Satellites: solutions in the sky

African development also requires the use of satellite data for resource management, territorial development, etc. There are more and more applications. Follow the guide.

An investigation by Amal Benotman, Boursier Tchibinda, Désiré Ouedraogo, Jean-Christian Nselel, Ramatoulaye Moussa Mazou, Tobias Carlos and Vincent Namrona, coordinated by Sébastien Hervieu - Published on

On 22 March 2021, Tunisia launched its first experimental, 100%-homemade satellite into space: Challenge One. It was the sixth African nation to build its own satellite. Five others had already designed theirs with the help of foreign constructors, so a total of 11 countries out of 54 now have satellites. Over the last few years, space-technology development has gathered pace on the African continent. Not with the aim of conquering space – not yet – but to enjoy all the benefits of satellite data. With access made easier, scientists, engineers and even ordinary citizens can use such data. And their priority is to identify solutions to overcome obstacles to African development. So Challenge One will collect data from thermometers and sensors that measure pollution and humidity. Why? To provide that precious information in real time, even for areas of land with no Internet coverage. Very useful on a continent where only a third of the inhabitants have access to the Net!

Satellite data: a source of development

More and more African countries are seeking to use information collected from space for a huge variety of applications.

For twenty years or so, Africa has increasingly been using satellite data to speed up its development. Reflecting this dynamic effort, fourteen African countries now have their own space agencies. The processing of information gathered by African or (more frequently) foreign satellites assists resource management, territorial development and the fight against climate change. There are more and more projects – for instance in Zambia, where the mapping of water resources enables rural communities to manage their reserves more efficiently, or in Nigeria, where the interpretation of satellite images facilitates the tracking of Boko Haram jihadis. Authorities need reliable, regularly updated indicators, for instance to optimise their handling of the rapid urbanisation of the continent. Yet obstacles remain. Although the ‘entry fee’ has come down with the introduction of nanosatellites (satellites weighing less than 10 kg), many African countries do not yet have enough money to invest in the sector. And there is still only limited expertise available, whether for the construction of satellites or to make use of the data collected. But across the continent, more and more universities are offering specific courses to train students, politicians and development-project managers in how to use data when making public decisions.

Forecasting the arrival of migratory locusts

Locusts are seen as the most destructive migratory pest in the world. Swarms of several billion hardy insects devour crops in East Africa. To limit the damage, a Kenyan company has launched the Kuzi application, based on artificial intelligence and automated learning. Using data collected by satellites and sensors on the ground (humidity, wind, etc.), it can predict where locusts will breed, the formation of their swarms and their migratory paths. Farmers can receive alert messages – in English or the local language – up to three months before a locust invasion. The application is available in Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia and Somalia.

Precision agriculture on its way

Farming generates a third of the African continent’s GDP, but yields remain low. So local start-ups are developing tools for ‘precision agriculture’: real-time monitoring of crop health using data collected by satellites, drones and sensors on the ground, and their processing using artificial-intelligence techniques to produce forecasts and recommendations. Founded in 2017, the Côte d’Ivoire start-up WeFly Agri markets maps of crops, phytosanitary diagnoses and aerial crop-spraying done by drones built using 3D printers.

Looking after cattle

In Mali and Madagascar, new tools are helping stockbreeders take their herds to better pastures.

In Sahel, nomadic stockbreeders are less and less able to rely on their traditional knowledge to lead their herds to better pastures and sources of water. That is because of climate change and the risk of jihadi attacks. But a mobile-phone application, Garbal, has been developed to assist the herders. Launched in Mali in 2017 and then extended to Burkina Faso, it gives direct access to valuable information, such as the location of water sources, cattle markets and veterinary stations, and data on rainfall. Collected by satellite, the data allow breeders to save time and improve their herds’ productivity. Messages are sent in French and local languages. In 2019, on the other side of the continent, a team of Madagascan researchers developed mapping software to identify places where the most feed is available for cattle. Named 3C-BIOVIS, it combines agronomic data measured on the ground with vegetation indicators (NDVI), such as the brightness of green plants. The information is supplied by satellite images that show the state of pastures at a given time. On the Great Island, the zebu is the main source of protein for the mostly poor population. 85% of its inhabitants live in rural districts. 3C-BIOVIS makes it possible to identify how many animals can graze in a given area.

Counting elephants from space

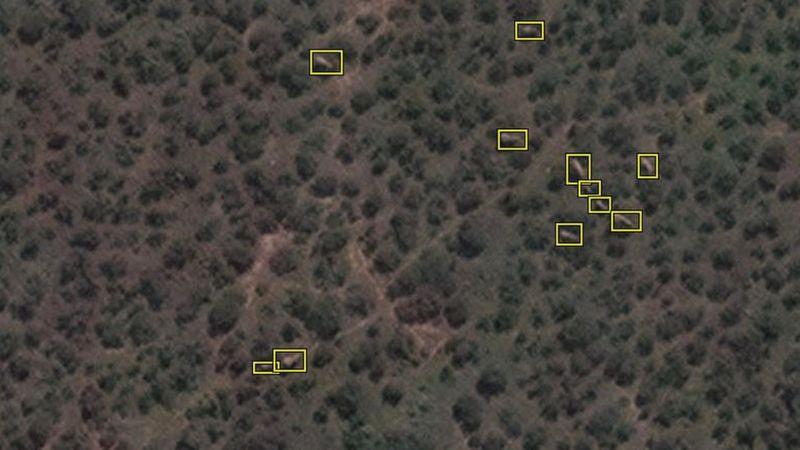

To protect elephants, we must know where they are. Using an algorithm, a satellite can now locate and count the pachyderms.

Grey patches in a forest of green patches. Taken by a satellite in orbit 600 kilometres above the Earth, the picture shows elephants moving among the trees and bushes of the South-African Addo Elephant National Park reserve. In a study published in December 2020, researchers from the British universities of Oxford and Bath listed the advantages of satellite imaging for counting elephants. Until now, the most common technique was to use an aircraft flying over the area. But that is a time-consuming and sometimes inaccurate solution. Whereas an observation satellite can, depending on the weather, examine up to 5,000 square kilometres in one pass and then send back the data in just a few minutes. So scientists have taught an algorithm to identify pachyderms – adult and young – against different backgrounds. There is no risk of this non-invasive technique disturbing the animals and it can be used everywhere, even in hard-to-reach or dangerous areas. Counting elephants and knowing exactly where they are is vital for their protection. Poaching and loss of habitat due to human activities have slashed elephant populations from millions at the start of the 20th century to barely 400,000 today.

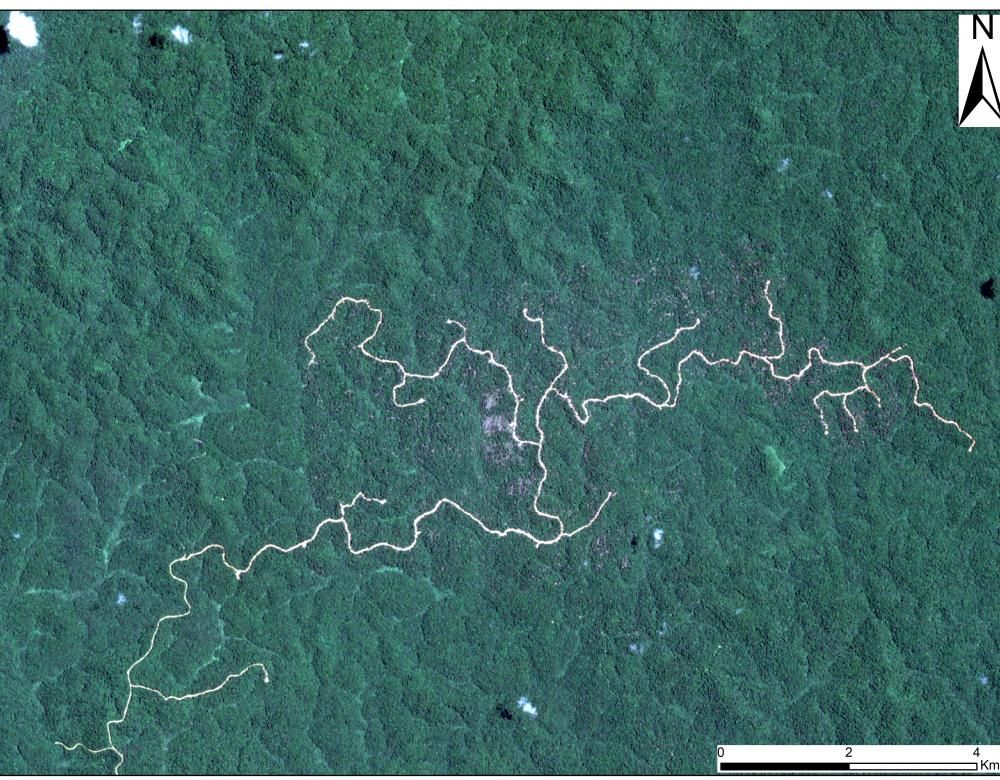

Monitoring the forests of Gabon

Forests cover 88% of Gabon. In 2018, a System for the Observation of Natural Resources and Forests (SNORNF) was set up to protect them. It receives satellite data from the Gabon space agency which show the state of forest cover almost in real time and detect illegal logging activity. It also maps protected areas and those devoted to mining and farming. Finally, using combined data from remote sensing and observation in the field, the SNORNF assesses flows and reserves of carbon in the forests, so contributing to the effective management of Gabon’s carbon footprint.

71 dead, 33,000 homes destroyed and more than 350,000 disaster victims. At the end of August 2020, Niger experienced its worst flooding in a century. Built on the River Niger, the capital, Niamey, home to more than a million inhabitants, suffered catastrophic damage. In this Sahelian country where nearly 40% of the population live in extreme poverty, there is frequent flooding during the rainy season. So why did the river burst its banks on this occasion? Because of chaotic urban planning and climate change, which had led to heavier rainfall. To tackle the floods, Ousmane Seidou, a Nigerien hydrologist, has developed a ‘made in Niger’ alert programme. The application collects satellite data on predicted precipitation in the catchment area, as well as information on water levels observed by stations located upstream on the river. The data are analysed to generate simulations of flood risks over five days. When the risk becomes high, the application automatically sends text messages and emails to the authorities responsible for triggering special measures. Ousmane Seidou’s system helped to forecast last year’s floods, especially predicting that the main dyke in Niamey – which protected homes, drinking-water wells and fields – would give way, despite having recently been raised to a height of 6.5 m. This made it possible to evacuate part of the population in time.

More and more African satellites

Forty or so African satellites are in orbit today. A booming industry.

In 1998, Egypt became the first African country to launch a satellite into space. Since then, ten other countries have followed in its footsteps: Algeria, Angola, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa and Sudan. In all, 41 African satellites have been placed in orbit. And the continent’s space development is accelerating: nearly half the devices were launched over the last five years. In 2017, Ghana pulled off a coup when it successfully put into Earth orbit the first satellite entirely built by an African nation. Sent to the International Space Station on an American SpaceX rocket, GhanaSat-1 is a miniature satellite designed by researchers at All Nations University in the city of Kofuridua. It is equipped with cameras to monitor the coastal areas of the West-African country.

The emergence of nanosatellites – which are obviously less expensive – has brought satellite technology within the reach of African nations and so increased their independence. They can now acquire their own data for telecommunications, meteorology, navigation, territorial surveillance and research. However, Africa continues to suffer from a lack of expertise in the domain and has no launch vehicle. The 2019 creation of the African Space Agency with its headquarters in Cairo will enable joint projects and closer cooperation between countries. The African space market should be worth more than 10 billion dollars (8.3 billion euros) by 2024.

Census-taking despite all the difficulties

20,487,979. That is the population of Burkina Faso according to the 5th preliminary census published in December 2020. Identifying that figure was a challenge: the danger of jihadi attacks prevented administrative officers from visiting a number of communities. So the National Institute for Statistics and Demography (INSD) turned to satellite images to identify the number of homes in remote places, using a grid technique to divide an area into identical squares. Knowing the distribution of populations is essential when deciding the locations of future dispensaries and schools.

Geolocated addresses in view

Start-ups are developing the home-delivery market using GPS geolocation.

The vast majority of Africans do not have a precise home address, so it is difficult to receive deliveries. To solve this problem, Senegal’s Bamba Lô devised ‘Paps’ in 2016. The bicycle and scooter delivery service is now available in a number of African countries. It works by geolocation. If a customer wants a pizza or medicine, they place an order via an application, which records the location of the customer using GPS. The algorithm then passes on the order to one of the 800 delivery riders in the database, choosing the closest one available. Initially developed in cities, the system is steadily being extended to villages. And since 2014, the Kenyan start-up Okhi has been providing addresses for people who do not have one. It asks for a photo of the front door or gate of the person’s home and links it to geolocation coordinates by GPS. The customer is then registered in the Okhi system and has an address. They can use it for any purpose – administrative, banking, etc. But having an address does not always enable people to receive deliveries. You also need to be near a road and 60% of Africans live more than two kilometres from a surfaced track. Drones might be the answer. In Rwanda and Ghana, the American start-up Zipline already uses them to deliver blood bags to hospitals or Covid-test samples to laboratories.

Visions of Africa

A special issue by LeBlob.fr

Investigations

- Satellites: solutions from the sky

- Greening Africa again: a challenge to be met

- Medicine 2.0: a chance for Africa?

- Orality in the digital age

Videos

- The pharmacist who treats malaria

- The engineer who makes his city smarter

- The astronomer who observes the stars in love

- The biochemist who heals soils

- The agronomist who plants crops and trees together

- The biologist who chases away sleeping sickness

- The statistician who tracks HIV

- The nutritionist who keeps an eye on groundnuts