An ageing population

A falling birth rate and rising life expectancy: the proportion of older people is constantly increasing. What are the consequences?

by Kassiopée Toscas - Published on

Why ageing?

The world’s population is ageing as a result of the combined effect of declining mortality and lower birth rates. As a result, by 2100, 1 in 4 human beings will be over 65.

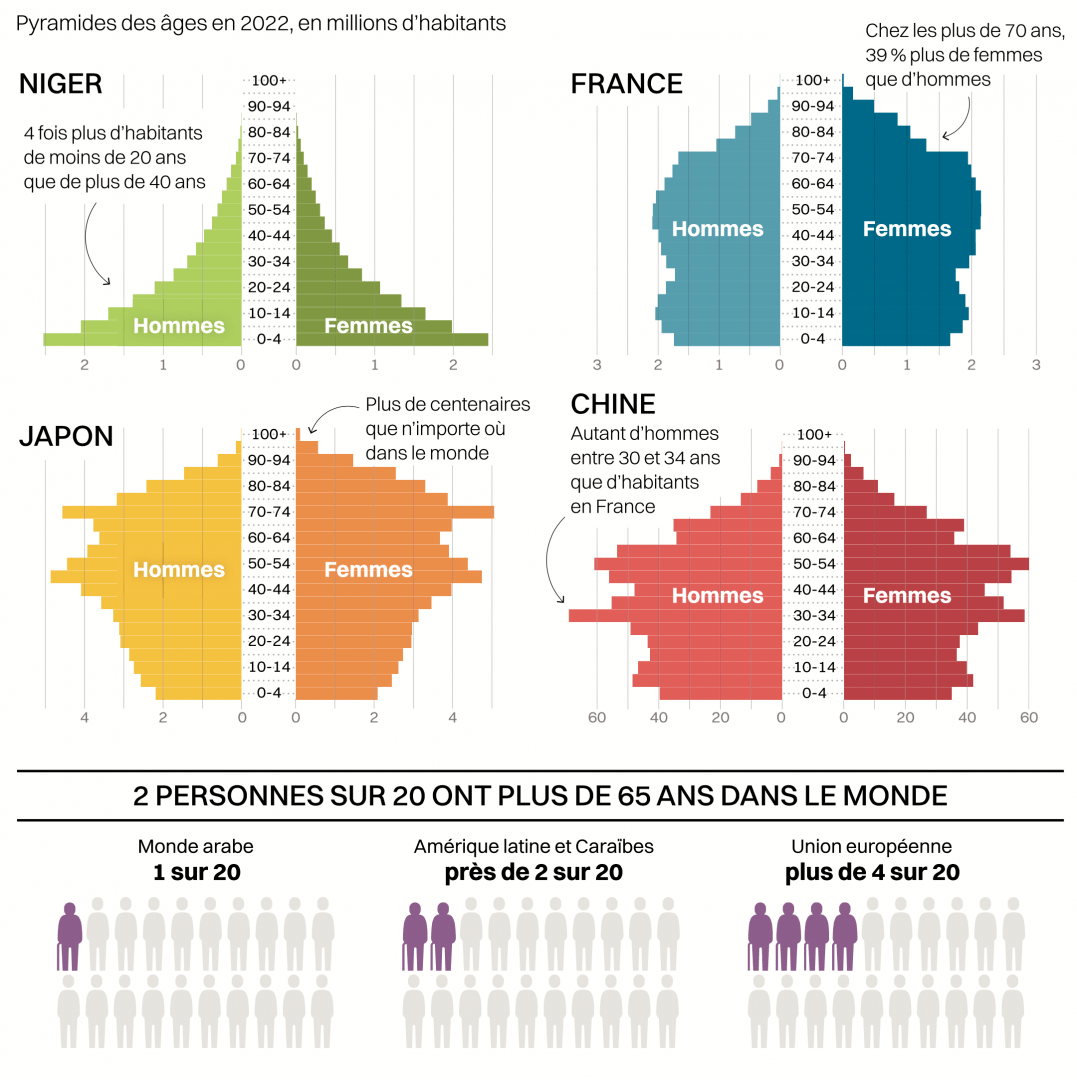

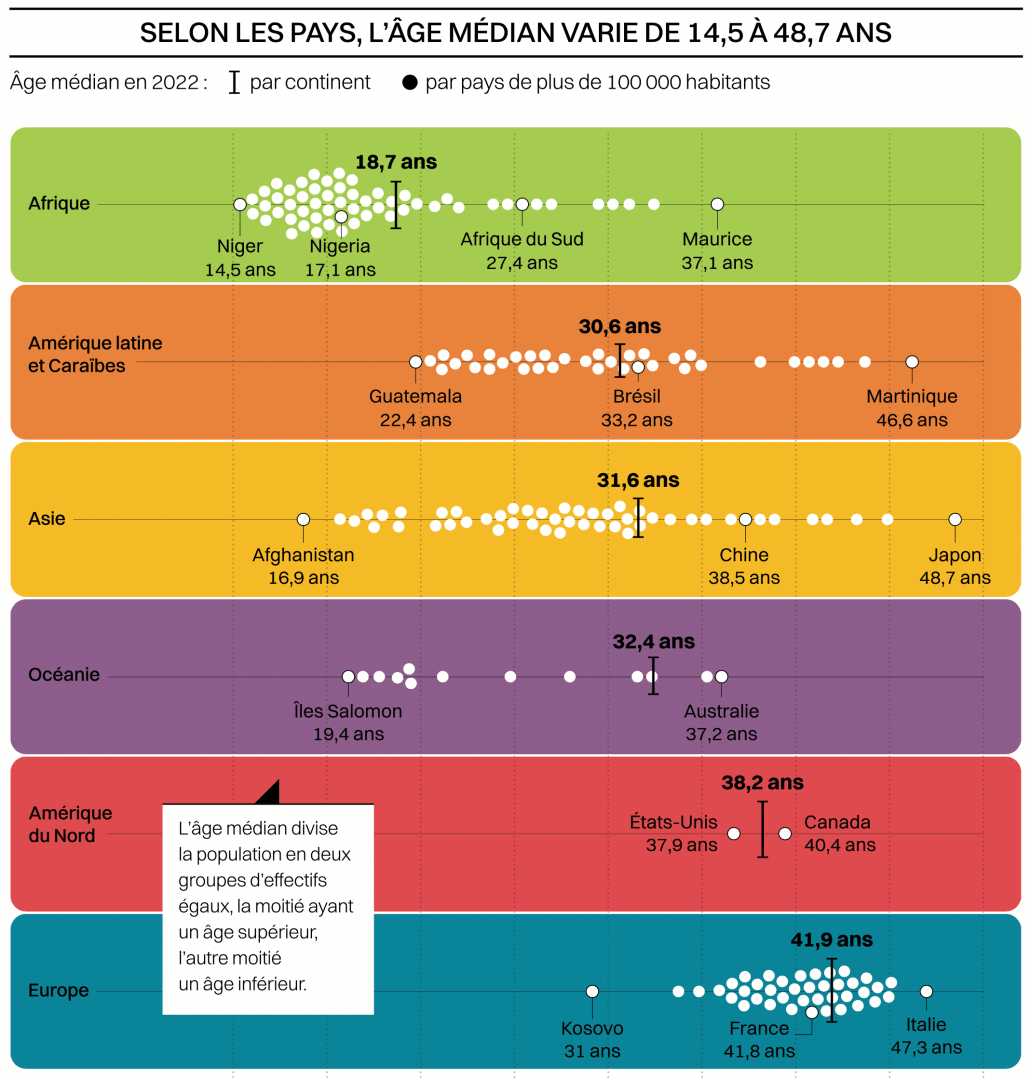

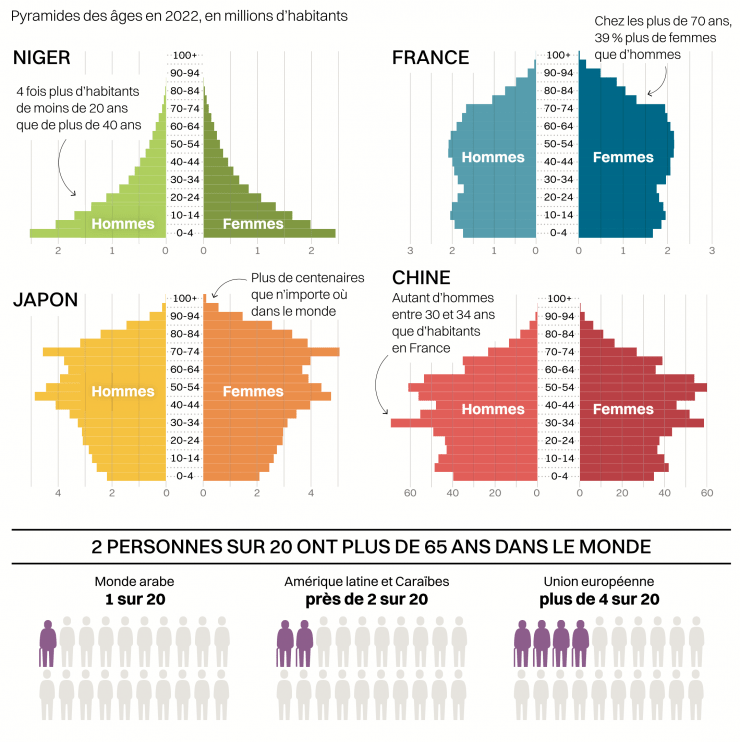

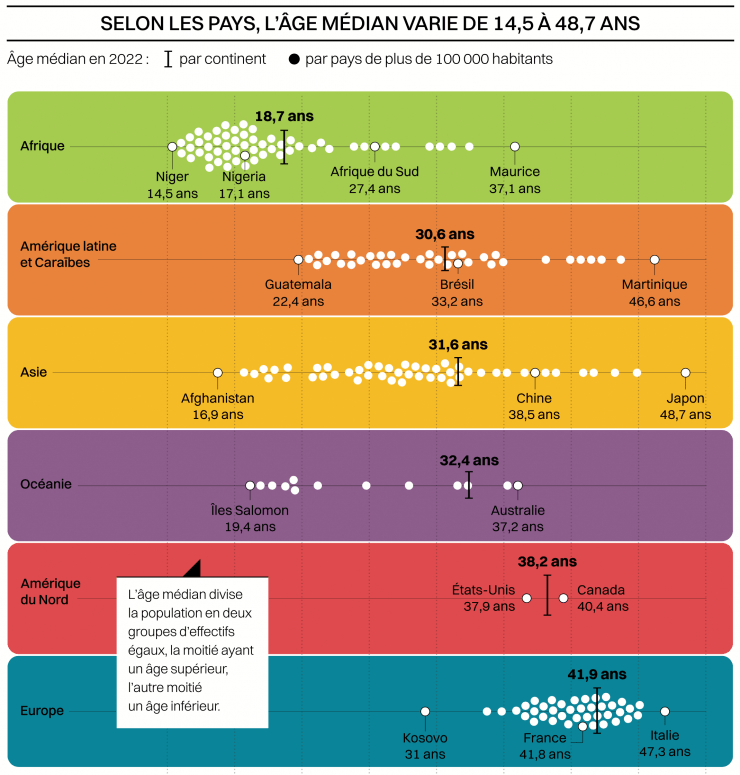

While 1 in 20 people in the world were over 65 in 1950, the proportion has now doubled to 1 in 10. And it will be nearly one in 6 by 2050, according to the latest UN forecasts. This is the inexorable continuation of the demographic transition that began two centuries ago in Western Europe with economic, social and health development and the modernisation of lifestyles. On the one hand, mortality continues to decline, including at older ages, so that global life expectancy at birth, which was 64 in 1990, reached almost 73 in 2019 and is expected to exceed 77 in 2050. On the other hand, fertility is declining as infant mortality declines and family aspirations change. As a result, two-thirds of the world’s population now live in a country where fertility is below 2.1 children per woman, the replacement level. And while fertility remains high in countries that have not yet completed their demographic transition, they are all following the same trajectory, albeit with different timetables and rates. The evolution of the world median age—which divides the population into two equal groups, here schematically “young” and “old”—sums up the situation: from 24 in 1990, it is now 31 and is expected to reach 42 in 2100, according to the UN. By that time, the global ratio between young and old will be reversed: those under 20 will represent only 22% of the world total, compared with 33% today. Meanwhile, the over-65s will account for 24% of the world’s population in 2100, compared with 10% today.

Birth policies with little effect

Faced with a rapidly ageing population, the Chinese government abolished the one-child policy in 2015 and has since sought to boost the birth rate, authorising up to three children per family since 2021. A 180° turn, with no effect for the moment, as Chinese fertility has never been so low - 1.2 children per woman in 2022. The reason: when education progresses and living conditions improve, in China as elsewhere, fertility drops because families want to have fewer children. Today’s world fertility rate is 2.3 children per woman, and is expected to decline to 2.1 by 2050 and 1.8 by 2100.

Accelerated ageing in the south

Developing countries, which began their demographic transition later, will face very rapid ageing.

Because of economic growth and access to medical progress in developed countries, the countries of the south have seen—or will see—their infant mortality and fertility rates fall very rapidly. North African countries, Iran, Syria, Vietnam and Brazil will thus experience accelerated ageing. While it took France 114 years for the proportion of people over 65 to double in its population, and 71 years in the United States, it took Thailand 22 and Tunisia 20 years to experience the same trend. 10 Sub-Saharan Africa will age later, in the second half of the century. With a fertility rate of 4.2 children per woman on average, its population remains very young, with the proportion of people over 65 varying from 2% to 5%. Whether it is in the making or underway, this sudden ageing will be a major challenge in the countries of the South, where the elderly have long been left out of public policies. Health services are not adapted: in sub-Saharan Africa, access to care is difficult—gerontology services are non-existent or limited to the capital cities—and the pathologies of old age are poorly addressed or not treated at all. As for social protection, while some countries, like Brazil, have an embryonic pension system, no developing country has a general system. Not to mention the fact that family solidarity, which used to provide care for the elderly, is gradually being eroded with the modernisation of lifestyles and the emigration of young people. The countries of the South therefore face a major challenge.

Country-specific ageing

The inequalities of ageing

We are not equal in the face of ageing: rich and poor, men and women, are not exposed to the same risks.

Unsurprisingly, life expectancy varies according to the socio-professional category. In France, a 35- year-old man can expect to live another 47 years if he is a manager, and only 41 years if he is a worker. The gap is 13 years between the richest 5% and the poorest 5%. Male and female workers therefore live shorter lives, but also longer in poor health. This is due to overexposure to serious illnesses (cancers, cardiovascular diseases, etc.) and disabling illnesses (musculoskeletal and anxiety disorders); poorer living conditions, access to and use of health care; and more frequent risky practices (alcohol, smoking, etc.). Women live longer than men (85.6 years compared to 79.7 years in 2019 in France), but with proportionally more years of dependence. The link between family and professional life exposes them to greater precariousness, with interrupted careers, and to anxiety or depressive syndromes. However, men are gradually abandoning risky behaviour. Meanwhile, recent female generations are more exposed to cardiovascular and cancerous diseases (smoking, sedentary lifestyle, etc.). At present, life expectancy between the sexes is therefore tending to converge. The gap would be only three years in 2070 (93 years of life expectancy with women, 90.1 years for men), compared with six years today, according to INSEE forecasts.

Living to a ripe old age, but in what state of health?

Some of the years of life “gained” are accompanied by functional or disabling limitations (mobility, memory, sight, hearing, etc.). But the years of dependence should remain stable, at around 3 to 5 years of total life expectancy, because health policies will make it possible to more effectively identify and prevent loss of independence. As for neurodegenerative diseases, they will undoubtedly be more visible since there will be more very old people, but their prevalence may decrease. This is already the case with Alzheimer’s disease, which has been declining for 20 years in several countries thanks to higher levels of education and the fight against vascular risk factors.

Life expectancy is still increasing

Life expectancy continues to rise as a result of major advances in healthcare, but at a slower pace, and unevenly across countries.

In 2019, life expectancy in Africa averaged 63, compared with 79 in Europe. Its evolution is the result of successive waves of progress, or “health transitions”, which follow different timetables around the world. The first is the fight against infectious diseases, which began in Europe at the end of the 18th century and spread to the rest of the world. However, this transition is not complete in countries with fragile economies, such as sub-Saharan Africa, which was hit hard by AIDS. The industrial countries then learned to manage cardiovascular diseases and then the so-called “societal“ diseases: violent deaths, smoking- and alcohol-related illnesses, etc., with sometimes uncertain success, since in the United States the opiate pandemic and obesity have caused male life expectancy to fall since 2014. Finally, some developed countries, such as France and Japan, are now taking action to combat the pathologies of old age. Beyond a certain age, of course, life expectancy increases less rapidly. But gains are still expected in the fight against cancer (screening and treatment) and neurodegenerative diseases (health policies and innovations): a life expectancy of 100 years is not out of reach. The countries of the South, for their part, will undoubtedly have to make these different transitions simultaneously.

Will everyone be old tomorrow?

Social issues to be anticipated

Societies will have to adapt to the new balance between generations, with a growing number of elderly and often dependent people.

In France, the proportion of people aged over 85 will almost double by 2050, rising from 3.5% to almost 7% of the total population. This will have consequences for the health system, housing, social ties, etc., and in the long term will undoubtedly lead to profound social reorganisation. To cope with the growing number of dependent people, there are several avenues to explore: improving prevention and eradicating or limiting the pathologies of old age by supporting research—which is highly active on neurodegenerative diseases. In addition, adapting the domestic environment can compensate for functional limitations and thus delay the loss of autonomy: development of home automation; facilitating mobility through safe paths, the installation of benches, etc. But it will also be necessary to upgrade the jobs of assistance to the elderly and to rethink the possible end of life, so that the choice is not limited to an alternative between a nursing home and home help: solutions for intermediate housing, for example, would make it possible to pool services. And of course, we need to rethink social protection systems: develop dependency insurance, adapt the contributory pension system, etc. At present, 20% of the costs of independent living assistance are borne by families, with the rest covered by the community, compared with 8% in health expenditure.

New intergenerational solidarity

Intergenerational exchanges could increase within families. Children and grandchildren would take care of their parents or grandparents who have become dependent; the latter would participate in the life of the household in the form of financial support, housing, help with childcare, etc. As inheritance comes later, monetary transfers prior to the death of the ascendants would also make it possible to help young adults. On the whole, intergenerational solidarity will undoubtedly have to be rethought, with greater proximity between close generations, who benefit from exchanging, rather than between the very young and the very old.

Disrupted life paths

A longer life disrupts life paths; this is a phenomenon that has already begun. The average age at which people receive an inheritance is now over 50, according to INSEE. Although still rare, late separations are on the increase, sometimes heralding new relationships: in 2016, according to INED, divorces of people over 60 represented 12% of all divorces for men (8% for women), compared with only 3% to 4% twenty years earlier. In short, representations will also have to change: there is not one way of ageing, but many.

The fantasy of extinction

Will the decline in births lead to the extinction of the human species? The answer depends on the data chosen at the outset. Assuming that the whole world is subject to the current European fertility rate and life expectancy (1.5 children per woman and 80 years) and maintains this indefinitely, the world population would be divided by 10 every 200 years, falling to 1 billion in 2,250 and . . . 100 people in 3,650! But this is a theoretical scenario and purely demographic extinction seems unlikely. If there is a risk, it lies rather with climate change, the erosion of biodiversity and the depletion of resources.