and action”. Out of the 320 submissions sent in from all over France, 66 projects were selected and provided with a total of 800,000 euros. Use of this budget enabled a number of laboratories to “step to one side” and explore new aspects of work already underway; others chose to devote themselves fully to the subject through their respective disciplinary fields.

This call to action led to the adoption of a wide range of scientific approaches at the service of society, in a fashion unprecedented in scale and rapidity. The very ambitious 13 November programme, inaugurated in January 2016, enters its fourth and final phase in 2026. The data collected during the study will continue to be analysed over the coming years.

Transdisciplinarity at the heart of the projects

Historically, the humanities and social sciences were the most invested in the question of the attacks, with 83% of the projects submitted to the CNRS in 2016 in the context of the “Attacks-Research” call. But one in every six projects was developed in collaboration with other disciplines, including information science, mathematics and biology. This approach led to bridges being built between sciences that had never or hardly ever dialogued before, such as sociology and the neurosciences. And to meeting a range of challenges, including interpretation of data from transdisciplinary protocols, as well as different analysis methodologies and the choice of journal in which to publish results.

Unprecedented collaborations with people on the ground

In order to conduct their research effectively, scientists forged collaborations with institutions that operated very differently from academic structures. Hence, the researcher Pascal Marchand, a specialist in communication, worked with RAID, a national police unit, with a view to improving crisis negotiation by using discourse analysis tools. Another example, the POLAR project, completed in 2016 thanks to CNRS funding, had archaeologists and police officers collaborating to investigate the trafficking of antiquities in order to finance terrorism. The goal was to combine areas of expertise so as to take stock of the problem and come up with effective protocols to combat it.

The extraordinary 13 November Programme

Overseen by the historian Denis Peschanski and the neuropsychologist Francis Eustache, the 13 November Programme (Inserm / Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University / CNRS) is the most ambitious project resulting from the CNRS’s call. Its goal is to understand how individual and collective memories of the same traumatic event are constructed and nourish one another. Inspired by the American psychologist William Hirst’s work on the 11 September 2001 attacks and transdisciplinary studies on memories of the Second World War, the programme’s innovative design is spread over more than 10 years and structured around two main protocols.

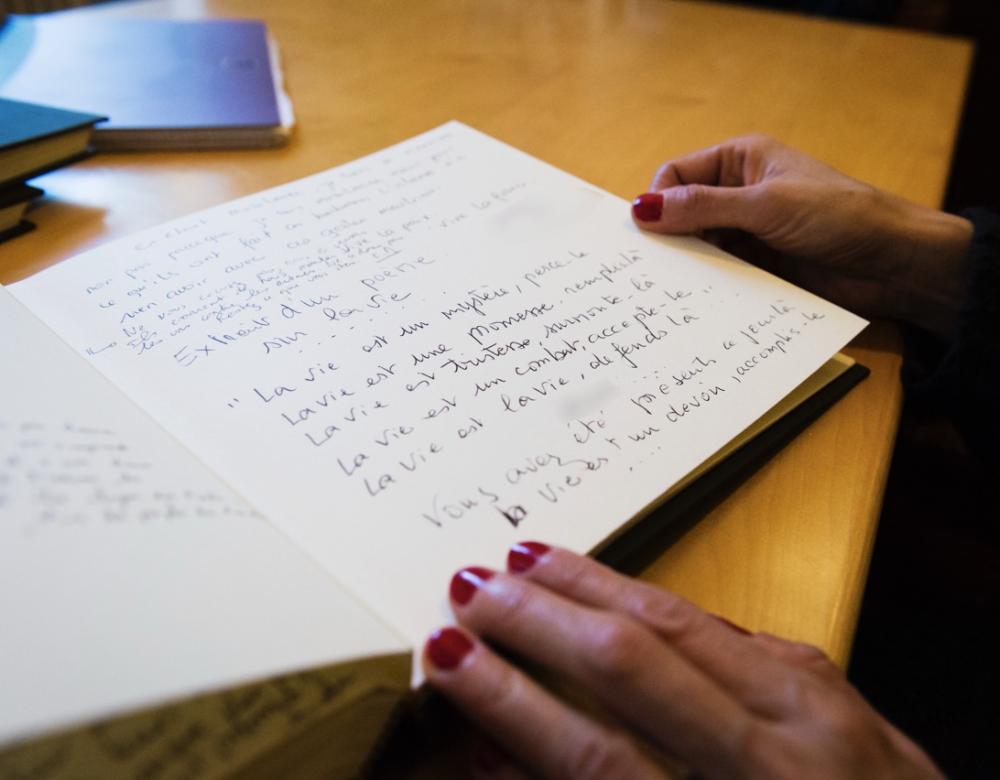

“The 1000 Study” consists of the collection, preservation and analysis of the testimonies of a thousand volunteers divided up into four circles depending on how close they were to the attacks. Interviews are conducted four times (2016, 2018, 2021 and 2026), as far as possible with the same people. Carried out in collaboration with the National Audiovisual Institute (INA) and the Ministry of Defence’s Communication and Audiovisual Production Unit (ECPAD), interviews are filmed, transcribed and carefully preserved as historical documents.

Directed by the neuroscientist Pierre Gagnepain, the second half is the biomedical study “Remember”. Based on medical imaging, it identifies the consequences of the attacks on the brains of 180 volunteers participating in the 1000 Study. It has already led to better understanding of the mechanisms of traumatism, while analyses of the thousand interviews began recently and will continue for several more years.

* This programme received government funding managed by the French National Research Agency under France 2030 (ANR-10-EQPX-0021).

From emotion to data

Designed with a dual concern for scientific rigour and ethical awareness, the 1000 Study questionnaire is divided into two parts: a semi-structured interview in which the interviewee can speak quite freely, and a structured questionnaire on emotional memory. Several long years of transcription work follow. Scientists make use of the resulting data, some of them with the help of textometry software, to carry out quantitative and qualitative analyses. Combining sociology, linguistics, psychology, history and computer science, their work has shown, for example, that there are linguistic markers for post-traumatic stress disorder, and still has much to reveal.

Taking the population’s pulse

In the context of the 13 November Programme, participants are recruited on a voluntary basis: they do not constitute a group characterising French society as a whole. In order to gain an understanding of the collective memory, the 13 November Programme has partnered with Crédoc’s “Living Conditions and Aspirations” survey, which has been questioning representative samples of the French population for more than 40 years. Several questions on the attacks have been included in the successive waves of surveys since June 2016. According to the July 2023 survey, 13/11 is still the most significant attack in France: the vivid memory of the Bataclan eclipses everywhere else.

Working on sensitive subjects

When it comes to “sensitive” subjects, research on the attacks sometimes runs up against a few obstacles. The example of the “Sustainable Cathedrals” project led by the mechanical engineers Paolo Vannucci and Ioannis Stefanou is a a textbook case. A winner of the CNRS’s call, it aimed to study ways of protecting a gothic cathedral’s structural integrity against potential explosions, taking Notre-Dame de Paris as an example.

In 2016, the researchers presented the results of their work to the CNRS and several ministries: a report warning of major fire risks to the monument and outlining preventive measures. But their report is nowhere to be found today. Its authors and the CNRS maintain that it was classified as “For Your Eyes Only” following the fire at Notre-Dame Cathedral on 15 April 2019. Details of the building’s structure and its weak points in the event of an attack are considered “sensitive” as they would be risky if they fell into the wrong hands.

Other researchers focus on online data with the aim of detecting malicious messages, developing sophisticated cybersecurity tools or identifying terrorist networks – one example being the Request project, which brings together CNRS laboratories and private enterprises. Information is sometimes hard to access, forcing researchers to follow strict data access procedures. In this regard, the CNRS’s Humanities & Social Sciences Operational Ethics Committee, created in June 2024, gives thought to anonymisation and protection of data used in research.

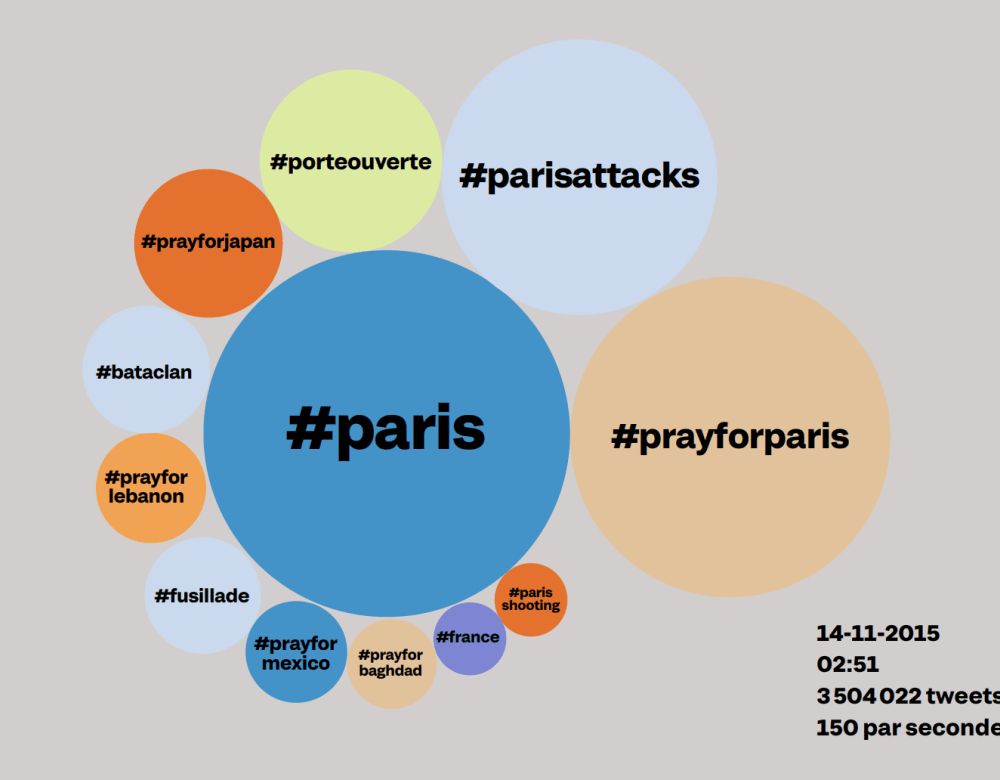

Archiving the web, a question of speed

Since the attack on Charlie Hebdo in January 2015, the National Library of France (BnF) and the National Audiovisual Institute (INA), which are responsible for legal deposits of web-based materials, have organised emergency collections. These digital corpuses, and in particular the conditions under which they are created, are at the heart of the ASAP project (Archives Sauvegarde Attentats Paris / Backup Archives of the Paris Attacks) directed by the historian Valérie Schafer. The archivist have to find answers to a number of questions: What should they preserve among the mass of data transmitted? How do they follow online expressions? What hashtags and emojis should they follow and why? This documentation work will enable development of tools facilitating analysis of these extensive corpuses from the web.

Experimental sciences put to use

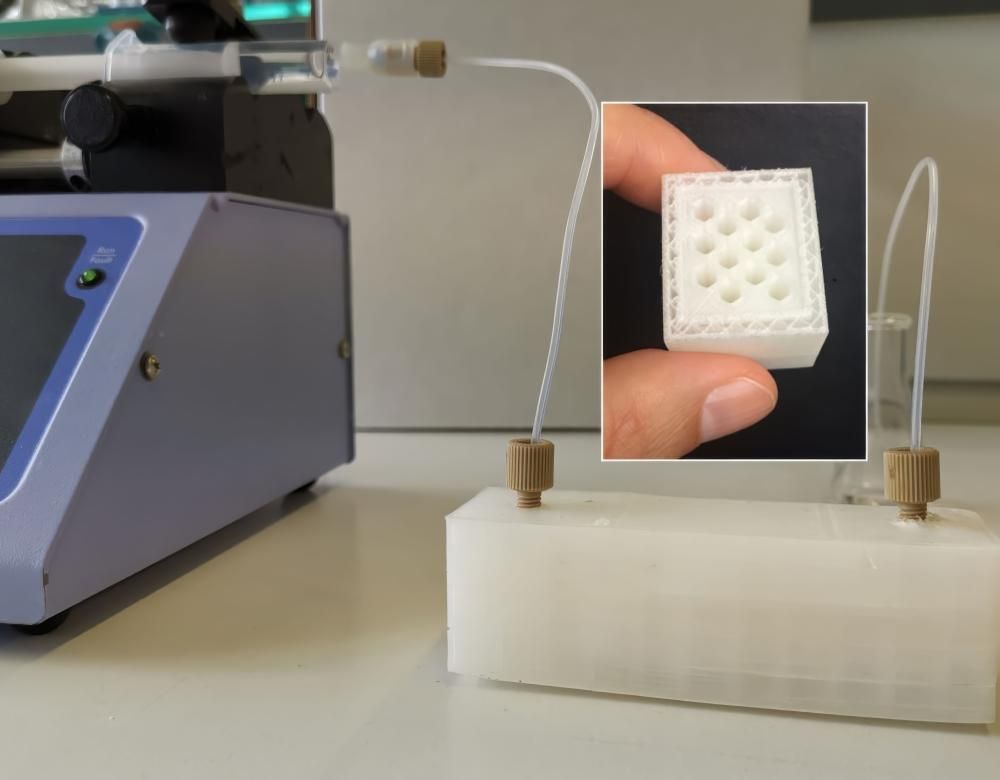

Biology, biochemistry and nuclear physics: the applied sciences have tackled the subject of the attacks via development of new materials, tracking systems and protective tools useful to counterterrorism. For example, three French teams of chemists worked on neutralisation of chemical weapons by using a safe, simple and easily transportable procedure (photo). Another example: after studying the interactions of a neurotoxic substance with various materials, a physics-chemistry laboratory ended up developing a biosensor able to detect pesticides.

Radicalisation, a subject in the shape of a challenge

2018 saw the publication of the book “The Radical Temptation. Survey among High School Students”, edited by two sociologists specialising in youth, Olivier Galland and Anne Muxel. The work involved, which began in 2015 following the CNRS’s call for projects, compiled the conclusions of a major survey conducted among 6,800 high school students on their relationship with radicalism. The main result highlighted is the existence of an “Islam effect”, in other words, young Muslims’ greater sensitivity to radical and absolutist ideas. The book was well received by the press but was fiercely criticised by the scientific community, which pointed fingers at its hazy definition of radicalism, biased methodology and a questionable theoretical framework. The controversy surrounding the survey, which was nonetheless conducted in good faith by its authors, highlighted the importance of adopting a rigorous scientific approach, above all when addressing subjects responsible for strong political tensions.

Radicalism is one of the main subjects of a study submitted in the context of the 2015 call for projects. Most of the work was carried out on the ground, opening up interesting discussions on the political, historical, psychological and social conditions leading to radicalisation. Several investigations were carried out in prisons while others analysed narratives of exiled and migrant populations and far right radicalisms. In order to facilitate work on such a sensitive subject, Cosprad (Scientific Council on Radicalisation Processes), created in May 2017, brings together researchers and representatives of the Ministry of the Interior.

The words of the attacks

Words can be analysed using statistical tools. The literature researcher Charlotte Lacoste (University of Lorraine) focused on the data collected in phase 1 of the 1000 Study: 934 interviews, 1,431 hours of filmed testimonies, 40,000 pages of transcripts and 14 million words. By doing so, she revealed a gendered division of discourse: a lexical field of emotions among the women and a more factual, analytic posture among the men. Analysis of the 1,325 messages in the 11th arrondissement’s condolence register showed that its inhabitants employed a vocabulary similar to that of direct victims – a sign of the impact the attacks had.

The role of victims’ associations

Victims’ associations are created by and for the people concerned with a view to providing a space for caregiving, listening and mutual support after traumatic events. Life for Paris, 13onze15 Fraternité Vérité have provided invaluable help in disseminating calls for participation in scientific studies, doing so on behalf of the extensive 13 November Programme and Guillaume Dezecache’s study in social psychology based on the testimonies of 32 Bataclan survivors. For the last eight years, the AfVT, which brings together victims of all terrorist attacks, has on another hand facilitated a radicalisation prevention scheme based on exchanges between high school students and victims.

Science at the service of society and vice-versa?

The flexibility and rapidity of the CNRS’s call enabled the funding of works running from short targeted studies to preliminary investigations leading to large-scale projects. As a result, science was put fully at the service of society and had to adapt by taking on the subject in crosscutting fashion. Projects focusing on the attacks often went beyond their intended purpose, enabling unprecedented and lasting collaborations, as in the case of the 13 November Programme.

In addition, much of the work carried out has had an impact outside the academic world: mentions in the press, talks at schools, books, roundtables and podcasts. With ten years of hindsight and despite a few reservations, Alain Fuchs gamble seems to have paid off: dissect the attack phenomenon so as to better understand it, prevent it and, ultimately, try to better handle its consequences.

Shortly after the attacks, the “sociological excuses” controversy started by Manuel Valls, who was Prime Minister at the time, is indicative of politicians’ possible mistrust of the humanities and social sciences, which are nonetheless essential to proper understanding of the world. His assertion that “to explain is already wanting to excuse a little” caused an uproar in the scientific community, which firmly upheld the essential exercise of analysis.

In spite of everything, major research projects on terrorism have been carried out successfully, including the 13 November Programme and other initiatives launched under the aegis of the CNRS, eager to build bridges between scientists and policymakers.